On August 27, the resurrected Atlanta Biennial, acronymically dubbed ATLBNL, opened to high expectations amid the larger Art Party, Atlanta Contemporary’s boisterous annual fundraiser. This iteration, the first in nine years, expanded to include the greater South, with works by 32 artists and collectives. It was organized by Contemporary curator Daniel Fuller, with ART PAPERS editor Victoria Camblin, independent curator Aaron Levi Garvey, and Gia Hamilton, director of the Joan Mitchell Center in New Orleans. We asked some attendees for their thoughts on the exhibition, the highs and lows, and what might be next for the irregular-ennial and art in the South.

Nathan Sharratt, artist

Survey exhibitions, like the ATLBNL, are reductive by nature. Which also means they’re not going to please everybody (nor should they), and they can’t include everybody (nor should they). Locals want more local artists. Regionals want more representation from their neck of the woods. Outsiders want to see the exhibition as a definitive statement of SOUTHERN ART. Many artists I’ve spoken with are just happy to be included in the validating in-group. As I was installing my work for the Studio Artist Wall in the week or so leading up to the opening, I had an interesting perspective of being near the ATLBNL, but not officially of it. This gave me an opportunity to walk around and spend time with the work as it was being installed, meet artists, and think about the perspective of being a Southern Artist (albeit a transplanted one).

For me, the ATLBNL is a beginning. It’s not perfect and it’s not comprehensive, but it begins (or continues) the process of announcing the South to be a relevant part of The Conversation. The work itself seems overall On-Trend and International Art Magazine-style, but with a Southern twist. Though for as much as the title of ATLBNL is so conveniently hashtaggable, there is a notable dearth of non-traditional, performance, or post-Internet work. It seems very rooted in history with, again, a Southern twist that assimilates the currently prevalent art languages of, for example, casualism and process-fetish. Southern art has, I think, struggled against isolationism and dismissal by the mainstream art world when we’re not being fetishized for our “rootsy exoticism” or “DIY pluck.”

Michelle Grabner wasn’t wrong when [at a public talk at Atlanta Contemporary in 2014] she said that the only way an Atlanta artist would be included in the Whitney Biennial is to have an Atlanta curator, but she wasn’t right, either. [Read our interview here.] We have the talent and vision to be a relevant part of The Conversation, we just need to assert our cultural authority with a louder voice, and, in my opinion, that’s what the ATLBNL is doing.

Anne Lambert Tracht, art consultant

I am always on the lookout for new talent from our region, so I am thrilled for the return of the Atlanta Biennial. For me, the exhibition was filled with many highs and lows, as any art biennial typically is. The highest high was Kalup Linzy’s wild family tree installation with videos that truly challenge ideas of family, society, and sexuality. Other highs were the giant wood hair picks by Darius Hill, the sculpture of Christina West, the figurative paintings of Ridley Howard, the immigration installation by Cosmo Whyte, the gold Black Lives Matter paintings by Stacy Lynn Waddell and the light piece by Phillip Andrew Lewis.

Alongside the highs, came the lows. There were many artists whose work left me wondering how the curators thought that this work was really the best the South has to offer. The exhibition seemed to lack cohesion, was overcrowded, and needed better (and larger) wall text. More information about the artists, as well as where they live, would have been a nice addition in order to give context to the work. Another nagging feeling that I had was that numerous artists had only recently moved to the South and were incorporated into the show for “star power” after achieving recognition in New York. Isn’t the mission of the Atlanta Biennial to give recognition to Southern artists who have not exhibited widely on a national level?

Matthew Terrell, freelance writer

The Atlanta Biennial pushed the Contemporary closer to what I think the public wants from that institution: more Southern artists and more themes relevant to local audiences. I hope the Contemporary will go forward from this exhibition more willing to show the work being done in our region, because I believe that will best serve the needs of our art community. My favorite pieces were Abigail Lucien’s interactive canopy pieces, as well as a perfectly rendered painting by Ridley Howard. One of the Contemporary’s ongoing challenges, which is evident in this show, is obtaining high-caliber work. There were graphite drawings and photographs in the Biennial that lacked the technical skills you would expect at this level. Overall, this show helped the Contemporary break away from notions of being a sterile space for out-of-touch artists. I hope they continue to become a more relevant space in our community.

Megan Murdie, freelance writer

As a “regional biennial,” the Atlanta Biennial sets out to elicit a contemporary Southern identity, one that represents the New South with Atlanta at its helm. Upon entering the exhibition, an undeniable disappointment washed over me when I saw Mary Proctor’s The Coming Supper, a Howard Finster-esque church pew painted in bright colors and covered with flat, churchgoing characters. Is clichéd, Southern “folk art” really representative of the New South? I think not, and after viewing the exhibition as a whole, it’s evident that the American South is about much more.

While Proctor’s The Coming Supper offers an example of the South’s folk roots, the rest of the biennial uproots stereotypes. Darius Hill’s What’s Your Jive Turkey and Sharon Norwood’s Things Fall Apart present us with a new Southern identity more focused on African American identity. Through their references to hair, Hill’s larger than life Afro picks and Norwood’s ceramic sink covered in shaven hair, the artists invite viewers to question what it means to be black in America, especially in the South. One work that questions the future of the New South is Stacy Lynn Waddell’s BLACK LIVES MATTER (Transformation). The work is a series of anagrams embossed on gold leaf: “black lives matter, bleek mattr aliv c, crak save little bm.”

On the whole, the Atlanta Biennial offers viewers a visual tour of where we’ve come from and where we’re going as Southerners. From Proctor’s church pew to Waddell’s golden hope for the future, the New South is about evolution and progress—and so is ATLBNL.

Christina Price Washington, artist

The ATLBNL has turned the space into something that appears to construct a representation of a stereotype of what Art From the South SHOULD look like. The exhibition participates in the production of the (Southern) stereotype, increasing the repertoire of Art From the South that contributes to the DIY image found in a flea market. The relationship of the work to the space feels insecure and compromised. Individual works of art cannot speak to each other; they are clustered in a display of some seemingly collective memory while the physical arrangements of works cancel each other entirely, covering up a few noteworthy pieces like Christina West’s Buffer.

Through charm, the South’s veiled politeness, it often delivers a sting. However, the South requires a special kind of sensibility because this lure only appears in a subliminal space. What an opportunity to fuse the complex relationship between Art and Art From the South! I think that Southerness must be carefully culled from the cultural landscape, and from that position ATLBNL missed the opportunity to interweave the subject Southerness as a cultural and intellectual engagement in the production of Art in the South.

Upon leaving the exhibition I noticed an empty Pabst Blue Ribbon beer can that was tossed in the vegetable patch at the entrance to the Contemporary. The vegetable patch contained only peppers that looked ready for harvest. Not sure whether this was part of the ATLBNL, I picked one little red pepper secretly and took a tiny lick where the pepper was broken while walking to my car. By the time I exited Means Street, my eyes watered from the pepper’s heat, holding my attention all the way home. If that was not part of the exhibition, it should (have) be(en).

It seems like everyone was excited to see the Atlanta Biennial return. Another smart move by the Atlanta Contemporary. My favorite thing was the ambition of the curators in taking on not only the Southeastern region but also in extending the boundaries past the traditional visual arts. I was not at all sure how Southern Food Ways Alliance was going to fit into this exhibition—and still a bit uncertain that it did—but where groups like this, Dust-to-Digital, and continent. began to challenge what I had expected to be included is where it became the most interesting to me.

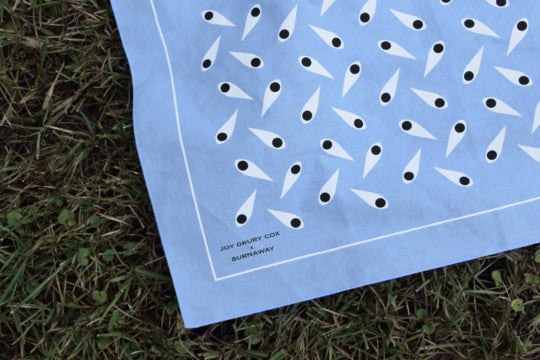

Susan Mackey, assistant to the director of the High Museum, and graduate of BURNAWAY’s Art Writers Mentorship Program

The opening of the ATLBNL was a veritable “who’s who” of the Atlanta art scene! Curators, writers, and plenty of grade-A bullshitters. There were cocktails. Hotdogs. Man buns! An art girl wearing head-to-toe blue tights, inexplicably sitting in an egg. Visitors getting ill-conceived tattoos on site. And, if you were lucky enough to catch it, some pretty stellar art as well.