In the 1960s and ’70s, the book as an artist’s medium gained a modest foothold in the contemporary art world. Appealing to artists of diverse sensibilities, the possibilities of the book as a space for artistic experimentation appeared limitless. This potential is borne out by the assortment of artists’ books in “Let’s Have Lunch: Selections from the ACA Library Artist’s Book Collection,” an exhibition on view at SCAD Atlanta through July 11, curated by Cay Sophie Rabinowitz, freelance critic and founder of OSMOS magazine, and Simon Castets, director of the Swiss Institute in New York. Including examples from Europe and the U.S., and mainly from the 1960s and ’70, the works in this exhibition offer a glimpse into the richness of the book medium and yet, by turn, inadvertently reveal its fatal flaw.

Rabinowitz and Castets chose food as the thematic focus of the exhibition based on their impression that it is a ubiquitous subject of artists’ books. Several of the examples here bear a straightforward, if at times humorous, relationship to the theme. Les Krims’s Making Chicken Soup (1972) consists of carefully staged, black-and-white photographs of the artist’s mother, unabashedly dressed only in her panties, preparing ingredients for a batch of soup. Taking even greater advantage of the intrinsic serial structure of the book, Kenneth Josephson’s quirky little Bread Book (1973) is a photographic “portrait” of a loaf of bread, each page corresponding to a single slice. Eschewing images in favor simply of text, Al Hansen’s Lettuce Manifesto is word poem doubling as a Fluxus manifesto, each line of which exploits the homophones “lettuce” and “let us.” Hansen’s opening declaration, “Lettuce bring art back into life,” could just as well be a characterization of the book itself: a portable, inexpensive, and mass-produced object all but stripped of high art pretensions.

The exhibition includes several of Ed Ruscha’s books from the 1960s and early 1970s. Though their relationship to the curatorial theme seems tangential at best, they are nonetheless paradigmatic of the medium. They remain distinctive for their cover typography and the deadpan, serial cataloguing of images of objects and locations in and around Los Angeles. One of the artist’s most innovative books, Every Building on the Sunset Strip (1966) presents continuous views of the buildings lining both sides of a section of the Strip. Unfolding accordion-style to a length of 25 feet, the structure of Ruscha’s book neatly mirrors its content.

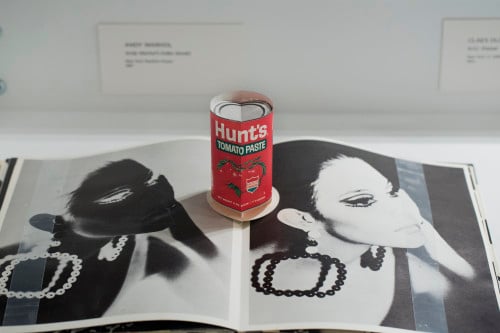

Andy Warhol’s Index (Book), 1967, also demonstrates an innovative use of the book format, in this instance the inclusion of pop-ups and fold-out structures, of the kind more typical of illustrated children’s books. As a compilation of interviews, images, and project notes, Warhol’s book likewise points to another popular function of the medium, namely as a space for chronicling artistic activities and ideas. This is the premise behind two related works by Philip Corner and Alison Knowles. Inspired by her practice of ordering an identical lunch every day—a tuna fish sandwich and a glass of buttermilk or cup of soup—Corner joined Knowles at Riss diner in Chelsea and, by contrast, chose to sample everything on the menu. He recorded the experience in Identical Lunch (1973). Knowles also invited others to join her lunch ritual, accounts of which she compiled in The Journal of the Identical Lunch (1971).

The exchange between Corner and Knowles illustrates how food, the exhibition’s theme, points to broader concepts, including the importance of paying attention to the seemingly small details of everyday life and, concomitantly, of fostering conversations and relationships based on those details. In this regard, food-related activities conjure up the conviviality of the artistic networks in which artists’ books from this period were frequently conceived and circulated: here, the communal spaces of kitchens, restaurants, bars, and city streets assume a greater presence than the isolated artist’s studio.

While the works of Knowles and Corner celebrate the populist nature of such social spaces, others in the SCAD exhibition adopt a more satirical stance toward the art world network. For instance, Les Levine’s After Art: Museum of Mott Art, Inc. (1974) is a mock catalogue of services available for purchase through the artist’s imaginary company, including “Language Services for Painters,” “Art Supplies for Filmmakers,” and, even, “How to Stop Being an Artist” and “How to Kill Yourself.” As a parody of an artistic “survival guide,” Levine’s book nonetheless takes a pragmatic look at the stark realities of the art professional.

Artist’s books lend themselves to reproducibility and portability. Many artists have taken advantage of these qualities in order to bypass traditional modes of artistic production, distribution, and display. Just as significantly, books’ recipients are supposed to hold and handle them. Ruscha understood this aspect of the medium when he chose to publish unsigned and unlimited editions. He wanted to undercut the customary aura of the work of art, and to some degree he succeeded: one can just as easily find his books in public libraries as in museum collections. This is not the case, however, with the majority of artists’ books. Instead, and as the SCAD exhibition demonstrates, most of them are no longer publically (or physically) accessible. Valued as “art,” they are now, understandably, preserved and protected in museum display cases. Nonetheless, this does a great disservice to them and, further, makes for a less-than-satisfactory exhibition experience.

Rabinowitz and Castets tried to compensate for this limitation by creating a wall display—a collage, really—of reproductions of individual pages from some of the selected works. This allowed visitors a partial glimpse into the actual content of the books elsewhere ensconced behind glass, but since the pages were stripped from the serial structure of the works, it proved confusing at best. Though it is perhaps unavoidable, the exhibition ultimately illuminates the disconnection between the format of the traditional museum and that of the book medium. Unfortunately, it is the latter that tends to suffer as a consequence.

Susan Richmond is an associate professor of art history in the Welch School of Art & Design at Georgia State University.