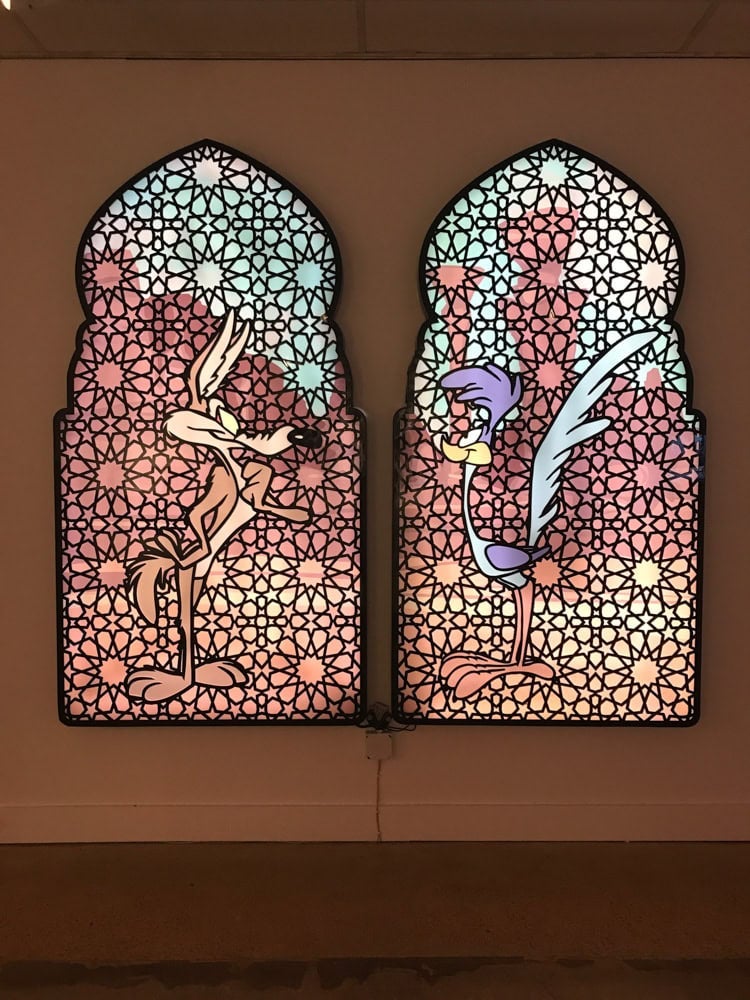

2016, by Maha Malluh.

Considering our nation’s tenebrous sociopolitical climate and increased xenophobia regarding the Middle East since September 11, 2001, it is still a slight surprise to see an exhibition in the United States, and especially the South, made up completely of works from Islamic countries. During a memorable 2009 speech at Cairo University, President Barack Obama said that “America and Islam are not exclusive, and need not be in competition. Instead, they overlap, and share common principles—principles of justice and progress; tolerance and the dignity of all human beings.” The recognition of such shared values between the Arab world and the West is a major theme of “Desert to Delta: Saudi Contemporary Art in Memphis,” but even more so is the recognition of our shared strife, when pain arguably inspires a stronger bond than joy.

“Desert to Delta” was organized by the King Abdulaziz Center for World Culture (Ithra) in Dhahran, Saudi Arabia, and curated for the Art Museum of the University of Memphis (AMUM) by Leslie Leubbers and Edmund Warren Perry, Jr. Citing global issues, such as social inequality, economic disparity, and loss of traditions, the curatorial statement on the wall at the exhibition entrance draws connections between the cultures of Saudi Arabia and Memphis and the shared challenges that are burdensome to the contemporary artists who grapple with them.

The exhibition, including 21 works by Saudi visual artists and a video collective, begins with a focus on Saudi women by women artists. An installation by Shadia Alem, Negative No More (2004), comprises thousands of photographic negatives, connected at the long edges to form a quiltlike blanket. The blanket of negatives cascades from a wall above eye-level, and provides the surface for a video projection of a Saudi woman dressed in a traditional black abaya cloak, covering her body from head to toe. Just around the corner is Food for Thought Almuallaqat 4 (2016) by Maha Malluh. Hundreds of used aluminum cooking pots of varying sizes hang on the wall, arranged in a large square. The pots, undoubtedly used primarily by women, were collected by the artist from flea markets around Saudi Arabia and are meant to represent the shift of importance from oral to visual culture over time. The pots are visual stand-ins for the oral exchanges of stories that occurred during the use of the pots.

In the same room, Tree of Guardians (2014) by Manal Al Dowayan steals the show with exactly 2,000 leaves cut from thin, shiny brass hanging end-to-end with nylon thread as if raining from the ceiling. The leaves are carved through with a delicate lacy pattern and are inscribed in ink with the names of often unrecorded and unremembered maternal ancestors, taken from the family trees of 400 participants whom Al Dowayan asked to chart in order to determine at what generation the women disappear from history (according to Al Dowayan, it is the ninth generation, much sooner than men).

In each of these three works, the value and empowerment of women are placed at the center, finally touting the critical contributions women play in preserving a heritage that does not reciprocate. There is also an ironic, consistent use of traditional objects as media to convey a message of a national clinging to harmful traditions that begins in this first room and continues throughout the exhibition.

Although religion and politics are ever-present undercurrents, they take more physical shape in such works as Eyad Maghazil’s Breaking News (2011), which displays 3,000 red-painted toy soldiers packed into a clear case. An iconic figure from American boyhood, the toy soldier hits home for viewers who see the carnage of war under a microscope, not unlike watching the television news, the red paint symbolizing blood and the clear case a grave. Oil painting takes on new meaning with Nugamshi’s Mirage (Saraab), 2016, a video sequence in which the artist, dressed in a white thobe, seemingly paints the air in crude oil against the landscape of the Riyadh Desert. The desert setting and the fading in and out of the artist is mirage-like, a metaphor for the elusive merits of the oil industry in Saudi Arabia.

Globalism, Americanization, and the intrinsic dilution of a single culture are addressed in Huda Beydoun’s photographs Tagged and Undocumented 4 and 5 (2013), which use the shape of Mickey Mouse’s head to cover the faces of undocumented and unrecognized foreign workers, camouflaging the mistreatment of the immigrant class with “happy American thoughts.” Ghada Da’s Sculptural Color from Historiographical Perspectives of Scent (2017) is an exploration of the relationship between scent and culture and is one piece that incorporates Memphis directly. Standing just in front of the roughly 8-by-8-foot canvas, you can smell the contents of the top coat—bergamot, cedarwood, nutmeg, and sandalwood, and bacon grease, barbecue sauce, and Elvis Presley cologne, to name a few.

The crown jewels of a multicity tour of the United States, the works in the show traveled to California, Colorado, Maine, Michigan, Texas, and Utah before arriving in Tennessee, which explains why a demonstrated tie of the works and their creation directly to the city of Memphis is rather weak in comparison to the aims laid out in the exhibition’s curatorial statement. Neither the works nor text panels throughout the gallery make significant reference to Memphis beyond the introduction and Da’s Sculptural Color, so what is positioned in the curatorial statement as an “embracing of cultures” is actually one-sided and highly generalized.

Nonetheless, “Desert to Delta” still makes a case for cross-cultural unity and an appreciation of Saudi art and artists. With minimal guidance, viewers empathize by identifying aspects of Saudi life in the artworks that overlap with the American lifestyle they know. Many comprehensive and wide-reaching exhibitions feature just one showstopper or two—a work that is large and intricately detailed with many parts that stands out from the otherwise traditional wall canvas. “Desert to Delta,” however, is chock-full of elaborate and interest-piquing compositions of unusual media. It reminds me of Crystal Bridges’s “State of the Art: Discovering American Art Now” in its expansive coverage of subject matter, medium, and process of an entire country’s contemporary art scene.

Beep Beep (2015) by Rashed Al Shashai is an appropriate work to sum up the whole exhibition. Mortal enemies Wile E. Coyote and Roadrunner stare at each other from the foregrounds of two separate mashrabiya-shaped light boxes, the Saudi architectural skyline and red sand color palette in the background. Here, Al Shashai comments on the need for cultural tolerance among peers—standing side-by-side with people who are different from us and allowing them to coexist peacefully—a need that transcends Saudi Arabia, and even the United States.

“Desert to Delta: Saudi Contemporary Art in Memphis” is on view through January 6.

Elaine Slayton Akin is an arts writer and nonprofit professional in Nashville by way of Little Rock. She is a member of the Inter-Museum Council of Nashville. Her writing has been featured in Nashville Arts, Arkansas Life, Number, and At Home in Arkansas magazines.