There is clear resonance between the two bodies of work featured in the Swan Coach House Gallery’s exhibition, “Systems.” Unexpected color and textural combinations in organically arranged compositions by Amie Esslinger and Lauren Michelle Peterson are visually harmonious, at least at first glance. Along with this visual correspondence, the exhibition’s strength lies in the set of comparisons it offers between this pair of Atlanta artists: Despite initial formal similarities, their processes, concepts, and experience levels vary, in some senses, to extremes of total polarity.

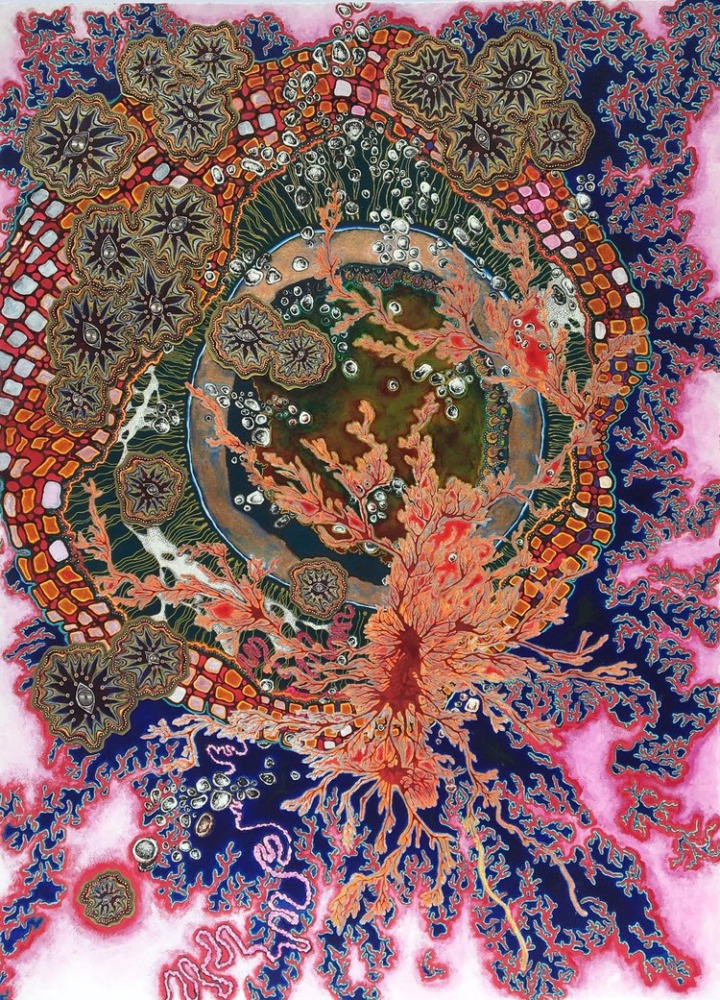

In stark contrast to the dozens of exhibitions listed on Peterson’s CV, Esslinger’s exhibition history is brief. Esslinger engages biological forms, what one might label the “natural,” while Peterson constructs archaeologies of human consumption composed largely of “unnatural” materials. Peterson’s woven grids and happenstance, sculptural arrangements of found objects are clear quotations of the modernist plane, the readymade, collage aesthetics, and other key art historical developments of the last hundred years. Esslinger’s distinct style of mimicking microscopic structures by stacking painted paper evidences sharp instincts and makes her art easily recognizable. Her sensibilities for color and composition establish parity between the artists, regardless of their exhibition histories.

Suspending critical evaluation for the moment, the projects’ visual similarities belie radical differences in approach and concept. Referential as Peterson’s configurations of detritus are, they indicate a sense of arbitrariness, like an aloof “couldn’t care less that this is in a gallery” attitude. Esslinger’s carefully layered cut paper, balsa wood, and other media impart an opposite visual tone, so stylistically distinct, marketable, and meticulous, it’s easy to visualize Esslinger’s art complementing the decor of a stylish living room or lobby. Even Peterson’s woven cardboard grids, probably her most salable works, aren’t as commercially viable.

“Salability,” said Peterson, “seems to be about the result and about achieving something,” as in some imaginary fixed ideal, “and if it doesn’t satisfy, it’s deemed worthless.” She placed a clipboard with her price list to a wall amid collected litter, like a cheeky reminder that selling art is just another social activity, or a ritual with its own set of relative rules. Her art in sum critiques functional hierarchies by accumulating objects that can no longer be described in terms of use, but rather are reduced to their material facts.

To her, “there is no trash,” and neither she nor any artist are in any position to redeem supposedly valueless stuff. “If I take something into my possession, why does that elevate it?,” she says. “Who am I that I would have such influence?” It’s obvious, however, that the objects she collects can’t simply be reduced to material facts. Even if her intervention aims at dismantling hierarchies of value, her artful acts indeed create value from the valueless.

Envisioning how these artworks are produced invokes just how radically their fabrication processes diverge. On the one hand, one imagines Peterson arranging random items she’s found in various unremarkable places, until an unconscious moment arises in which everything feels in place. On the other hand is Esslinger, fastidiously experimenting with colored cutouts surrounded by biology textbooks, microscope slides, and jarred specimens. (“I’m not disciplined enough to sit in a biology class anymore,” she said in jest, “but I want to steal the slides and run!”) These tensions compel the question of what exactly draws their practices together, from a curatorial standpoint, other than consistencies in color and form, and other than the fact that the artists are women living in Atlanta. Isn’t there some sense that these works contradict each other, or at least have altogether dissimilar aims?

According to curator Marianne Lambert’s exhibition statement, these “similar yet contrasting” projects “create networks based on our natural and social worlds,” and acknowledge “an order that accepts chaos, subjectivity, and uncertainty.” But how do the artists define natural and social networks, and what are their categorical boundaries? How does pairing these particular artists tell the story of an order that accepts chaos, and why is this an apt description for this specific exhibition? What does the word “system” mean to these artists?

Peterson explained to me that a system “is a set of rules – all activity of the system is contained within the boundaries generated by the rules.” These rules are “fluctuating, subjective,” and by “poking at the determinacy of the rules from the outset,” she looks for the “edge” where use and value break down: Far from absolutes, use and value are merely arbitrary ways of organizing material properties.

Esslinger told me she’s also interested in rules and relativity. “Experimenting with color and material,” she creates “formulas” that guide “the factory work of cutting, painting, cutting, gluing.” Chance disruptions, like “slips of the brush or pen and random efforts,” keep the work consistent “with how our natural world actually functions.”

Esslinger and Peterson both deal with function. From the perspective of evolutionary biology, a chance mutation is advantageous if it helps an organism to reproduce in a given environment. Since the organism is more likely to reproduce, the trait is more likely to be passed onto subsequent generations. So too, a social behavior or meme that self-replicates via imitation, or “likes” and “shares,” interacts with particular environmental conditions, and its propagation depends on how well it functions in those conditions. This functionalism, as Peterson and Esslinger both illustrate, depends on whether or not something works in a given setting, not on some preexisting ideal or apex.

“While I was installing there came a moment,” said Peterson, “when everything felt right in-situ, that it was the farthest I needed to go – because there is no ideal. I see everything as in process.” Esslinger, echoes this feel for process. Modeling her practice after natural selection, she’s always been “enamored by the visuals of microbiology and tiny life forms.” Growing up, she passed time exploring creeks and forests on her family’s plot of northeast Georgia wilderness, “which provided ample plant life and gooey creatures to touch, pick, and scrape.”

Both artists, then, see themselves and their practices as parts of social and natural systems. They reveal that the boundary between natural and unnatural, between what’s nature and what’s human, is unclear, or even nonexistent. Their works in tandem issue a thoughtful conversation on how systems function at micro and macro scales. A strange balance of rules and relativity governs the tiny, cellular structures Esslinger mimics and the social artifacts Peterson archives; both seek to represent this strange balance.

“Systems” is on view at the Swan Coach House in Atlanta through September 23. An artist talk will take place at the gallery at 3pm on September 10.

Jared Butler is an Atlanta-based critic.