“Southerness” is a concept that has been broached by a variety of writers and artists over the last few years. Alec Soth takes his shot in the show, Georgia Dispatch, on view at SCAD’s Gallery 1600 through January 20. The 19 black-and-white images create a suite of photographic artifacts from Soth’s epic excursion through the often unseen and unnoticed nooks and crannies of the state. The images on view are part of the seventh and final issue of Soth’s “irregularly published newspaper” The LBM Dispatch.

Nearly five years ago, Soth called up his buddy and writer Brad Zellar with this idea of pretending to be small-town reporters chasing oddball stories just outside of their hometown, Minneapolis. They created a fictitious newspaper, The LBM Dispatch, and business cards to make it seem legitimate. Then, the idea that started out as something to do just for kicks-and-giggles mushroomed into a much bigger project with six other editions, each with its own flavor focused on six other states: California, Colorado, Michigan, New York, Ohio, and Texas.

Most viewers might assume that, given their origin, these images focus on the societal outliers that make for an interesting read in any local gazette. However, Soth, the quintessential interloper, creates for us a view of Georgia that goes deeper than the superficial and absurd. In some ways, the photographs are pathetic and unsettling. These feelings abound because Soth forces us to think more deeply, to see the images perhaps as representations of unspoken and sometimes unflattering truths about this state, difficult to view and even more difficult to acknowledge. A native might ask, “How could an outsider be so impolite as to expose the economic disparity, racial tensions, and other struggles that few local citizens discuss?”

Near Gainesville, Georgia (all works 2014), the largest of the archival pigment prints at 54 by 72 inches, greets visitors at the exhibition entrance. In the foreground, the base of a hill is covered in kudzu. Near the top of the hill is an abandoned white clapboard house about two-thirds engulfed in the kudzu as well. There are trees behind the house not yet choked off by the fast growing vine. It is daylight, but there is no sunshine, only thick gray and white clouds. Does the kudzu overtaking the abandoned house signify the abandonment of the American Dream? Given the calamitous recession and astronomical number of foreclosures in the state, many Georgians have had to relinquish that dream and worse, that reality.

Two other photographs broach the Confederate past of the state. In Charles Roark, Chickamauga, a gray, bearded, 71-year-old Roark is lying on a quilt covered bed. He’s dressed in a Confederate uniform with hands folded on his stomach and legs crossed at his ankles. The walls of the room are covered with dark paneling from the ’60s. Mr. Roark seems to be asleep. While many around the country think that the Confederacy is dead, the gentleman dressed in his uniform symbolizes an attitude that is still alive and well. Wildman’s Civil War Surplus, Kennesaw makes one look closely to determine whether the soldier wearing a hat matted with dust and cobwebs is a man or a mannequin, further reinforcing Soth’s revelation that Georgians still live quite dichotomously in both the old and new South.

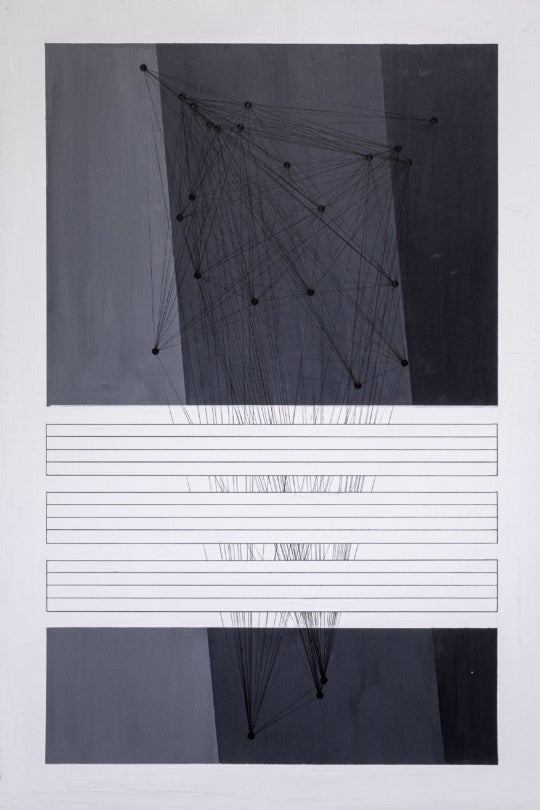

In Southeast Augusta, the shot is of a predominantly black neighborhood in Augusta. One sees a half dozen nearly identical shotgun houses with tin roofs rusting, paint peeling, and porch railings sometimes loose and rickety. Several are boarded up. The shotgun house is a significant marker in Southern history, common to many poor and black neighborhoods. Other artists, such as Beverly Buchanan, have made these houses central to their work. Even more interesting in this photograph is the way in which Soth has captured the telephone and electrical lines connected to the houses. They rise up at an angle across the top half of the image, like the strings and wires that control a marionette. Is Soth telling another story? If the inhabitants of these homes were puppets, who would the puppeteers have been?

In Mrs. John Beauchamp Coppedge and Mrs. Duddley Ottey, Sr., Piedmont Driving Club. Atlanta, Soth broaches the subject of old mores and “old money.” In the scene, two women with dour expressions and silver hair pose standing inside the exclusive social club. The title is revealing. Their first names are unknown and presumably unimportant, perhaps a comment on how the South has traditionally viewed women.

Soth, a member of the prestigious Magnum Photos, is well known for his documentary-style images that capture provocative and heartfelt stories about our changing society. From this exhibition, it seems that Soth’s story about Georgia is that not much has changed. Regardless, whether you agree or disagree with him, if you’re into art that makes you think, I’d highly recommend you stop in. If you enjoy beautifully shot photographs that engage because of their formal qualities, Soth delivers this too.

Greg Head is an Atlanta-based writer and cultural anthropologist. He is also managing partner at SmartThink Marketing Group, a research and marketing strategy consultancy, and a BURNAWAY board member.