In the introduction to the first book in his 20-volume photographic study, The North American Indian, Edward S. Curtis wrote that the objective of the work was to document “a people who are rapidly losing the traces of their aboriginal character and who are destined ultimately to become assimilated with ‘the superior race.’” This was well over a century ago and extinction, more than assimilation, has proved to be the bigger threat to Native American life and culture. For most of us, this is a part of our history that we still know little about, and in “Unearthed: A Photographic Search for Native American History through the Landscape,” Emily J. Gómez documents her own attempts to uncover and understand the past using landscape as a commentary on what is missing in the frame or as a clue to a deeper meaning within it.

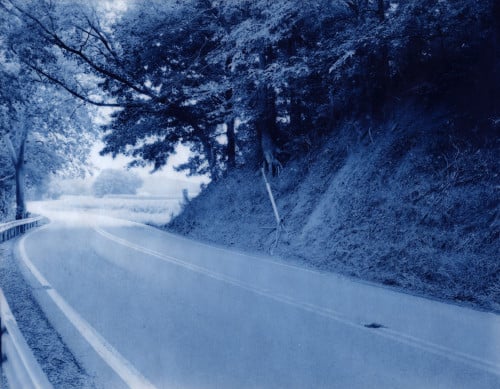

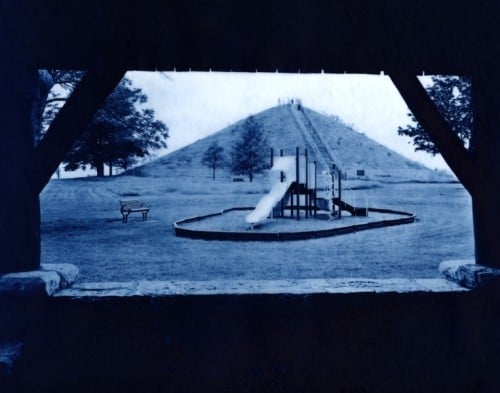

The first thing you notice is the formal beauty of her photographs. Shot by Gómez on an 8-by-10 Deardorff camera, the black-and-white images have been printed as cyanotypes on Wyndstone Vellum, which give the images a smoky blue tint. This treatment sets an elegiac tone for the exhibition but also transforms several settings that might look prosaic in a standard black-and-white format into something mystical and ethereal. Yet upon closer inspection, the landscapes also bear silent witness to what we have lost since President Andrew Jackson’s Indian Removal Act of 1830.

In many of the photographs, Native American sites that were once places for religious worship or burial grounds or thriving communities are now obscured or forgotten in locations where office buildings, paved roads, parks, and picnic areas have become the dominant feature. Miamisburg Mound, Miamisburg, Ohio – 2011, for example, depicts a perfectly manicured grass lawn in the foreground containing a park bench and a circular play area for children, complete with a slide and monkey bars. In the background, we can glimpse the Miamisburg Mound, which is believed to be from the Adena culture that existed from 1000 to 200 BCE in Ohio, Kentucky, and other locations. What was once a deeply spiritual place for the region’s original inhabitants has been relegated to backdrop, overshadowed by a family fun zone, a symbolic representation of the ongoing disenfranchisement of Native Americans.

Keowee Town, Salem, South Carolina – 2006, on the other hand, is more deceptive at first glance, and comes across as an atmospheric nature study that captures the early morning mist rising from a lake with the first rays of dawn. The real subject of the photo, however, is one you can’t see but is revealed in Gómez’s caption. Keowee Town, the former capital of the lower Cherokee Nation, lies below Lake Keowee, which was formed in 1971 by the Duke Power Company to generate hydroelectric power for the region. Gómez told me: “The photograph was taken from the site of the boat launch, and I don’t think the average person would know that they are driving their motorboat over a former Indian town.”

There are many ways Gómez could have approached this subject matter, but her subtle and contemplative treatment has a lasting resonance which might not have been the case had she presented “Unearthed” as a more confrontational critique of our genocidal past. And while several of the photographs feature bitterly ironic details in the composition, she avoids exploiting this aspect for dramatic effect with the possible exception of one unforgettable image that borders on the surreal—Gnadenhutten Cemetery, Gnadenhutten, Ohio – 2005. In this photo, we see a plain, wooden structure with the sign “Museum” in the background and a stand-in with facial cutouts in the foreground so that visitors can enjoy a playful photo op, a detail that becomes more mindboggling when you realize that 90 Christian Delaware Indians were massacred on this spot by Pennsylvania militiamen in 1782.

In her exhibition statement for “Unearthed,” Gómez, who teaches at Georgia College in Milledgeville, explains that her original vision for these photographs evolved from “capturing the essence of mysterious ancient monuments” to a more specific goal of creating “a visual memorial to the people who once lived throughout what is now the Southeastern and Midwestern United States. The photographs have also become a document of what we value as Americans as evidenced by the marks we make on our landscape through the things we build, preserve and destroy.”

I have not been aware of any other contemporary photographers who are engaged in raising the awareness of our vanishing aboriginal culture in this manner but Gómez mentioned to me that she recently discovered the work of Michael Sherwin, whose photographic series Vanishing Points was inspired by a 2,000-year-old sacred indigenous burial ground and village near his home in Morgantown, West Virginia. Gómez also cited Edward Steichen’s Pictorialist printing methods and Joel Sternfeld’s book of photographs, On This Site: Landscape in Memoriam, as important influences on her work.

“Unearthed,” however, is Gómez’s own personal take on the Indian Removal of the 20th-century and her aesthetic approach is seductive. “A photograph should be beautiful,” she stated. “I want people to be drawn in by the color and maybe by the form and the composition. Once they’ve let themselves into the photograph, I think they can start looking deeper into what it’s really about. That’s been my strategy.”

“Unearthed: A Photographic Search for Native American History through the Landscape” is on view at Georgia State University Ernest G. Welch School of Art & Design Gallery through July 31.

Jeff Stafford is an Atlanta-based art and lifestyle writer.