“Alternative Modernisms” at the Southeastern Center for Contemporary Art (SECCA) is a generative show. The exhibition title alone speaks to the possibility of fluid meanings – Modernism set forth in the plural insists on a multiplicity and a refusal of the monolithic art-historical, capital-M construction of modernism. The title further suggests that modernism is not a function of the past but rather that it persists in a state of flux, filtered through an array of alternating viewpoints – less temporally/historically static than “postmodernism,” a term that (much like other categorical appellations, such as “trans-racial”) always felt more aspirational than accurate.

The exhibition, on view through August 16, brings together five artists whose work calls into question the nature and function of representation through a range of image production strategies. The diverse practices of Harun Farocki (1944-2014, Berlin), Leslie Hewitt (NYC), Pedro Lasch (Durham, NC / NYC), Jumana Manna (Berlin), and Jeff Whetstone (Durham, NC) give rise to photographs of photographs, photographs of subjects who self-consciously represent for the camera, photographs of paintings, filmed paintings of objects and objects being photographed, and fictive cinema inspired by archival photography. In each case, there is an undercurrent of the anthropological and a self-conscious approach to artmaking as evidence of human cultural production.

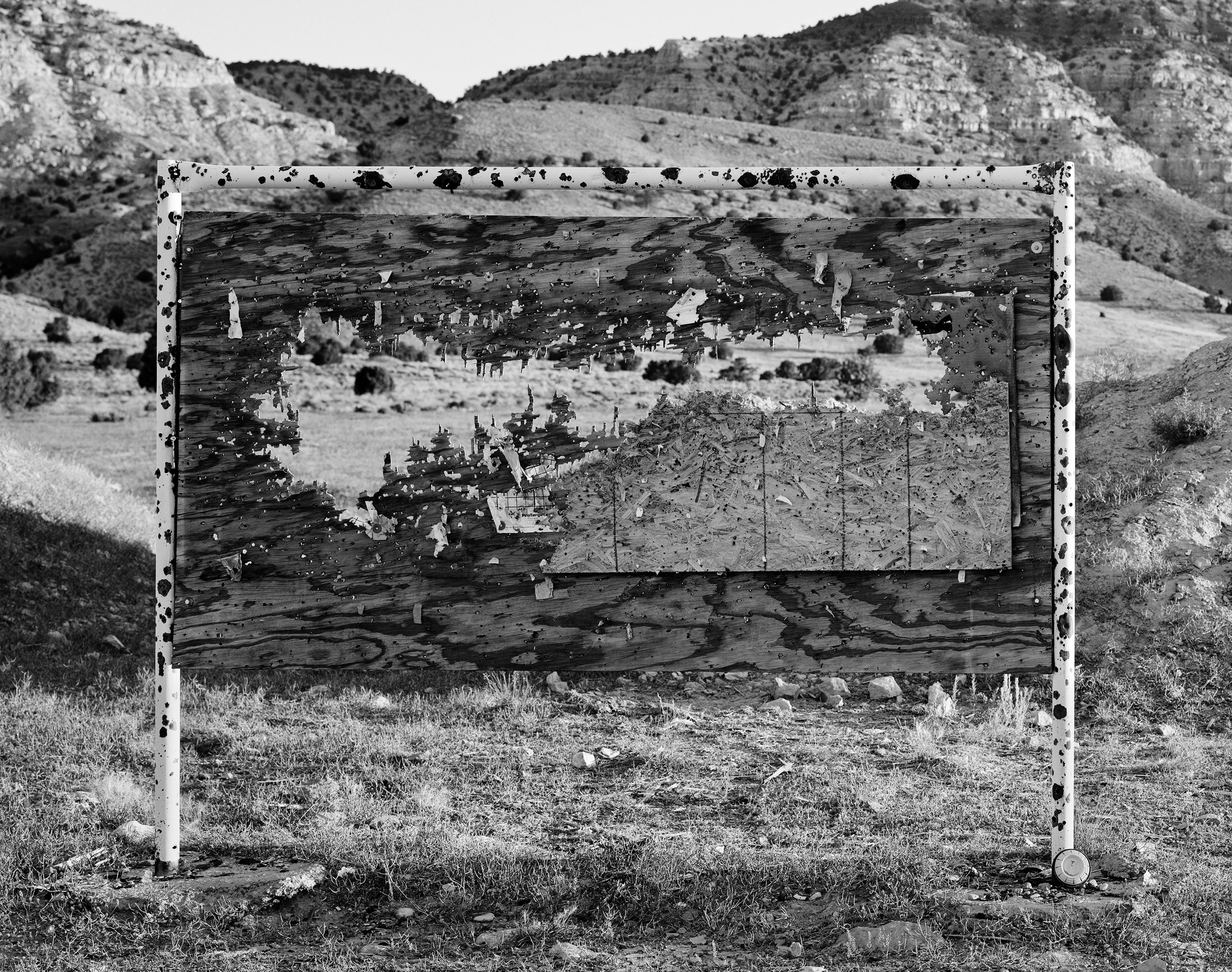

Jeff Whetstone’s indexical photographic practice locates a particular strain of the outdoorsmanship culture of the American South. Hunter/protagonists bedecked in full camouflage regalia populate as-yet undeveloped zones of the planet, spaces that have been designated as “wild.” The images trouble such designations, with scenes in which fully armed subjects, in algorithmic oscillations, come across as both other than and integral to the so-called natural environment.

Venus and Mars (2014), a larger-than-life photomural – Whetstone’s only color work in the exhibition – frames two seated figures in a wooded setting, two women fully shrouded in hand-crocheted camo panchos. Their firearms are like prosthetics, extensions of self. The immersive image brings us into their world and provides a sense of intimacy. As with many of Whetstone’s portraits, the figures gaze at us directly, unflinchingly, paradoxes of confrontation and access.

Whetstone’s photographs are complemented by a video projection, Drawing E. Obsoleta (2011). Shot from above by a stationary camera, the grainy 16mm black-and-white film tracks the movements of a black snake against a white ground manipulated by a hand wielding a stick. The snake winds and whips, morphing fluidly into drawing, symbol, glyph, and icon. The action occurs on a leaf-strewn forest floor in both daylight and into the black of night. The writhing is fearsome, mesmerizing, bone chilling. On one hand, the work invokes Pentecostal snake handling, on the other, the unwritten history of mark making, a material embodiment of the idea of the tabula rasa.

Whetstone’s interrogations of hunting culture in the American South, with its specific constructs of nature and “the natural,” are offset and further complicated by Pedro Lasch’s What are we before we are naturalized? Citizenship, Portraiture and Abstraction – a performative photographic project that challenges the social and political condition whereby “nature” is transitioned from noun to verb.

The work takes the form of large color digital prints that document performative interventions in museums and other cultural/institutional spaces. The images memorialize a process by which visitors to these spaces (the Smithsonian, the National Gallery, the Hirshhorn, etc.) are outfitted with mirrored masks, flat rectangular forms with three machined orifices, two for the eyes and one for the mouth, isolated loci of sight and language.

The material conflation of two loaded forms — the mask that is also a mirror, the mirror that is also a mask — is a construct that works overtime churning out multiple meanings, bouncing meanings off the walls, a kaleidescopic index of cultural/historical complexity. This construct (punningly) mirrors the temporal destabilization underpinning the idea of “Alternative Modernisms,” the idea that cultural “moments” persist and wash across historical space in waves. Case in point, the image of Lasch’s mirror-masked participants, anonymous bodies variously reflecting old master portraits, traditional landscapes, and Jackson Pollock splatters brought to mind “They Became What They Beheld,” Edmund Carpenter and Ken Heyman’s MacLuhan-inspired 1970 monograph. A subversion of both portraiture and self-identity, What are we before we are naturalized? trafficks in the reflective fragmentation of major artworks, displaced and superimposed upon the suppressed visages of its participants. Another 1970s echo here is Robert Altman’s Images (1972), in which the approach of the self, the encroaching self-as-other, culminates in an encounter with self as a source of horror and madness: the metaphor inherent in the mirror is a schizophrenic one. Lasch’s work further functions as institutional critique, reflecting the space of the museum back to itself.