Location: Nomadic in Miami, Florida

Founded by: Naomi Fisher and Hernan Bas

Operated by: Naomi Fisher and Lee Pivnik

Opened: 2004

Website: www.basfisherinvitational.com

Lee and Naomi responded to these questions on March 26, a few weeks after COVID-19 started to rapidly spread in the United States. Naomi is sheltering in place at her parents’ in Washington State after unexpectedly getting stuck there, and having the next two months of gigs canceled. Lee is sheltering in place in Miami, with gigs also canceled, including the Common Field Convening in Houston TX, although they are both looking forward to its online evolution next month!

What has the trajectory of Bas Fisher Invitational been like? How has it evolved in the light of recent grants from the Knight Foundation or NEA, etc.?

Naomi: As we all wonder what the future brings on so many levels, one thing I want to especially convey in talking about Bas Fisher Invitational’s history is that we have experienced many ups and downs. BFI’s organizational model has long responded to moments of surplus and scarcity. As an artist-run space, we’ve been through a few iterations, iterations shaped by the availability of space, access to funding, and the curatorial interests and goals of artists that have worked with us. With one eye towards extreme funding uncertainty (in light of the cascading effects of COVID-19) and another towards the long game, we’re thinking now about how BFI has only been able to endure for 15 years because of our ability to adapt to environmental change.

BFI was born in late 2004 the way many artist-run spaces were: we had extra space and wanted to boost peers we believed in who had not been discovered by the various art worlds.

As Miami was still recovering from the economic shocks of 9/11 and the dot-com bubble, our art community received a remarkable stimulus package in the form of Art Basel Miami Beach (2002). After sharing a studio in a gutted apartment on the bay, and another in the space behind our buddies Maria and Anna Maria’s vintage store M80, Hernan Bas and I were offered a huge studio space by Craig Robbins in the Design District. The space offered so many possibilities. As artists, we could work huge! Hernan and I divided up the space by building some walls and we started organizing shows. Practically, it made a lot of sense to have our studio in the same building as the exhibition space – it enabled us to be there regularly so we could actually have hours and not just be open by appointment.

It was an amazing space, thousands of square feet. In the back, half chipped off of one wall was the remnants of a Jorge Pardo installation. When there was a big thunderstorm the roof would leak, so we had strategic buckets doting the room. In October 2005, I decided to stay there alone to paint while Hurricane Wilma passed over, but quickly realized it was a bad idea when the electricity went out and the skylights in the center of the building all blew out, bursting open BFI’s locked doors with the force of the wind. Skip ahead to present day, and our old DIY space is now a Versace store. Somewhere in between, we staged early shows by Jessica Dickinson, Ryan Trecartin and Lizzie Fitch, Alejandro Cardenas, Jen Stark, and so many others, while we were learning best practices for running a space.

While in this first location, the Knight Foundation started its Challenge program. I applied to the first iteration and was amazed to get it! This coincided with the 2008 recession, and by receiving the grant I had miraculously created a much needed day job. At that point, Hernan had dropped out, and Jim Drain had dropped in, so we split the salary and made less than we would have had we worked at McDonalds. As we slowly grew, we hit the ceiling of fundraising possible with a fiscal sponsor, so we applied for 501c3 status with the help of our longtime former Operations Manager, Danielle Bender. We have been a 501c3 non-profit since 2015.

In 2012, due to development projects in the Design District location, BFI moved to the Downtown Arthouse, a raw space in Downtown Miami provided in-kind by Miami World Center real estate investors, which was home to several other artist-run organizations and within walking distance of the newly constructed PAMM. During this same time, to expand the impact of exhibitions, we also pushed ourselves to bring art outside the walls of our space. It began with a project called WEIRD MIAMI, which started with artist-led bus tours and evolved into a multi-platform initiative of walks, talks, tours, site-specific performances, and educational outreach, and was the foundation for our shift to becoming fully nomadic in 2016 after losing our second physical space.

July 22nd, 2018, BFI at Mangos Tropical Cafe, Miami.

Lee: Nomadic Miami has been BFI’s primary program since 2016, staging site-specific projects by artists across the city in locations (outside of the white-cube) that they decide are more interesting environments to contextualize their work in. Nomadic Miami projects have taken place at botanical gardens, subtropical shopping malls and ice skating rinks, in the ocean at sunset, on a basketball court in the suburbs, in a stuffed-to-the-gills toy store, and other only-in-Miami sites.

The first Nomadic Miami project I worked on when I started working at BFI full time in 2018 was Percolate Anything You Want to Call It, a group exhibition in Mango’s Tropical Cafe. Natalia Arias, Audrey Gair, and Marines Montalvo conceived of the show when reflecting on the most influential aspects of their hometown. Creating work specifically for the historic Mango’s club venue, the work in the show relished in the dance floor’s power while exposing its often consequent gloom.

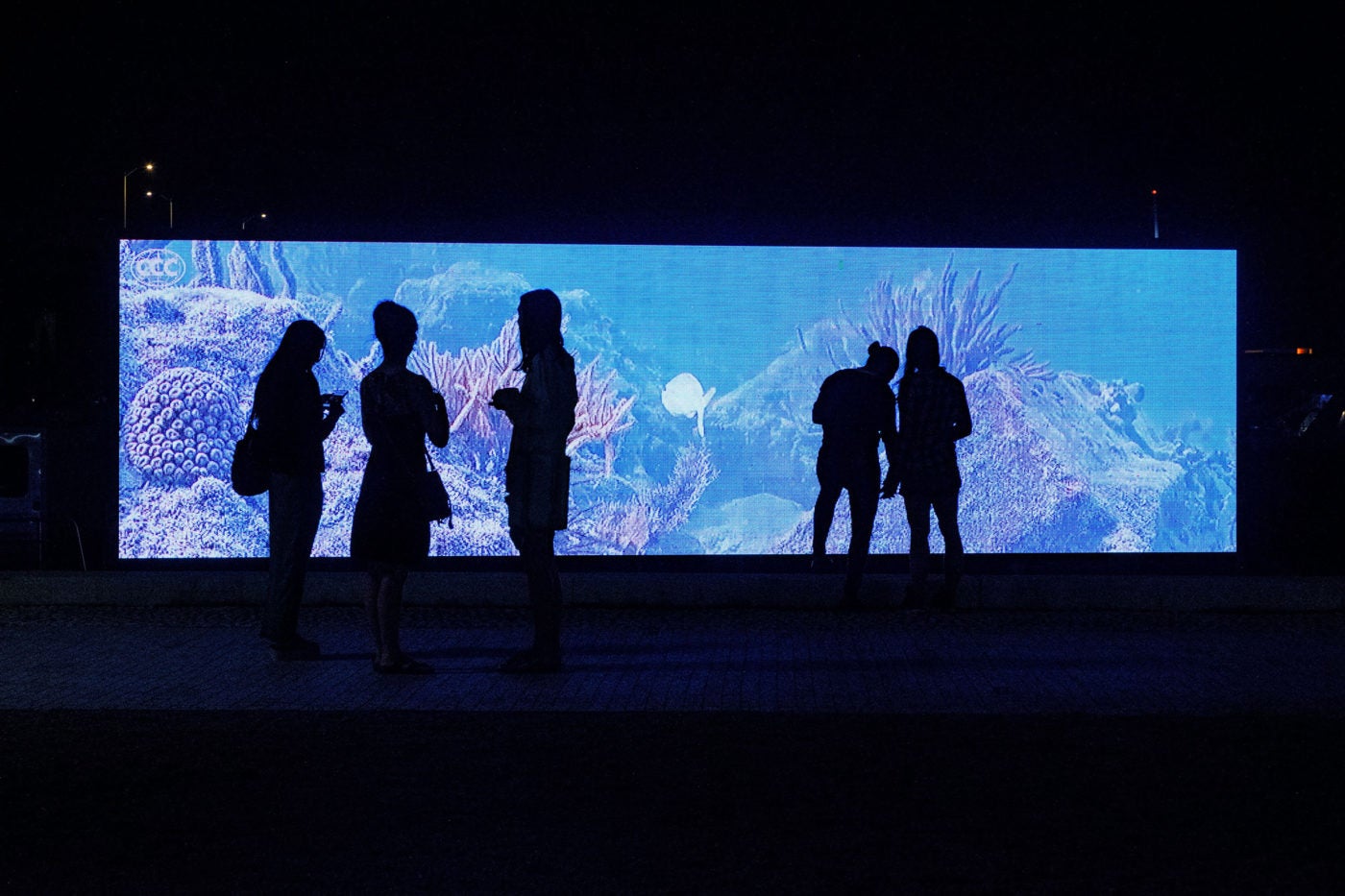

Over the past year, we’ve been working to evolve Nomadic Miami into its next iteration, which we’re calling WATERPROOF. We’re continuing to organize site-specific projects and exhibitions, but we’re doing so with a heightened focus on the environmental issues facing South Florida as a response to the growing importance of similar themes in the practices of many Miami artists. Last month we launched the Coral City Camera, a multimedia artwork and scientific research tool by Coral Morphologic, as a part of WATERPROOF, in collaboration with Bridge Initiative, an organization that supports art for environmental advocacy, telling powerful stories that move people from apathy to action.

Naomi: We just completed our first NEA grant for Coral City Camera (CCC), which was to present the artwork, which revolves around a 360 degree underwater livestream of an urban coral reef, as a large scale video on a boat above the site of the artwork. After applying for three consecutive cycles, being awarded an NEA grant is a huge milestone for us, validating our complicated, shifting, and critical philosophy of producing and presenting art.

A lot of artist-run spaces position themselves against an institution or institutional idea. Is that the type of space that BFI occupies?

Lee: We see BFI’s niche in the local arts ecosystem as a space to primarily serve emerging artists, giving them the time, support and resources to realize ambitious solo projects. Many of these projects have been stepping stones into more institutional spaces. Right before I started working here, BFI produced a show by Jamilah Sabur, titled Beneath the rivers, there are no borders, and while I didn’t see the BFI organized project at the Little Haiti Cultural Center, I did see Sabur’s installation at the Hammer Museum last year that grew from the BFI project, and utilized some of the same visuals she had weaved into the performance in Miami.

I think we try to do a museum quality job in all of our exhibitions, but at the end of the day remain proudly scrappy, returning countless televisions and install supplies to big-box stores, and wearing countless hats as simultaneous curators, writers, artists, accountants, art-handlers, PR strategists, grant writers, and graphic designers.

Naomi: Instead of thinking of opposition I think more about “being the change you want to see in the world.” In 2010, A.L. Steiner and K8 Hardy did a talk at BFI that introduced what would become W.A.G.E. (Working Artists in the Greater Economy). Once a certification process was in place, BFI was the first organization in Florida to become W.A.G.E. certified. This was easy for us because we had already grown our funding base enough where we could budget artist fees and production support. And more importantly, we believed that artist fees and production funds are crucial for arts institutions to provide. Having had many institutional and museum shows myself, I’m always shocked at the meager funds budgeted for the art to be made and the artist to be paid. I’m so proud of the impact our W.A.G.E. certification had on larger institutions in Miami. The director of another institution called me to talk about it. She really wanted it to happen, it took having the language and certification process of W.A.G.E. to convince funders that more should be allotted to artists. The fact that a tiny org like BFI could do it made it embarrassing that bigger, more established institutions are not at that standard.

As artists yourselves, can you reflect on how operating an alternative artist-run space has affected or influenced your own studio practices?

Lee: I feel really fortunate to have a day job that teaches me so much, and has me in constant communication with other artists, many of which I did not know before starting to work at BFI. Since it’s mainly Naomi and I engaging with the artists we’re working with, it leads to really personal connections, and lots of conversations about each other’s practices, trajectories, and goals. After talking with Deon Rubi, an amazing artist and designer we produced a show with in 2018, I started designing a sculpture that would be CNC milled, a process I had no experience with but she suggested as the best way to get the form I had in mind.

More recently, we’ve been working on this ongoing project with Coral Morphologic, and I’ve had the pleasure of spending time in their studio which is full of tanks that hold a diversity of marine organisms (fluorescent corals in particular) second only to the ocean. In working with them, my admiration for bioart has been rekindled. Although I’m not planning anything at the moment, I can anticipate a shift in my work towards multispecies collaboration, working with living things instead of engaging with them representationally.

This is already something I aim to do with the Institute of Queer Ecology, a project I began in 2017 that has grown into a network that produces exhibitions, publications and performances that works to imagine and realize an equitable future for all species. Working at BFI has taught me a lot, but most importantly is the nitty-gritty logistics of running an artist-run space. Grant writing, accounting, and other skills can quickly evolve a DIY ethos into a fledgling organization, and with what I learned so far at BFI, I was also able to secure a Knight Arts Challenge Grant for the Institute of Queer Ecology, which will provide significant support to a project that for 3 years has been largely a labor of love.

Naomi: Since I have been doing this for 15 years, it’s hard to separate my art practice from aspects of running a space. Studio visits with peers have different layers. Attending art fairs and things like the Common Field Convenings are opposite sides of the art world, both of which can learn from each other. I get to experience art scenes all over the place through my own projects and incorporate that knowledge back into BFI. Recently, I was fortunate to attend Bande À Part, the 2019 UKS conference on independent art institutions in Oslo because it was on the way back from a residency, which gave me a better understanding of European DIY projects. Self-taught non-profit administration skills help me manage my large scale public art commissions. I have deep appreciation for the amazing cultural affairs departments in Miami, I’ve learned the most about grant writing and administration through their feedback.

My experience running BFI has reinforced valuing slow progress against quick ascents. I’ve witnessed so many wonderful artists have their safety nets withdrawn when their sales don’t quadruple quick enough. It is important within small arts communities to see beyond the smoke and mirrors of success. I love BFI and what it has done and is capable of doing, but I’m also very open that it’s my form of a safety net, providing income stability so my practice can weather market fluctuations.

Doing this work also highlights the importance of mental health care. I don’t think I would have made it this long without going to a therapist. I’ve learned sometimes the most talented artists are their own worst enemy, either through psychological self-sabotage, or not being able to survive in an art world that requires artists to be administrators. I see this issue as a result of the lack of social safety nets. The larger culture does not value a supported dedicated art practice, rather the myth of self-sacrifice for their vision.

Jorge Elbrecht and Max Hooper Schneider, Coral Cross III, December 3rd, 2016,

BFI at the Colony Theater, Miami Beach.

Has being a nomadic space been helpful or harmful?

Lee: I see BFI’s turn to nomadic programming as a way to be less complicit in gentrification, while also foregoing the gallery in exchange for shows and programs embedded in the larger matrix of the city. BFI has found ways to engage the artistic community in new, exciting ways while allowing our audiences to stumble upon surprising experiences, whether that meant a recent performance series by Jenna Balfe that sprawled across downtown, connected by the city’s Metromover train, or a 2016 show by Max Hooper Schneider and Jorge Elbrecht at the Colony Theater in Miami beach that inverted the audience by having them on stage with an installation involving a hot tub full of crabs as a performance happened below.

Naomi: It has been freeing to be able to find ideal sites for each project, and experiment with ways we can bring art to different neighbors instead of being the first evidence of a coming wave of gentrification.

However, the logistics of government permits or private permissions requires additional behind the scenes labor, which is the kind of labor few funders want to pay for. Unlike our first physical space, where we knew where to put the buckets when it rained, there are always unforeseen issues with each temporary venue that pop up. Press has been challenging, as few outlets want to cover projects with a short duration.

But this had led to new solutions, lots of partnerships, and more collaborative ways of working with other arts organizations near and far. Ultimately, scarcity of desirable real estate and funding is a problem that looks like it’s going to get worse before it gets better, so I hope that this model will further cultivate artists’ hybrid existences as creators, presenters, and workers.

Are there plans to one day have a permanent space again or are the goals of BFI more rooted in site-specificity and temporary exhibitions that align with your program, Nomadic Miami?

Lee: There are no plans on the horizon for BFI to lay down roots anytime soon. We’re excited about our upcoming WATERPROOF programming in collaboration with Bridge Initiative, which continues our site-specific interrogation of South Florida. Personally, I see a permanent space as a factor that can really bring stability to an organization, but (regardless of the issue of having the capital to secure a permanent space), I’m hesitant to believe that fixed-locations (at least coastal ones) will continue to equate stability as the climate crisis intensifies. In 2020, a 30-year mortgage in Miami is now directly on a crash course with estimates that by 2050, Miami may be 30% underwater. I think for the time being, we’re hedging our bets that our flexible program might just be the most resilient.

Naomi: After doing the precarity dance for so long, I want nothing more than stability. Right now, in the beginning of COVID-19, sheltering in place, watching corporations getting the lion’s share of the economic stimulus, I deeply worry about all small businesses. I’m grateful to have participated in and witnessed the production of many incredible projects outside of (and questioning) the white cube. I keep thinking about the symposium we produced for AST (Alliance of the Southern Triangle). When a climate modeler was asked what role he thought artists could play in combating Climate Change, he replied something along the lines of, “Unfortunately the only time society seems willing to make major changes is after a disaster has struck. Artists should work on visualizing and constructing a better future, so when the next disaster strikes, plans are ready.”