Is it possible to forget that war exists? If you read the daily headlines, it is difficult for the death tolls and protests not to seep into your subconscious as you go about your day. But for those of us who are not in the middle of a war zone, the struggles in other parts of the world can all too quickly get pushed to the perimeters of our reality. Artist Caomin Xie’s “Black Lotus“ exhibition recently on view at Fay Gold Gallery, included a strong collection of kaleidoscopic mandalas of thickly applied oil paint on canvas that caused me to pause and reflect on the steady chaos that surrounds us.

The artist said, “every time you shake a kaleidoscope, you don’t know what outcome you will arrive at. Chaos is a normal condition, and the persistent condition is that of accident.” Xie has been working with mandalas since about 2008 and wishes to transform “the rotten into miracle.” The artist runs found images of broken walls and wreckage through specialized software that creates the kaleidoscopic shapes. He then takes the digital creations and transfers them to the canvas in a random manner.

Xie’s mandalas of blacks, grays, and piercing whites incorporate references to demolished buildings, war, terrorism, and its victims. This limited color palette allowed me to focus on the content and patterning of each mandala—it invited me to look closer without distraction. Xie, who is known as Alan in America, walked me through the exhibition and explained what these artistic meditations mean to him as an artist. This body of work, which could seem stark, is hopeful for him in its depiction of the circle of life and in the mandalas serving as a prayer for humanity.

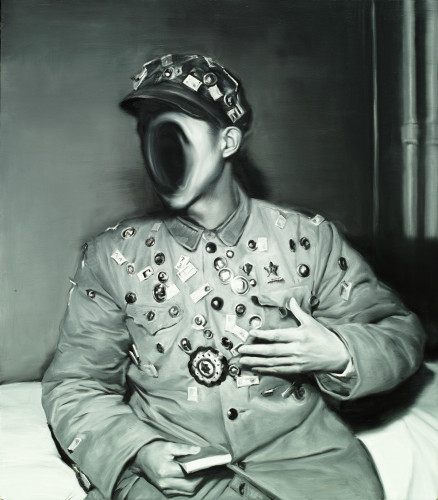

Among these contemplative circular formations are other works that depict people, in group settings or alone, with their faces dissolved into swirls of paint that seem to liquefy or marbleize on the canvas. These pools of abstraction create a sort of void where facial features should be. Xie has been told that the figures bring to mind such things as the performers in the Beijing opera who wear masks of different colors to reflect different characters, Edvard Munch’s The Scream, and the changing face of China. In this collection of faceless humans, their individuality stripped away, I couldn’t help but wonder who they were and what their personal narratives were.

In Doppleganger, we see two identical soldiers in a painting that looks like a soft focus photograph. This lack of crispness lends a dreamlike quality to the men, making them appear like toys. There are two ghostly and psychologically charged group portraits on view that are mirror images. The white circles depicted on the people’s clothing are the badges of Chairman Mao. French psychoanalyst and psychiatrist Jacques Lacan believed that “the formation of subjectivity is the mirror image and through the mirror image we start to recognize the I.” Believer shows a highly decorated soldier, again faceless, whose medals and badges seem to consume him. He sports a hat adorned with even more symbols of honor. The reference for this piece was a war hero from a propaganda photo. The soldier is seen turned to the side, gesturing as if in conversation, perhaps giving a speech about his experience on the battlefield. In one hand he holds on tightly to a copy of Mao’s “Little Red Book,” as it became known in the West.

In Mandala #42, which refers to the Malaysia Airlines Flight 17 that was shot down in July, there are white dashes huddled together in the center of the composition. What they symbolize is left for the viewer to decide; Xie allows you to project your own thoughts, worries, and dreams onto them. The mandala format is present in many different religions, but Xie told me that he adopts them from Buddhism. The circle of each mandala represents a cycle of beginning-development-corruption-beginning. The lotus flower, which shoots up its blossom from the bottom of murky ponds, is a very important symbol in Buddhism. It tells a story of transcendence and transformation.

The most visually striking piece in the show is Mandala 33, which depicts the aftermath of 9/11. We see signs for Wall Street, the dying architecture, and the faces of people lost in the rubble. A row in the circular shape looks like repeated dragon heads. Xie didn’t realize this until he finished the piece but is very pleased with it. He feels that it addresses the currency war between China and the U.S. and the alarmist cries from Western media that China is taking over. I can see the Chinese dragon overpowering Wall Street in this dynamic painting. I asked Xie why he decided to reference an American tragedy, and in response he said, “All terrorist attacks are very important historical events. We no longer talk about capitalist versus working class or class differences. So we forget about war. We pretend that the crisis has been solved.” These works are haunting; they confront ideas of memory, identity, technology, war, change, and our role in the circle of life without giving up on the positivity and progress attained through self-examination.

“Black Lotus” was on view at Fay Gold Gallery, August 7-30.

Sherri Caudell is an Atlanta-based writer and poet.