As 2017 drew to a close, Hollywood studios and independent film distributors raced to release their best movies in order to qualify for Oscar consideration. The documentary category in particular is unusually strong this year with such critically acclaimed contenders as JR & Agnes Varda’s Faces Places, Ai Weiwei’s Human Flow and Errol Morris’s The B-Side: Elsa Dorfman’s Portrait Photography. Not to be overlooked, however, are two remarkably diverse portraits of artists – Andres Veiel’s Beuys and Oren Jacoby’s Shadowman – which screened at the Virginia Film Festival in Charlottesville in November.

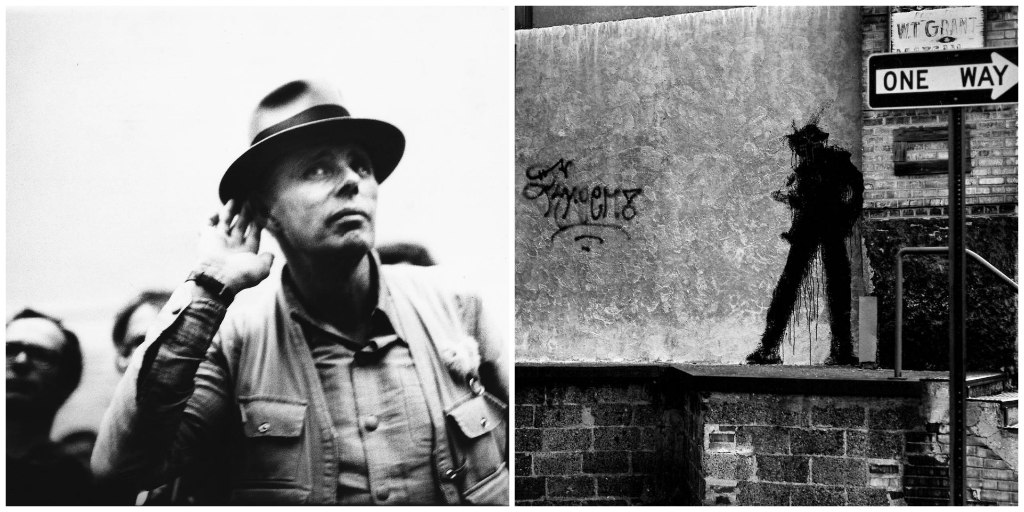

Neither documentary takes a formulaic chronological approach to their subject. Veiel’s film champions German artist Joseph Beuys as a radical provocateur who was associated with the Fluxus movement, while Jacoby’s Shadowman delves into the elusive figure of New York City street artist Richard Hambleton, who was famous before contemporaries Jean Michel Basquiat and Keith Harring but is the least known of the three today.

Beuys offers a complete immersion into pure, unadulterated Beuys, culled from rare live footage of his performance pieces, participatory happenings, debates with art critics and his charismatic interaction with students and fans. There is little about Beuys’s childhood or art training, however. His wife and two children are glimpsed but never properly introduced into the narrative, and most of his drawing, painting and sculpture of the late ’50s is glossed over in favor of what made him such a controversial figure in the German art world – and internationally – in the early ’60s. Although early critics of the film have complained that Veiel’s refusal to contextualize what he chose to focus on makes the film baffling to newcomers and frustrating for those familiar with Beuys, the documentary will be revelatory for anyone who wants to understand why Beuys is still considered important and influential today.

Veiel’s strategically curated footage supports most of Beuys’s more thought-provoking ideas and philosophies, such as the dictum that art should challenge the status quo to provoke social, political or environmental change, or that ritualized movement and sound presented as shamanistic or ephemeral performances can have a liberating effect on the artist and his audience. Beuys also preferred working with found or mass-produced objects and organic matter, which would later have an influence on Land art pioneers like Robert Smithson.

A psychological link between the artist’s frequent use of animal fat and felt and a traumatic, near-death experience during WWII is established toward the beginning of the film. Beuys always enjoyed blurring the line between fact and fiction and his version of the latter event has his plane being shot down over the Crimean Front in March 144 (he was a flier in the German Air Force) and him being rescued by a tribe of nomadic Tartars who treated his severe wounds by wrapping him in animal fat and felt. It is fascinating to see how these materials become recurring biographical themes in his work, from his dapper signature felt hat to key works like How to Explain Pictures to a Dead Hare (1965), Fat Corner (1968), and I Like America and America Likes Me (1974), a performance about the United States treatment of Native Americans for which he was wrapped in felt and transported on a stretcher to a room at New York’s René Block Gallery that he shared with a wild coyote for several days.

Veiel truly captures the essence and vitality of this artist who wore many hats: a mischievous prankster, an educator, a social activist (he helped found Germany’s Green Party) and a visionary who challenged staid ideas about art. You may come away wanting to know more about his life and work, and what could be a better recommendation than that?

Oren Jacoby’s Shadowman succeeds in the daunting task of rescuing from semi-obscurity the artist who was once called “the Godfather of NY Street Art.” Although Hambleton was usually characterized as a graffiti artist, he preferred the term public artist and his work influenced later street graffiti superstars like Banksy and the stencil artist Blek le Rat.

Originally from Vancouver, Hambleton moved to Manhattan’s Lower East Side in 1979, his aesthetic agenda already in place. Including extensive documentation from various video and film sources, photographs, media coverage and Jacoby’s own footage, Shadowman unfolds like a crime procedural drama beginning with Hambleton’s Image Mass Murder series from 1976-79. Making his mark on 15 major cities across the U.S., Hambleton startled, shocked and intrigued local residents with his faux murder scenes, which juxtaposed body outlines in chalk with red paint highlights in prominent public areas.

Hambleton followed this up with another multi-city tag campaign in 1980-81 known as I Only Have Eyes for You, for which he plastered street walls with hundreds of life-sized posters featuring himself as a stylish bon vivant with an unnerving, wide-eyed stare. But it was the Nightlife series he launched in NYC in 1982 that established his fame in the art world. Prowling the nocturnal streets of the Lower East Side, Hambleton would appropriate street corners, alleyways and other public wall spaces and, using black paint, create variations of a life-size silhouette that appeared to be watching the passing pedestrians.

Sometimes he would tag these figures with skull heads or crowns but eventually the Shadowman character would evolve into ink blot rodeo riders or cowboys resembling the Marlboro Man in a subversive urban twist on the famous icon. Then, at the height of his fame in 1984, Hambleton withdrew from the world, becoming a virtual recluse.

Jacoby’s film not only documents those heady days of early success but Hambleton’s lost years when he descended into heroin addiction, homelessness, erratic behavior and serious health issues such as advanced scoliosis and facial cancer that he attempted to hide under an increasingly large bandage. Yet through it all, his art remained his obsession. Even under the most desperate circumstances he produced the “Beautiful Paintings,” a remarkable body of work that contemplated natural landscapes in otherworldly colors and were a complete departure from his street art.

Despite an on-and-off relationship with Hambleton, Jacoby was able to document a lot from the artist’s final years, including a career resurgence in 2007-09 and then again in 2017. Jacoby states in his production notes, “Sometimes the experience of following Richard with a camera gave me a sense of what it must have been like to see Van Gogh in his fateful, final years as he was consumed by madness, addiction and his last burst of artistic passion.” The resulting film is a riveting portrait of creativity under constant, mostly self-inflicted duress.

“Beuys” is currently scheduled to appear at Film Forum in NYC (Jan. 17-30), the Honolulu Museum of Art (Feb. 15), Wexner Center for the Arts in Columbus, Ohio (Feb. 15), Parkway Theatre in Baltimore (Jan. 26-Feb. 1), and the Cleveland Museum of Art (March 20, 23).

“Shadowman” can be streamed on Amazon and iTunes and is available for purchase on DVD.

Jeff Stafford writes about art, film, music, gardening and other favorite topics for various digital publications.