The racial category and social position constructed as whiteness operates through a set of unmarked and unnamed cultural practices that are designed and enforced to privilege its members. The art museum, with its rooms full of objects negotiating and guiding our tastes, values, and assumptions in space and time, is one of the most visible structures of whiteness. It is a place where the “unconsciousness” of Western (art) history and its roots in capitalism, racism, imperial colonialism, and heteropatriarchy can perpetuate and manifest unchecked, based on institutional presumptions of a white audience and white critical network amplifying and naturalizing a whitewashed cultural history. Recent calls to decolonize the museum and hold such institutions and their leaders accountable for their lack of concern for marginalized artists and audiences have posed radical, urgent forms of critical intervention necessary to repudiate the exclusionary practices and privileged narratives reproduced in contemporary art institutions, namely, what it might mean to present artists and histories of art that face these uncomfortable facts head on, and perhaps upend the embedded conventions of structural racism.

The assumptions and supremacy of whiteness are frustrated at the Spelman College Museum of Fine Art because of the centrality of black women in its collection and in art historical narratives presented there. The museum’s ambition to display work by black women artists pressing the boundaries and conventions of contemporary art swells expansively in the museum’s spring exhibition “The Evolution of Mimi,” a midcareer presentation by Deborah Roberts, an Austin-based artist gathering national attention for her sharp examinations of black girlhood and the legacies of colorism and racism for young black women. Aware of the unrealistic standards and pressures facing black women in a society shaped by white standards of beauty, Roberts reconstitutes the misogynistic and racist stereotypes inflicted on black women into powerful images of female strength, vulnerability, and self-love.

The exhibition contains over 50 works in a range of mediums, charting the important transition Roberts made from early figurative painting to her more recent work in collage and hand-drawn seriagraphs. Known in her early career as the “Black Norman Rockwell,” Roberts’s work draws deeply upon work by preceding generations of African-American artists and the traditions of narrative and illusionism that run deep in African-American art, and builds upon the work of African-American feminist artists who have reclaimed and subverted racist and sexist stereotypes of the black female body. The large canvas Ain’t Yo Mama No More (2006) takes up the pervasive and enduring racial caricature of African-American women as “happy slaves.” The Mammy’s wide grin, loud laughter, maternal loyalty to her white family, and extreme work ethic posed as evidence during Reconstruction and the Jim Crow Era of the humanity inherent in the institution of slavery, however, as Roberts’s painting makes clear, a new dawn and new image of a black women has emerged out from under Mammy’s skirts. Amid a swarm of black crows–perhaps a stand-in for the patriarchal body politic that guides American history and black disenfranchisement–Roberts’s monumental maternal figure un-does the representational politics and racist context of black female representation in order to create space for a more nuanced and empowering image to emerge.

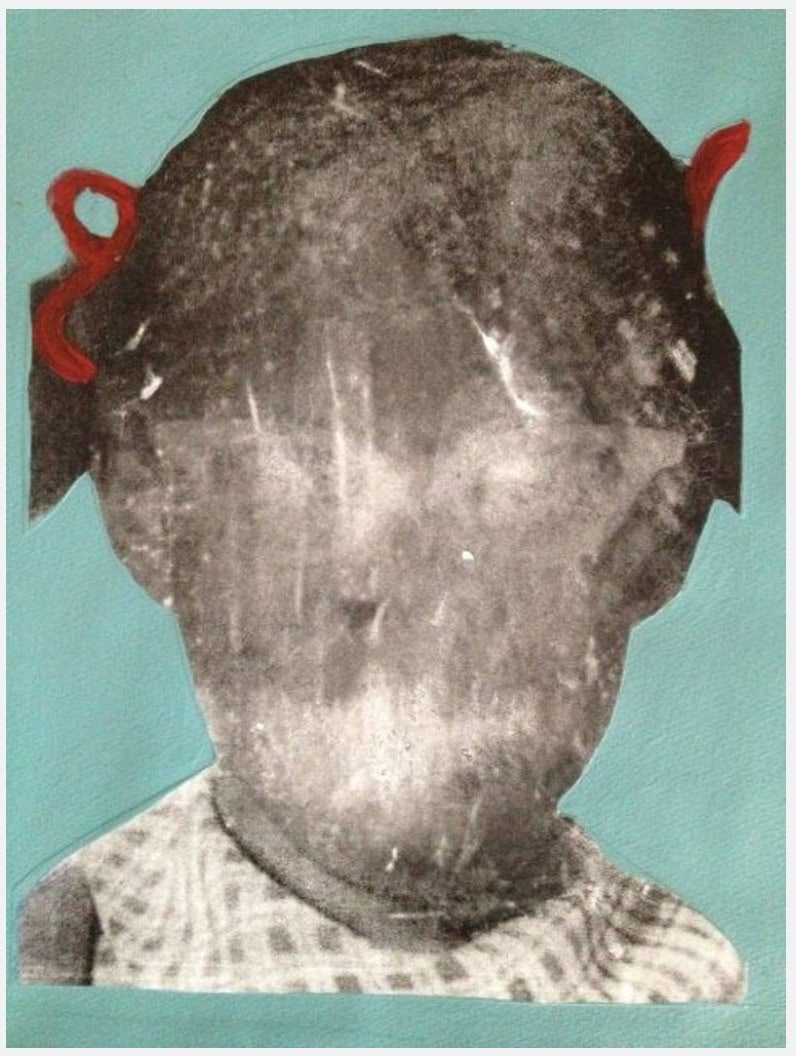

By engaging the visual fragmentation of collage as a metaphor for black women’s reconstitutions of selfhood, Roberts has opened up new lines of formal and conceptual inquiry for the representation of the black female body and its inherent politics. Adopting collage as a radical verb, Roberts teases out a multiplicity of faces, features, and accessorizing objects from our vast commercial image culture and moves them into new figurative arrangements that embrace the collisions and juxtapositions of their making. The result is a powerful cohort of black girls whose bodies have been brought into being by the sharp compositional decisions of the artist, but whose relationship to the fragmented imagery and piecemeal ephemera is decidedly ambiguous.

This iconographic ambiguity is reified in the title of the exhibition, named after a significant series of collages begun in 2011 titled The Miseducation of Mimi. A blend of the titles of the 1998 Lauryn Hill album The Miseducation of Lauryn Hill and the 2005 Mariah Carey album The Emancipation of Mimi, Roberts uses this amalgamation to invoke these two music icons and point to the ways in which their contributions to music history and relationship to media controversy impact society’s notions of female artistic power and its relationship to selfhood and self-image. Hill’s sensitivity to the politics of language and her fervent embrace of her own blackness contrasts with Carey’s glittery pop image and anxious relationship to her biracial ancestry. Even so, these musical artists share a volatile relationship with the public that speaks to the unjust expectations put upon women of color by the manipulative and sexist recording industry. Much like Roberts’s collaged girls, whose faces and forms are cut, ripped, sliced, and reshaped into new configurations, so too is the legacy of black women artists and black women whose bodies are interpreted, manipulated, and rendered invisible by a society who does not value them.

Yet these collages are not just icons of violence but invitations to engage more thoughtfully and sensitively. Long and close looking is what collage demands, and Roberts’s collages are no exception, revealing the spirit of the artist’s mission: “When you look at my work I want you to look at every part of the girls’ faces…these faces are demanding, they’re asking you to see their humanity and individuality. I want to force you to see black people, black girls as not as this monolithic being but as individuals.”

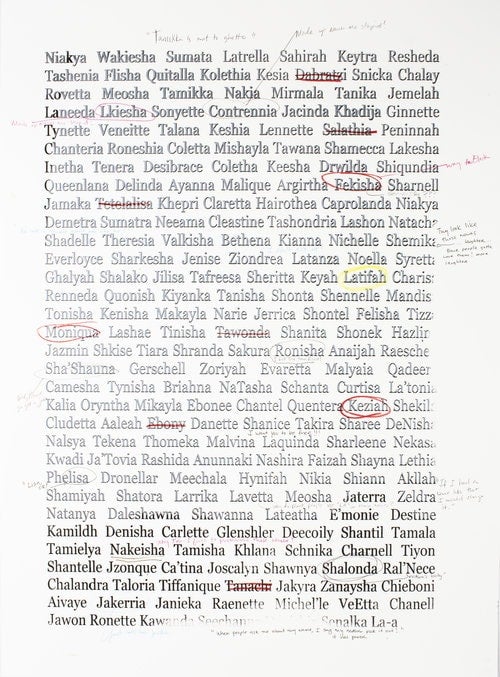

While the collages form a major portion of the Spelman exhibition, I was drawn most to the series of hand-drawn text-based serigraph works, the Sovereignty Series, which present lists of stereotypical black women’s names, such as Sharkesha, Shonique, and Queenlana. Many of these names are underscored with a red wavy line—a suggestion from word-processing programs that these names are misspelled, marked as incorrect and unintelligible within white discourse. A 2016 study supported by the Harvard Business Review indicated the high prevalence among minority applicants to “whiten” their resumes and downplay any cues or references to their race in hopes of boosting their success in landing a job, as the bias against minorities runs rampant throughout the screening process. This often involves changing one’s given name to something more conforming and assimilative to WASP culture—an act that resonates when one remembers that often the first act of freedom for slaves after emancipation was to name themselves and their children. In these works, Roberts pushes collage’s foundational engagement with the “signs” of the world into the realm of language and underscores racism’s nefarious presence within all of our structures of communication and visuality. It is also, however, a call to celebrate blackness in all its forms–an exciting and potent proposition in an art institution that serves an audience of young black women.

Deborah Roberts: The Evolution of Mimi is on view at the Spelman Museum of Fine Art through May 19, 2018.