Children are often disturbingly unclear on exactly which aspects of the world are real. This isn’t surprising, since in a way they are aliens, arriving on earth with no knowledge of our language and customs. In “This Message Has No Content,” P. Seth Thompson considers how the fantasy images that we bathe in as children continue to shadow and light up our vision.

Thompson’s large digital prints feature Photoshopped movie stills or lines of dialogue taken from science fiction and fantasy films of the ’80s: The NeverEnding Story, Labyrinth, Goonies, Splash, Space Camp, *batteries not included. If you saw these in the theater as a kid, odds are that you have affection for them wildly out of proportion to their quality. The ideal audience for these works, then, is probably viewers of a certain age capable of experiencing the small thrill of recognizing where each shot, title, and snippet of text comes from.

A danger of this sort of appropriative project is that the images may not stand up on their own once extracted from their surrounding web of cultural references. Heavily quotational works can coast along on a gooey wave of sentimentality and nostalgia rather than reaching for any more emotionally challenging engagement. The challenge is making repurposed images go beyond what is contained in their source material so that they don’t become “messages without content.”

Thompson meets this challenge by striving both visually and conceptually to convey a sense of inhuman or unearthly sight, a process he has described as part of his search for an “alien aesthetic.” This is captured in the current exhibition by two recurring formal motifs. One is a diagonal crosshatch pattern that takes on subtly different forms, alternately becoming thick woven fabric, melted circuit board, or intersecting crystalline planes. Another is a bas relief-like shallowness, which makes the gruesome teenage astronauts in Time Coincidence Module (2014) appear embossed on discolored metal, and Daryl Hannah’s profile in Yesterday’s Impossibilities Become A Part of Everyday Life (2014) rise like scraps of red cloth from the surrounding void.

archival pigment print, 30 by 60 inches.

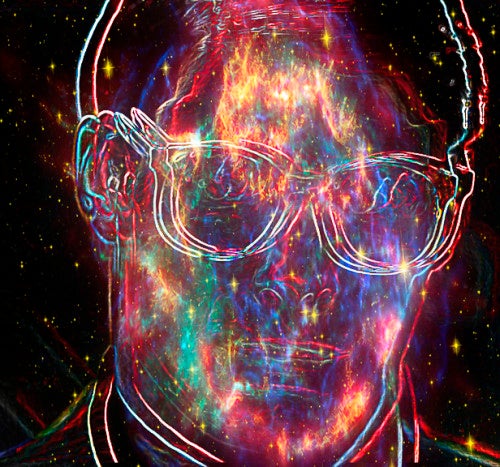

If aliens perceived humans as anything at all, it might be as these discolored, flattened lattices of light. In one of the strongest pieces in the show, The Self Made Man (Christopher Reeve as Clark Kent as Superman), 2013, Thompson depicts Kal-El as a neon silhouette lit up by a blazing nebula, driving home the fact that his human identity is just a thin wrapper around a living solar battery. Alien seeing is central to the Superman mythos, according to which his Kryptonian eyesight possesses endless reach and resolution, making merely terrestrial things seem flimsy and diaphanous.

Themes of sight and concealment also feature in the sharp image-text piece I’ve Got One That Can See (2013), which quotes a famous line from They Live, John Carpenter’s science fiction allegory about penetrating the illusions of capitalist society. Beneath the text lies the digitally smeared face of Janet Leigh in Psycho, and the two make an appropriate pair: poor Marion Crane might have survived if she had been able to see through Norman Bates’s mask of sanity. The four purely text-based works are significantly weaker, however, since they feel more like titles in search of images, didactic cues rather than visual explorations of these ideas.

Thompson’s films of choice often deal with shedding and overcoming illusions. But these works acknowledge that this process is a mixed blessing. The human perspective is tacitly that of the grown-up adult; children, like aliens, mermaids, and mythical creatures, are outsiders. As we become human and our childhood wishes and fantasies drain away, so too does our alien eyesight.

“This Message Has No Content” is on view at Sandler Hudson Gallery through November 1.

Dan Weiskopf is an associate professor of philosophy and an associate faculty member in the Neuroscience Institute at Georgia State University. He is the author, with Fred Adams, of An Introduction to the Philosophy of Psychology, forthcoming from Cambridge University Press.