Just because I mistook cartoonist Alison Bechdel’s 1990s appropriation of Norman Rockwell’s The Gossips — the Americana illustrator’s late 1940s painting that depicts a dozen sets of trash-talking heads — as her invention doesn’t mean that the original is not an example of comics. I first saw Bechdel’s version in catalogues for the merchandise she made and sold to fans of her strip about the lives and loves of a mostly lesbian community, Dykes to Watch Out For. When I saw a similar image on the cover of the Comics Journal in 2003, that time roping in comics characters from a panoply of classic American newspaper strips, I figured its artist, R.K. Sikoryak, was quoting Bechdel.

Atlanta artist Fabian Williams’s oil painting Gossip, on view as part of his solo show “Rockingwell,” at the Rialto Center for the Arts through June 19, brings this homage tour full circle in several ways. The obvious one is medium, since Rockwell rendered The Gossips in oils. The less obvious echo is that both artists employed models they knew — neighbors for Rockwell, fellow artists for Williams. I don’t know whether Williams worked from photographs of his models for Gossip (though it seems likely), but Rockwell famously did so for its precursor. The adjacent grid of photos visible in a Gossips installation image from the Norman Rockwell Museum illuminates the invisible panel progression of the original painting, an effect Williams duplicates superbly. Considered alongside Rockwell’s own view of himself as a “story teller” and what strikes me as a perfectly sound definition of comics — static, sequential pictures as narrative — both The Gossips and Gossip are comics. Such taxonomy matters merely because the most successful works in Williams’s show are his sequential picture narratives.

Although Williams’s exhibition title honors his art-world hero, another 20th-century figure many readers might not associate with comics also exerts an influence over multiple works in “Rockingwell”: Rube Goldberg. Perhaps because of an eponymous and ongoing series of so-called Machine Contests, his name’s strongest modern association is with actual but unlikely three-dimensional contraptions, despite his Pulitzer for cartooning and the use of his given name, Reuben, by the National Cartoonists Society for its own annual awards.

Williams uses the term contraptions to label a series of bluntly political drawings and watercolors whose format makes them kin to both the comic strip and the editorial cartoon. Unlike Gossip and its unseen dividers, Williams’s Contraptions use mathematical symbols to chart some intractable aspects of modern life in the United States. Easily the most controversial of works in this series addresses Chris Kyle, the subject of American Sniper. Penciled portraits of Kyle — one living, one dead — bracket a sharpshooter’s rifle and a pile of bodies. The work’s title, alas, misspells Kyle’s first name, but the artist’s point about American means and ends applies nonetheless: Kris Kyle x lethal power / 255 confirmed kills = American karma. Another posits equivalencies between Jihadi John, Al-Shabaab, the fictitious G.I. Joe adversary Cobra, and the Department of Homeland Security’s seemingly endless need for funding (and for new foes).

Williams’s pencil renderings are sublime. They blur a line between precise portraiture and savage caricature. I suspect the distortion of hands that recurs throughout this exhibition might be as much a tactic for focusing attention as for being up front about a part of human anatomy that troubles many a representational artist. I’ll save my support for that claim till we get back to oil paintings, though. With one exception (which I’ll save for last, the way I saw it in viewing “Rockingwell”), I found Williams’s watercolor entries in the Contraptions series slightly less successful, a bit less alive, facially speaking.

The artist uses such disturbing vacancy as an advantage in his pencil portrayal of former Arkansas governor Mike Huckabee, whose eyes in Williams’s rendering evoke Gollum in soothing contemplation of The Precious. This exhibition’s seeming bit of cleromancy manifests in a framed, matted, and mildewed set of pencil portraits collectively labeled The Bush Administration. As Williams explained in his artist talk, the work was one of several that got flood-kissed during basement storage. Only the renditions of George W. Bush and Dick Cheney, as well as one depicting John McCain, got moldy, though. A frame holding several Democrats’ portraits escaped the event with mere water damage.

Upstairs, on the Rialto’s mezzanine, are items from Williams’s RaceCard series. The ace among these playing-card-based works depicts Jesse Jackson and Al Sharpton, whose hands are key. Sharpton points “overhead” with an extended index finger — the eureka gesture … except here, because he and Jackson share a torso as face cards do, that finger aims at the floor. Jackson, upright when I saw the painting (some of the RaceCard canvases are mounted on armatures that let their paired subjects take turns being on top), has an ominous gray tinge on his left palm and on that side of his face, too, as if he has transferred some palpable dismay from hand to head. Sharing a slightly less crisp work titled The White RaceCard are Bill O’Reilly and Rush Limbaugh. Here, O’Reilly points at the viewer with a finger whose first joint is covered in blood red.

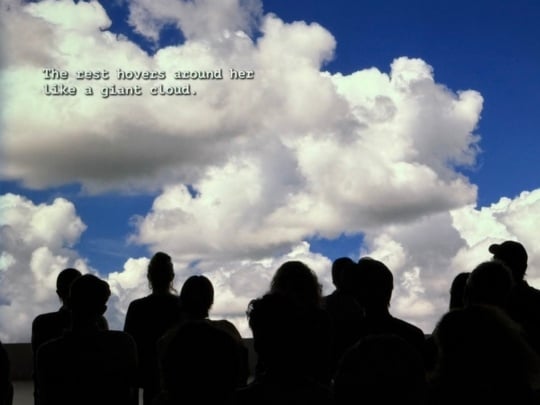

In Gossip, many of Williams’s rumormongers point at themselves or each other. They could be doing so in meta-awe of their various renderings, given the life their creator bestows upon them with mere brush and paint. Only as I left the Rialto lobby did I find the promotional postcard for “Rockingwell,” which appears to reproduce a study (possibly in watercolors) for the show’s main canvas. The differences between the two versions are subtle, fascinating, and fraught — much like this flawed but powerfully promising show overall.

Fabian Williams, “Rockingwell,” is on view at the Rialto Center for the Arts through June 19. We suggest calling in advance to ensure access.

Alabama escapee Ed Hall writes journalism, poetry, and fiction. His work has appeared in Newsweek, the Atlanta Journal-Constitution, Code Z: Black Visual Culture Now, and the Dictionary of Literary Biography.