It’s 1989 and Anna, an assistant working her way up the ranks of a Black culture television station, is considering getting a sew-in weave for the first time. Pressured by her higher-ups and colleges to look the part of a modern and sophisticated host fit for airtime, Anna trades her natural hair for a cursed weave with a lust for blood in Bad Hair (dir. Justin Simien, 2020). Having seen the horror/comedy film at Starlight Drive-In the evening before visiting the gallery, I imagined that I had somehow entered an extension of the film’s campy visual effects as the walls of Camayuhs oozed and glowed around me. Alexis Childress’ The Tekhnologia of Blackness examines the same horrors displayed in the film, that of catering one’s identity to white standards for consumption.

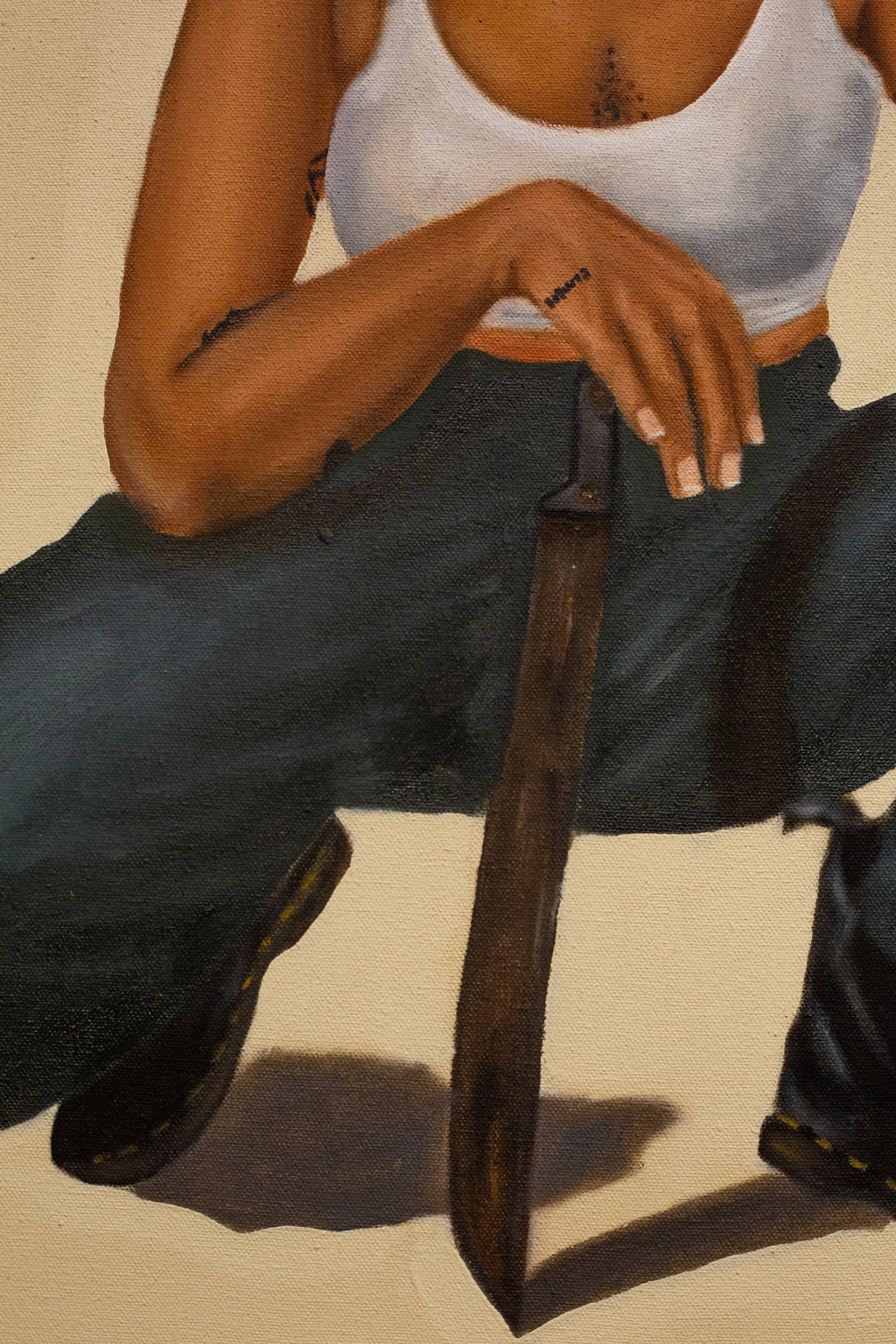

Tekhnologia, a Greek word meaning “systematic treatment,” asks us to consider how we approach the images before us as Childress reimagines the Black body. In large photographic prints, portions of disjointed figures are isolated and flattened, interrupted by digitally drawn lines that appear to sew lips closed, while other interruptions poke holes in body parts or ooze slime down a headless neck. Along one wall of the gallery, legs and arms twist into a crabwalk. In another image, a pair of closed eyes ooze and are pierced by a long white line, causing me to shudder at the thought of a needle in my own eye. These clever embellishments are reminiscent of the surreal imagery of the film I’d seen the night before. What Childress displays, however, is not an insidious drive toward respectability but rather a blunt opposition to imposed paths of white standards or expectations.

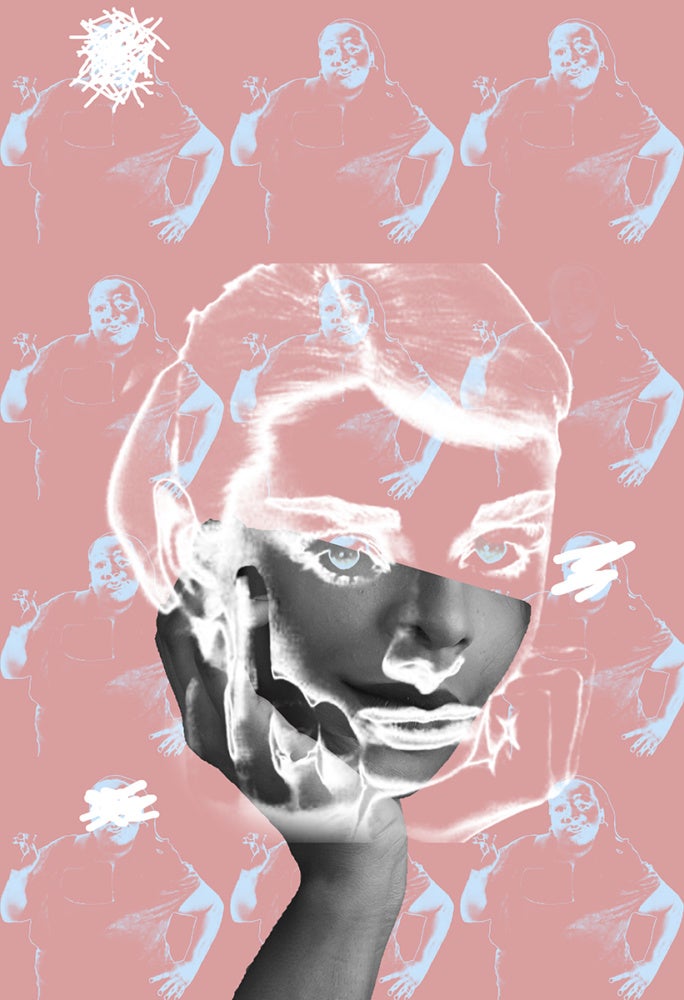

A large and visually captivating pink wallpaper of collaged images envelops half of the gallery. The background shows a grid composed of meme-ified images of a “sassy Black woman” posing with one hand on her hip and the other outstretched, wagging in the air, lips pursed and ready to tell you off. Several images of her are rubbed out by an eraser tool, while a large image of a flippant white lady stares outward and casually flips you off. She even appears to half smile, as though acknowledging the sinister power she holds. Aptly titled Sassy Black Woman Vs Sassy White Woman, the installation pointedly displays the amount of disengagement a white woman can have and still be seen and heard while a Black woman who is vocal and engaging may just be rubbed out by the eraser tool.

Stepping into the other half of the gallery, there is a stark shift toward realism. The imagery is no longer flattened onto solid colored backgrounds. Instead, busy collages and a hundred faces are pressed into one composition. The New Nadir (Google Image Search: Black People Police) collages images of Black protesters being thrown and held to the ground, restrained and dragged away. This imagery is immediately recognizable from a summer spent in the streets demanding justice and reform from a failing and racist system. The dense miasma of images mimic screen prints as image overlays cause things to posterize or disappear. Another image, I Would Die for Straight Hair, depicts a headless woman, oozing from the neck, holding an enlarged head between her thighs while pulling on the long straightened hair. Images of common beauty supply relaxers and oils pixilate the background. As Blackness is continually commodified and consumed by white audiences and degraded to meme and parody, Childress codes a new visual language for self-defined identity. While seemingly everyone wants to don the charisma and cultural signifiers of Blackness, no one desires the pain of being Black in America. As Frank B. Wilderson III notes, “There’s something organic to Blackness that makes it essential to the construction of civil society. But there’s also something organic to Blackness that pretends the destruction of civil society.” In her exhibition, Childress appends new definitions of Blackness for the present and future while carving a path towards greater legacy and understanding.

Disclaimer: Camayuhs founder Jamie Steele is a member of Burnaway’s board. Editorial decisions on coverage and consideration are made completely independently of advertising or board relationships.