Poverty is not often romanticized on the big screen. We have Chaplin’s Modern Times, we have Rocky, we have Slumdog Millionaire. But generally, we seem to prefer fantasies about upward mobility and the lifestyles of the superrich as opposed to adventuring in the freedoms of the underclasses. Or, perhaps there are certain agendas behind Hollywood that prefer to direct our dreams toward wealth.

As serious politics argue over the inequality of American incomes, it’s a dangerous time to make heroes out of the poor, but Beasts of the Southern Wild, a break-through indie movie directed by Benh Zeitlin, does just that. Released in 2012, it realistically depicts the harshness and vulnerability of southern Louisiana poverty through the magical lens of imagination and a refreshing respect for folk wisdom. Except for the swelling orchestral music, which is at times annoying and at other times just plain manipulative, this movie is a real gem—philosophically, emotionally, and artistically.

Katrina marked a departure in America’s public image. With a majority of Hollywood films and television programs reinforcing images of American wealth and opportunity, the rest of the world garnered a well-franchised view of the American lifestyle. Indeed, the film industry helped depict America as a place of ridiculous affluence, especially from a developing world’s perspective. Until the levees broke in 2005, many foreigners assumed that we all lived like the characters of Friends or Dallas. It was a big surprise when images of the flood flashed through the air. Masses of unfortunate poor people—mostly black—were wading through putrid waters or sitting desperately marooned at the Superdome. It was an accidental, global realization: many Americans were poor and disenfranchised, too.

Katrina stories continue to emerge even years after the event. It swiftly became the major myth of our times, allowing us to confront many of our country’s hidden truths and identities.

Beasts, which has been called a Katrina allegory, is a particularly interesting contribution. Not strictly historical, nor bitter or preachy, the movie sheds light on the 2005 disaster by sharing intimate filmic studies of character and environment without an obligation to be factual. The collection of radical outsiders presented here live in a unique, isolated corner of the American geography, the wetlands of the Bayou. It is through traveling deeply into such borderlands—albeit in an armchair—that we begin to acknowledge and understand the mentality of life in the extreme hinterlands. These hinterland cultures co-exist and fester in so many corners of world.

The audience is inclined to sympathize with the beasts and rebels of Louisiana, despite their ignorance, violence, and drunkenness. It’s no accident that most scenes boast an intoxicating abundance of food and spirit: there are so many moments where delicious crabs and rich seafood pour out onto table tops and floors.

Never does anyone hand a waiter a plastic card. And despite the lack of traditional, bourgeois material wealth, the players’ wisdom and ability to live independently is impressive. Such resourcefulness is a wicked thing to practice in a contemporary world of floods, hurricanes, earthquakes, and worldwide economic instabilities. Is this the dystopic world into which we may digress? Or is this world outside the gates of mainstream culture actually a valuable, yet wild haven? Like the Native Americans that generously taught the pilgrims to survive their first winter in the states, are these the future tribes which will teach us to survive the next catastrophe?

The storyline focuses around a group of self-educated, party-loving, interracial survivalists living beyond the safe boundaries of the levee. This, of course, is a political notion: levees prevent the natural erosion of the land.

Make no mistake, these people do not feel excluded from the safety of the mainland. They prefer to live in a place destined to fill up with gulf waters. They playfully call their homeland the “Bathtub,” as if to demean any real danger. Said about those living on the other side of the levee: “They’re afraid of the water like babies.” This impending knowledge (and impending threat of nature), symbolized in the first half of the movie by a looming storm, is ever-present, feeding their fervor. Freedom is a treasure, and they’re willing to live with its consequences.

The main character, Hushpuppy (played by Quvenzhané Wallis), is born into this culture. She’s a young girl whose mother has disappeared and whose father is sick and worn out. She trumps around in dirty white rain boots and boy’s underwear. At first we may judge her father’s behavior as abusive, but ultimately see how he lovingly prepares his daughter for a life—a leadership role, in fact—outside the system. Alas, we march toward his death and the death of their homeland through Hushpuppy’s eyes. Will they both go down with the ship?

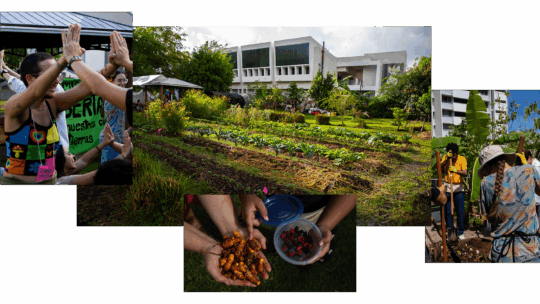

The sets are homemade wonderlands—floating arthouses with green roofs, trash paradises, jury-rigged inventions, and animals’ lounge yards. To live here is to be in tune with the environment, both industrial and natural. Hushpuppy is its product—tough and plucky and spiritually connected. Her father teaches her to grab and kill fish by hand. Dogs, chickens, and pigs are her close associates. “We are all meat,” she recites.

She attends class with the schoolteacher, a medicine woman who gives her herbs in a jar and lectures the children: “Gotta learn how to take care of people smaller and sweeter than you.” Mothering is rough, albeit wise, in the Bathtub. Many of the women seem to have already abandoned its territory (though, we find them later at the “Elysian Fields,” an amazing whorehouse that cruises the waterways). The female teacher figure seems to have what it takes to stay, and the implication is that Hushpuppy is her next lineage.

The director’s parents are folklorists, which is no surprise. Half anthropologists and half myth chasers, the filmmakers (Zeitlin worked with a collective called Court 13), lived for months on location in Montegut, Louisiana, using locals as actors. They allowed their fiction, which is fresh and quite sincere, to be infused with the juice of real, living context. This is not a film made by one man in power, but rather feels complex and organic like a well-harvested group project.

I could see how some who do not live in the South might misinterpret this film as promoting racial stereotypes. I do not see that here. Perhaps the dramatization of this lifestyle seems outrageous to anyone who’s never been to New Orleans. I would argue that although the characters are unrefined by globalized standards, their portrayal is not altogether negative. It seems the intention of the filmmakers is to glorify this endangered sect, while showing all the grit, too.

When poverty is romanticized on the big screen it is often through the cheesy haze of Hollywood. Plots are simplified, stars become saviors to two-dimensional savages, and things end happily. While Beast of the Southern Wild tries very hard to counterbalance the depressing aspects of the subject with grand music and whimsical parade-and-party scenes, it ultimately comes across with a strong political voice.