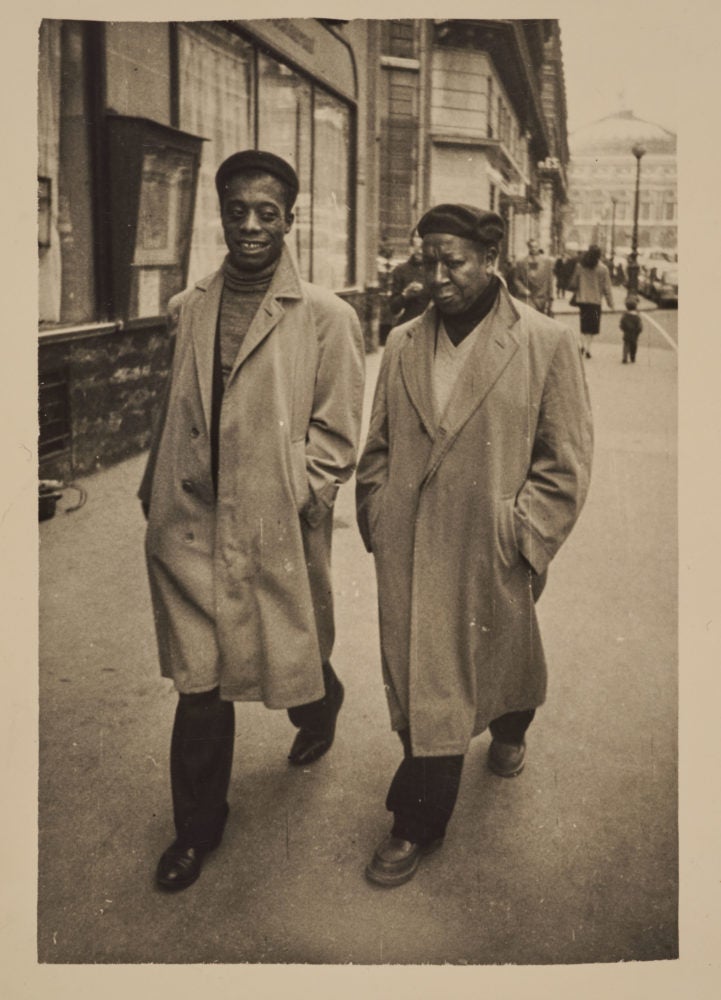

In 1940, a young Black man—hardly more than a boy—arrived at 181 Greene Street in Greenwich Village, the location of the third-floor studio of the painter Beauford Delaney. Delaney, already a nationally respected artist, opened his door, inaugurating a thirty-eight-year friendship that would stir the spirits and nourish the creative souls of both parties across a lifetime.

That curious fifteen-year old was the writer James Baldwin, calling upon the much older Delaney on the recommendation of a mutual friend. The Knoxville Museum of Art takes the title for its new exhibition, Beauford Delaney and James Baldwin: Through the Unusual Door, from Baldwin’s description of that initial encounter, published in 1985 in the essay collection The Price of the Ticket: “Lord, I was to hear Beauford sing, later, and for many years, open the unusual door…”

The door makes an apt symbol for the transformations Baldwin and Delaney wrought upon one other. They were naturally kindred in many ways: both sons of ministers, both visionaries, both gay Black men determined to thrive in racist, unequal societies set upon their destruction. They came from poor backgrounds in areas of racial tension—Baldwin from Harlem, Delaney from Knoxville (thus the location of the exhibition). The latter made his way to New York by way of art school in Boston, where he also gleaned an education in radical Black politics and ideas, lessons Baldwin would go on to augment considerably with his own activism.

Through the Unusual Door seeks to present Delaney’s work in the context of the bidirectional influences of that artistic and intellectual connection. Delaney became for Baldwin a mentor and father figure; Baldwin turned Delaney on to his intellectual touchstones and participation in the civil rights movement. Baldwin said he found in Delaney “the first living, walking proof…that a black man could be an artist”—that he taught Baldwin nothing less than “how to see.” In a 1984 interview, Baldwin recalled walking the streets of the Village with Delaney, who pointed down to an oily puddle, saying only, “Look.” Baldwin realized he could see all the lights and colors of the city in the puddle’s iridescence, and in that moment, learned to trust his sight.

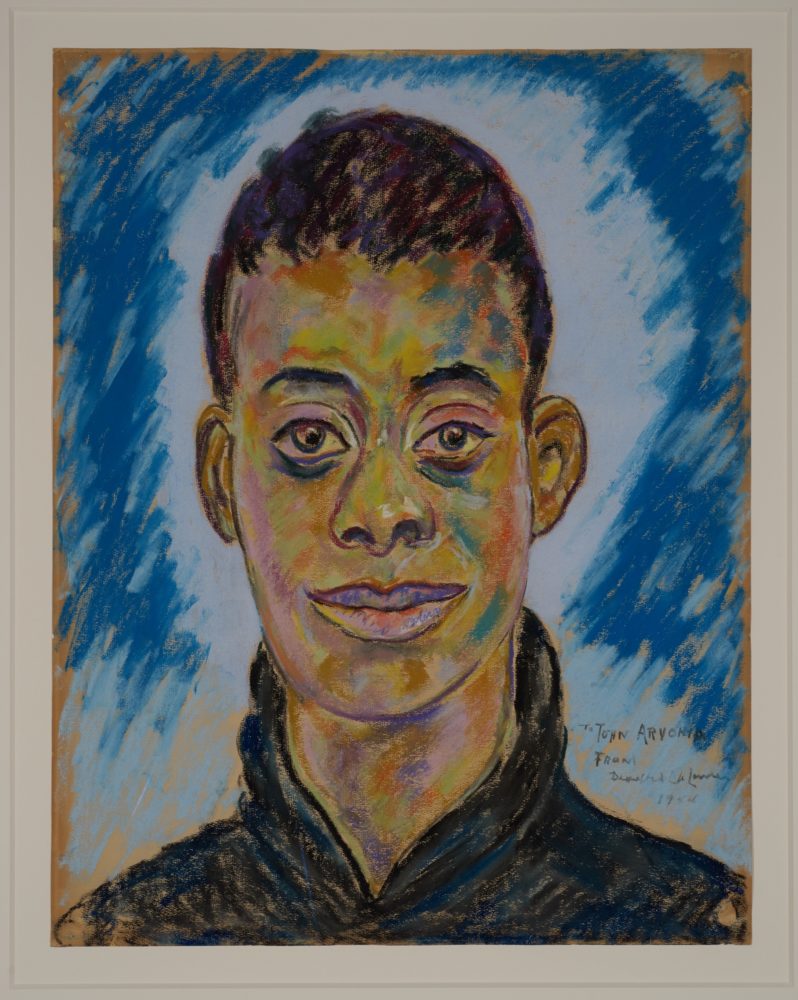

That image may be said to embody Delaney’s fundamental artistic concerns: light and movement, exemplified by his 1946 painting Greene Street, which depicts city structures in textural, vibrant shapes and strokes, as a collage of light and color fragments. An untitledpaintingfrom just a year later makes use of similarly expressive brushwork and a saturated color palette but delves further into abstraction, prefiguring the nonrepresentational work that would come to dominate Delaney’s oeuvre as his career progressed. The exhibition also features a short film, Abstract in Concrete by John Arvonio, which captures the shimmering reflections of Manhattan lights in the wet pavement; critics theorize Delaney may have seen preliminary footage and incorporated it into his work. Whether he did or not, the video’s inclusion is a smart choice; it makes more immediate Delaney’s preoccupation with movement in an otherwise relatively static environment.

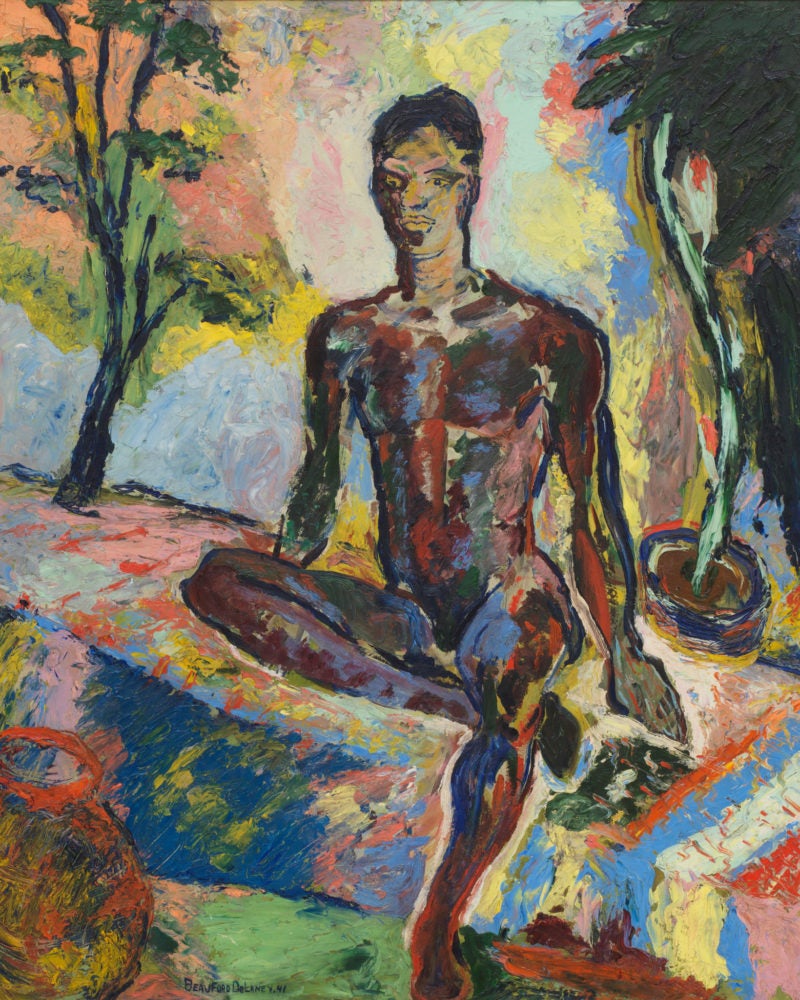

As Delaney’s friendship with Baldwin deepened, his art became more expressive, less confined by naturalistic formalisms. Delaney painted more than a dozen works depicting, inspired by, or dedicated to Baldwin, including the well-known portrait in pastel from 1944. The bold hues of Baldwin’s face echo the vision of Arvonio’s film. The subject appears confident, knowing, handsome; the viewer meets a direct gaze from his signature bedroom eyes. The royal blue-rimmed halo around his head evokes a sort of higher status, an elevation to a plane above the ordinary.

The striking, vivid nature of Delaney’s Baldwin portraits brings to life Baldwin’s extraordinary persona, unparalleled intellect, and preeminent place in American history. The 1957 work James Baldwin strays even further into expressionism, comprising a full-body Baldwin made of bright yellows and blues, heavily outlined in a style reminiscent of Vincent van Gogh. He hovers in front of a joyful quilt-like background of pastel cobalts, teals, and yellows. Delaney reconciled the tension between his representational and abstract tendencies by framing all his work as “studies in light revealed.”

The same cannot be said as easily of the painter’s own self-portraits. These pieces, grimmer in tone and expression, would seem to reflect Delaney’s lifelong mental turmoil; not only did he face the discriminatory violence of white Western patriarchy in an economic depression and at war, but he also suffered from chronic depression and loneliness. He depicts himself stern-faced, cigarette in mouth, impassive to the penetrating eye, unmoved by his own gift. These paintings are perhaps “expressive” in the more modern sense: reflective of Delaney’s inner subjectivity, less idealized, infinitely complex.

Wanting to protect Delaney from the darkness within and without, and urging him closer to the fashionable contemporary art world, Baldwin encouraged Delaney to attend the artist retreat Yaddo, and to move to Paris in 1953. After only two years there, Delaney moved to the quieter suburb of Clamart, where he could tend to his afflictions in peace, and where his work reached its pinnacle of abstraction. There, his single window to the outside became his portal to the world; through it he saw the full range of light and color, unlimited by geography. He began incorporating new materials such as sand and powdered pigments into his works, and his heretofore contained shapes loosened into loops, swirls, textures, and layers that achieved a dazzling breadth and depth of tone akin to that of the artists of the fifteenth-century Northern Renaissance, who piled pigment upon pigment to create jewels and globes.

In this era, Delaney largely dispensed with realism, taking up an almost religious preoccupation with color. He said that, as a child, he found himself lying awake all night, unable to sleep, because his red bedspread excited him so much. Much of his work from the late 1950s and 60s represents studies in the movement of brush across canvas. These large-scale works appear monochromatic from a distant glance but reveal themselves to contain hundreds of shades running all directions, pulling the eye here and there, never letting it rest. The yellows of his 1965 painting Moving Sunlight quickly fracture into reds, olives, and whites, while retaining the overall impression of a whirling solar surface. Of these color windows, the painter Paul Jenkins, a friend of Delaney’s, said, “These paintings could be for churches of no denomination… All those fierce colors he once knew and painted with, he crushed into a light prism.”

Delaney’s 1968 Portrait of Ella Fitzgerald also deserves attention—Delaney introduced Baldwin to jazz and even wrote song titles and lyrics. Delaney had never seen Fitzgerald when he painted it, but he projected a vision of her in a manner evocative rather than anatomical. Her concrete features are almost entirely obscured; the suggestion of a face floats within a mustard and peach sea. His portraits of Charlie Parker also use vibrant bands of color to effect synesthetic portrayals of sound through light.

These subtle, painterly works demand breathing room to take in, which the Knoxville Museum of Art delivers. Capacious and well-lit, the exhibition space allows for a leisurely perusal of Delaney’s work, though its proximity to the museum’s entrance area can make for a noisy viewing experience. Even if not for his remarkable affiliation with a world-historical figure like Baldwin, Delaney cuts a compelling figure of the Harlem renaissance and abstract expressionist movements in his own right, poised at the intersection of defining American and transnational identities and shifts. The lens of Baldwin’s magnetic presence only serves to amplify his prodigious accomplishment.

Beauford Delaney and James Baldwin: Through the Unusual Door continues at the Knoxville Museum of Art (1050 World’s Fair Park Drive, Knoxville) through May 10.