It is difficult to digest the numerous facets of “Breaking the Mold: Investigating Gender at the Speed Art Museum.” Though the overall installation is visually pleasing, it is quickly evident that the shared aim of the works is challenging representations of beauty, idealization, race, and gender.

Walking through “Breaking the Mold,” visitors encounter representations of the body from various periods of art history, including a 3rd-century Greek bust of Aphrodite and a 19th-century marble statue by Pierre-Jean David D’Angers titled The Young Hercules. Aphrodite’s bust—once a complete form but now legless, armless, and headless—represents the beginning of a longstanding artistic tradition of idealizing the human form, which continues today in mainstream media’s unrealistic depictions of perfect bodies living perfect lifestyles. Other representations of the body, both male and female, can be found throughout the gallery—in the work of James Valerio whose painting Spring Mambo (1986) features the upper half of a reclining nude, her head hanging over the edge of a table, and in Philip Pearlstein’s painting Couple Lying on a Spanish Rug (1971), which presents the cropped bodies of a man and woman in the artificial light of Pearlstein’s studio.

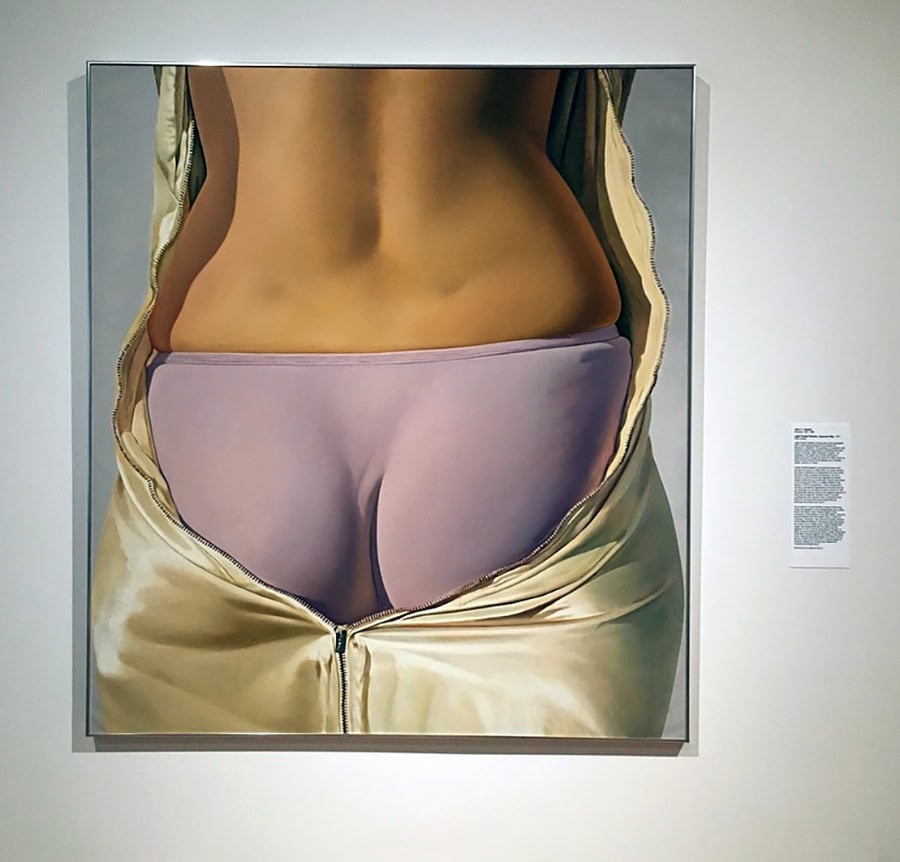

The image in John C. Kacere’s painting Light Purple Panties, Zippered Slip (1971), one of the most “recognized and controversial artworks” of the Speed’s collection, consists only of a female figure’s lower back and buttocks, the latter covered by thin, pale, purple panties, with a tight cream-colored slip partially zipped around her body. Like the bust of Aphrodite, the work is limbless and headless. In a letter to the Speed Art Museum, printed on a nearby placard, Kacere admitted his awareness of the backlash against the painting’s overt sexualization of the female body, but says he felt the feminist movement of the 1970s made it difficult for women to “see the painting without some of the negative aspects of what they have seen as ‘woman’s role’ in society.” Kacere goes on to mention that despite the negative attributes, he finds more women than not seem to like his work, which perhaps in Kacere’s mind pardons him from the fact that he has created little more than a sexualized torso. The clear sexualization of Kacere’s painting strongly contrasts with the canvases by Valerio and Pearlstein, who seem as interested in the settings as their nude figures whereas Kacere is solely focused on the figure.

In the works of Kehinde Wiley, Ebony G. Patterson, and Robert Colescott, the audience is confronted with issues of race and power dynamics. Robert Colescott’s Lightening Lipstick (1994), for example, addresses issues of racial representation and the privileging of light skin tones over dark. The work examines the problems of racial discrimination in the United States and the way people of color attempt to alter their appearance to better meet mainstream idealizations.

Ebony G. Patterson’s work Golden Rest—Dead Treez (2015) is a sparkling, mixed-media tapestry covered in sequins, beads, and crocheted leaves. A cacophony of color and dazzle, the work is overwhelming both in size and glamour. Buried within the layers, fragments of a figure emerge: a pair of shoes, wristwatch, and a discarded jacket. A reference to Jamaican dancehall culture, the work is both celebratory and mournful and is meant to represent, according to wall label, a place where “traditional gender norms could be challenged,” while also shedding light on the “underreported brutality experienced by people of color.” Noting the artist’s intention, it becomes easier to interpret the hidden messages buried under the thick sparkling layers of leaves and fabric. The discarded and bedazzled jacket, for example, represents a young individual exploring their identity, but why has it been left in a crumpled lifeless heap? Joined by the shoes and wristwatch, it becomes clear that those items represent victims whose stories have been left untold.

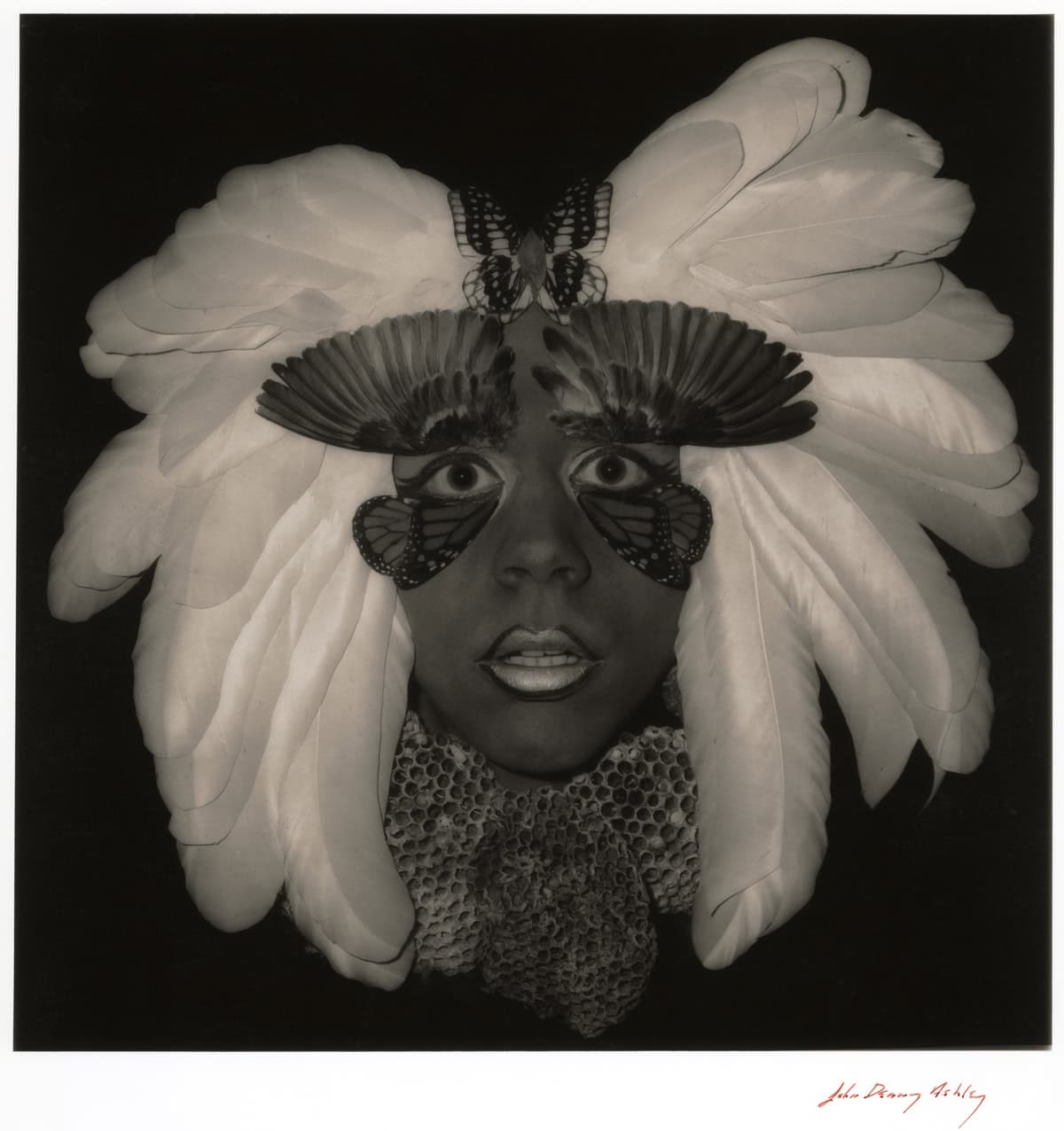

“Breaking the Mold” additionally examines issues of representation within the LGBTQ+ community. Through a partnership with the University of Louisville’s photographic archives, as well as the Faulkner Morgan Archives of LGBTQ history in Kentucky, a series of photographs are presented by artist John Ashley that documents aspects of the LGBTQ community of Lexington in the 1970s. Ashley worked with artist Robert Morgan, photographing him dressed in various handmade costumes and drag. The images combination of costume and dramatic lighting make them akin to movie stills, even as they represent a counter culture not usually associated with Kentucky.

Towards the entrance of the exhibition is Gladys Nilsson’s Studio Seen (1991), a colorful painting featuring a self-portrait of the artist, as well as a conglomerate of variously sized figures moving actively across the canvas. Described by the museum as whimsical, in many ways the action in the painting is much more sinister. Nilsson depicts herself using her television remote control to conjure up various characters in her studio. The characters fill the canvas, scurrying with malicious grins around Gladys as she contorts her neck to take them all in. Placed on a wall next to two pieces from 1994 by Barbara Kruger, Untitled: (Think Like us) and Untitled: (Talk like us), it is easy to see this short series as a cautionary tale, warning us of the power of the media.

In many ways, these works summarize the underlying themes “Breaking the Mold” attempts to illuminate: how our bodies, skin tones and gender identities are presented in everyday media, who is depicted, who is seen as “normal,” and who is seen as foreign or other. “Breaking the Mold” does not shy away from controversy or difficult questions. It reminds us of the significance of representation — who most often gets heard — and offers a voice to the frequently silenced.

“Breaking the Mold: Investigating Gender at the Speed Art Museum” is on view through September 9, 2018.