Southern culture, though it has a complex relationship to its history and populations, has a lasting and undeniable relationship to the land. From politics and social movements to personal accounts and lamentable opinions, people are often concerned with one of two things in regards to the South: what it used to be and what it might become. With the talent of precision, Carly Drew folds both of these narratives into her depictions of the current landscape—beautiful whether inhabited or preserved—with all its layered and loaded history. Drew’s work in “Hatched” at Kai Lin Art examines these narratives, the forces of nature on the landscape, and the impact of the land on the people who live off it.

When people describe the South, they begin by defining its geographic boundaries, even though those boundaries are contested or vague. The South has its own culture, one embellished with myths, fortified by tradition, and bound to a sense of place. For as long as it has been a self-designated region, change—political, topographical, industrial, migrational, social—has been as much a part of Southern culture as has its food, folklore, and lifestyle, even if the change is unbidden.

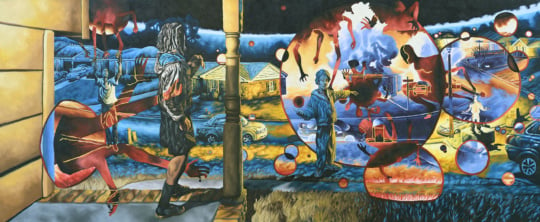

Pulling from the images and the history of the region in which she grew up, Drew paints to harness the strong narrative component of this historical change through an art form emblematic of nostalgia and regional pride: landscape painting. But the work is about more than nostalgia and reverence for the land of a region. Her work in “Hatched” isn’t idyllic or glossy or grandiose. It depicts the agrarian livelihoods of its residents; some works even look more like the rural site of a natural disaster.

Drew was raised in both the southern Blue Ridge Mountains of South Carolina and the Appalachian region where her grandparents resided. She says she began focusing on work about the landscape after a family spat over land ownership and mineral rights following her grandfather’s death eight years ago. Drew is intrigued by how landscapes are depicted and understood dichotomously: the population that lives off of the land has a different perspective than those who don’t. Her art exhibits both perspectives, and she implements a layering process to metaphorically represent them. A beautifully rendered drawing of a family’s rusted pickup truck is juxtaposed against a landscape with lines from a topographic map, the result of collected data. Personal histories, close-up exploration, reliance on its resources—these viewpoints all provided vastly different portrayals than maps, statistics, and topographic data could yield. Drew builds up layers of typographic drawings, documenting the history of land usage and evolution; a lot of her work portrays the industries of mining, farming, lumber, natural gas, and hunting. To her, the landscapes become “a small compression of the history, ideas, and our personal connection to the land.”

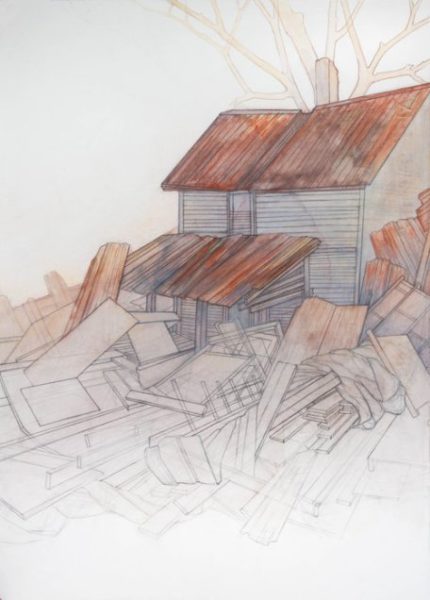

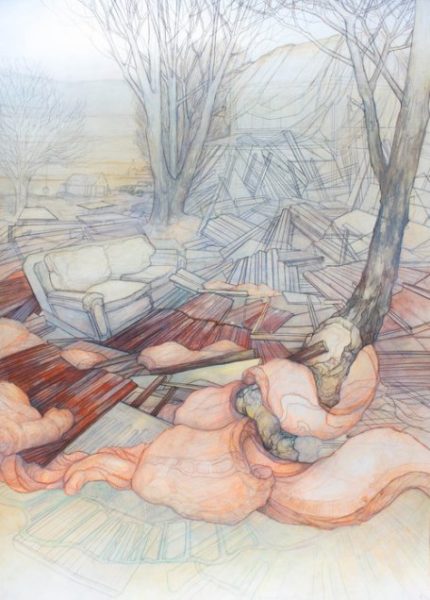

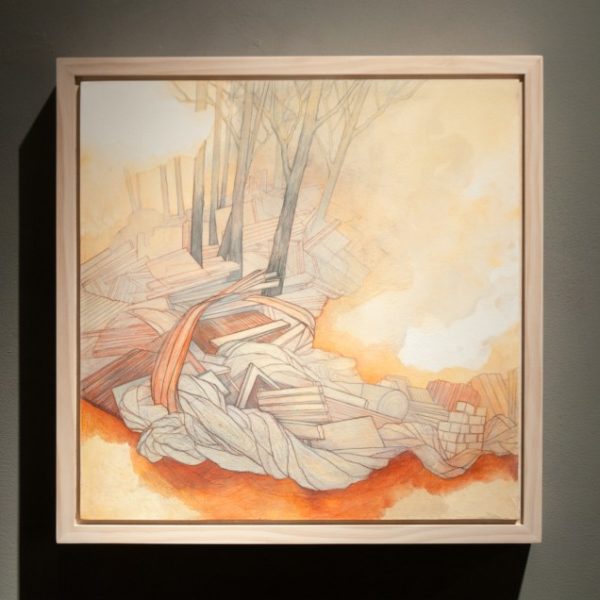

In the work Will and Testament and the Reckoning series, change was the result of nature’s wrath. Farm houses look as if they were in the path of a tornado, or of a forest fire that swept across an already incinerated landscape after months of extreme drought. Piles of broken wooden planks fill the frame. Upturned furniture sits atop homes, dismantled by the wrath of unforgiving natural forces. Even in light of the destruction, the landscape is beautiful, and the artist’s touch graceful. She paints with washes of colors that look as if they were collected from pockets of pooled water in red clay soil after a hard rain. Steel blues are subtle, blotched, and running.

Drew’s drawing process is visible beneath thinly applied layers of graphite, Prismacolor, and watercolor; her marks reveal her decision-making and the buildup of narrative, one over the other. Just as changes in the landscape are visible and reshaped by history, so too has her hand mimicked that development on the page. Drew emphasizes the importance of visual transparency throughout her series as a way to denote transition, time, and the transiency natural to the life of the land.

Sleeping Giants hints at the earnest living residents of its landscape make with silos, a farm, a truck. In other pieces, the layered drawings of barns and sheds resemble blueprints, but washes of faded color and sketched trees naturalize their place in the landscape. In Contested Grounds, a simple home, probably built by its owner, sits nestled in a thicket of evergreens, not far from the source of its construction materials. Drew’s line work wraps and drapes around forms like the tracing of a topographic map. Delicate lines, like rings on a tree that belie its age, wrap around features in the landscape. They roll with the hills and crease at the divots in the ground.

Cut-down trees, homes, silos—the objects in the landscape are ghost-like. They seem to be fading, marking the age and history of the land like carbon-life. The people in these narratives are absent but a truck, a silo, a tattered barn stand in for their livelihoods, their land ownership, the life in the only country they’ve known.

But the work is not just nostalgic, not just archival, and not just delicately rendered. As Drew stated in an interview, it tells “a larger story about the contemporary rural landscape, its people, and what living in these places where old and new coexist is like,” a striking contrast ever-present in the South. She feels a sense of place for a region where artists are often overlooked and its residents are misrepresented and misunderstood.

Carly Drew’s work in “Hatched” at Kai Lin Art will be on view through March 10.

Jac Kuntz is an arts writer, editor, journalist, and artist living in Atlanta. She is a recent graduate of the Masters of Arts Journalism program at the School of the Art Institute of Chicago. She also holds a BA in Psychology and a BFA in Painting with a concentration in art history from Clemson University.