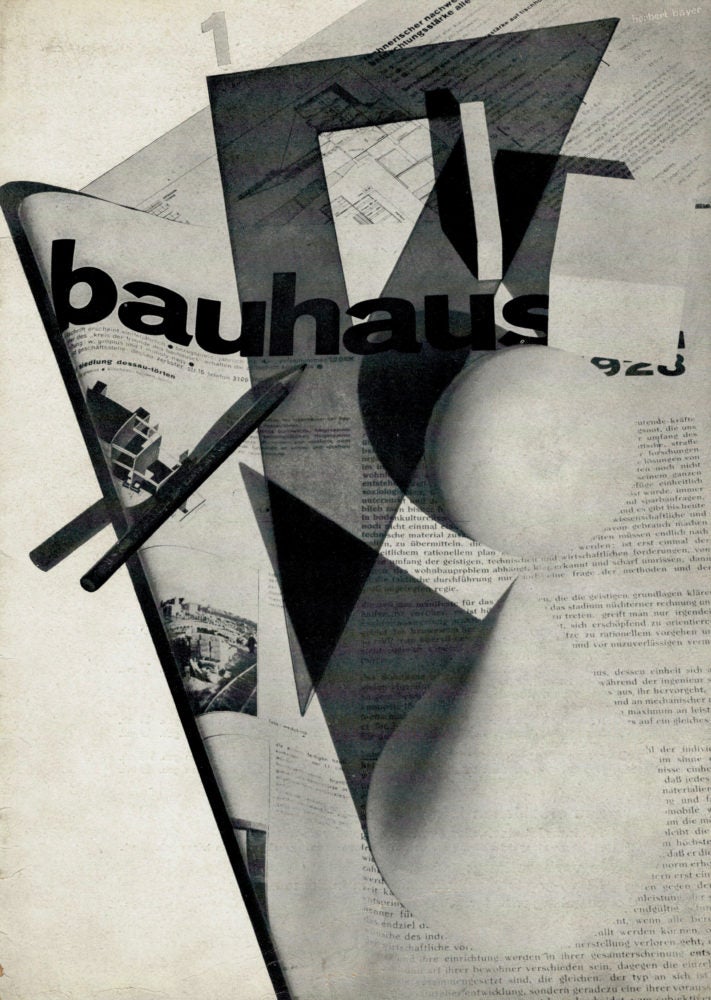

This year, on the occasion of the centennial of its founding, much international attention has been devoted to the Bauhaus, the fabled interwar school of art and design. From Tel Aviv’s Bauhaus Center and São Paulo’s SESC Pompéia to Rotterdam’s Museum Boijmans Van Beuningen and several centers across Germany, institutions around the world have staged major Bauhaus-themed exhibitions. New museums devoted to the school opened this year in the Bauhaus’s first two locations in Germany—Weimar (1919–25) and Dessau (1926–32). The Bauhaus had a brief, final incarnation in Berlin before the Nazis pressured it to close down in 1933.

The United States, too, has witnessed Bauhaus mania this year, from Bauhaus Beginnings at the Getty Research Institute to An Ideal Unity: The Bauhaus & Beyond at the New Orleans Museum of Art. Asheville’s Black Mountain College Museum + Arts Center joined the fray with Bauhaus 100, an intimate, thoughtfully conceived exhibition drawn largely from a recent gift of Bauhaus-related photographs and materials from longtime Cooper Union architecture professor Regi Weile, a student and protégée of Sibyl Moholy-Nagy. (A related show, Bauhaus to Black Mountain: Josef and Anni Albers, is ongoing at the North Carolina Museum of Art.)

Bauhaus and Appalachia are two words whose meanings overlap primarily, if not exclusively, in the cultural petri dish that was Black Mountain College. In operation from 1933 to 1957, Black Mountain brought some of the most inventive minds of the century—including many European intellectuals fleeing World War II—to the mountains of Western North Carolina. The opening of the college dovetailed neatly with the closing of the Bauhaus, and nearly a dozen faculty members or students from the Bauhaus would play prominent roles at Black Mountain College, including the German institution’s founding director, Walter Gropius, and the eminent head of Black Mountain’s arts program, Josef Albers. (Some of these crossover figures, and many others at Black Mountain, also had pedagogical connections to the Institute of Design in Chicago, founded by László Moholy-Nagy in 1937 as the “New Bauhaus.”)

In terms of both ideals and politics, the Bauhaus and Black Mountain College had much in common. Both were founded on progressive, modernist principles, inflected by and embodying propositions for educational reform from such influential forces as John Dewey and the Deutscher Werkbund. Black Mountain was a liberal arts college with an emphasis on the arts, while the Bauhaus’s focus was solely on arts and design, but both schools propounded the revolutionary notion that education, experience, art, design, manual labor, and daily life were not mutually exclusive things, and that they could be most successfully synthesized in an egalitarian, communal, collaborative—even socialistic—setting.

The fact that the two schools developed in times of political and sociological upheaval certainly impacted their radical trajectories. These were periods of seismic civilizational transition caused by two World Wars, the Great Depression, McCarthyism, and more. In his 1935 treatise The New Architecture and the Bauhaus, Gropius considered the fraught cultural atmosphere in Europe after World War I and concluded: “Every thinking man felt the necessity for an intellectual change of front.” [1] Black Mountain College inherited much of this eagerness for change with the influx of the Europeans who began arriving at its doorstep immediately upon its opening. On this side of the Atlantic, that ardent mindset was compounded by concurrent American cultural influences (such as Dewey), and, it might be argued, also by the invigorating fantasy of the pioneering American spirit.

Based as it was in rural Southern Appalachia, Black Mountain College was inevitably subject to criticisms from its neighbors that echoed some of the vitriol directed toward the Bauhäuslers in Germany. The students and teachers at both schools were seen by some as dogmatic freaks: leftist, barefoot, manifesto-writing bohemians bent on changing the world as everyone else knew it. As former student Jonathan Williams—the poet and publisher from nearby Highlands, North Carolina, whose Walks to the Paradise Garden was recently published posthumously by Institute 193—later reflected, Black Mountain was understood by many regionally as a place of “free love, communism, and nigger-lovers—the usual.” [2] (The school enrolled African Americans as early as 1944.)

Its rural setting, however, also set Black Mountain College apart from the Bauhaus, whose three sites were located in metropolitan centers. Black Mountain was removed from urban hubs of culture, in the United States and the larger world—although this did not exempt it from the attentions of intellectual movers and shakers, who continued to visit and teach at the school throughout its twenty-four years of existence. Neither did the school’s rural setting allow it to escape the notice of the FBI, which paid multiple visits to the campus and kept dossiers on a number of Black Mountain figures, including architect and polymath Buckminster Fuller and poet Charles Olson, who served as the school’s rector from 1951 until its closure in 1957. Painter Dorothea Rockburne recalls that, during her time at the college in the 1950s, “FBI people showed up all the time, and they looked like something out of a grade B movie. They always had trench coats on, and you could spot them a mile away.” [3] Black Mountain College was, in the words of one 1956 FBI report, “a very unusual type of school.” One suspects that, to an FBI agent at the height of the McCarthy era, this could only mean something decidedly sinister. [4]

Physically isolated, this “very unusual type of school” offered a beautiful haven for war refugees from Europe, for American pedagogues looking to escape traditional university structures and the craze of city life, and, of course, for students who landed at the school from all over the United States (and some from abroad), most of them seeking an alternative approach to learning. Mistrusted by its neighbors and by the FBI, enclosed by a ring of Blue Ridge Mountains, and content with the sort of freedom this isolation afforded, the school became a kind of hermetically sealed hothouse of concentrated idea-making.

What did it mean to be an avant-garde artist in such a place and time? Or perhaps the question is better phrased: how could one not become an avant-garde artist in such a place and time? The stars in the Southern Appalachian skies aligned, and Black Mountain College hosted, hired, nurtured, taught, inspired, or infuriated into action some of the twentieth century’s most relevant artistic figures, including Josef and Anni Albers, Robert Rauschenberg, Jacob Lawrence, Merce Cunningham, John Cage, Cy Twombly, Ruth Asawa, Willem and Elaine de Kooning, and a litany of others far too long to list.

Today, of course, the notions of “hub” and “periphery” have all but lost their meanings. We are all connected, as the saying goes—and an artist based in rural Appalachia has (virtually, it must be noted) as much access to information, influences, influencers, materials, and experience as any denizen of Paris, Tokyo, or Bushwick. Networks and audiences—the human kind—may be more difficult to establish from this “remote” position, but every day seems to introduce new ways of transmitting, of being salient, to an ever broader circle of potential interest. There may be no such thing as isolation anymore.

These times, it goes without saying, have their own bitter political and cultural flavors: racism, nationalism, misogyny, homophobia, and xenophobia are part of our daily dialogue with national leaders and with one another. And as much as the internet has offered the wondrous benefits of global connectivity, it has also enabled conspiracy theorists—along with the rest of us—to live in a world of mistrust. In the South, we contend with our particular brand of racial and economic inequities, and with festering resentments over a history that refuses to be rewritten, despite the dogged efforts of many. But our great connectivity has also allowed for new Appalachian sub-communities—from Queer Appalachia to the Affrilachian Artist Project—to coalesce and raise their voices against all the slings and arrows such communities face across the region. It has also offered the very oldest Appalachian creative communities—including mountain craftspeople and artists of the Eastern Band of Cherokee tribe—new reach, new opportunities for collaboration, and new markets.

The mountains of Appalachia are marginal, peripheral, backward, but they are also filled with inspiration and brilliance—and connected, both within and without.

So what does it mean to be an artist today, in this Appalachia? As the Bauhäuslers and the Black Mountaineers knew well, artists are equipped to serve as the agents of a changing ethos. They are unabashedly capable of robbing the past to feed the future. Some in Appalachia choose to look to the attributes and traditions of this place—the landscape, the lore, the history of craft, the Civil War, even the legacy of Black Mountain College itself—and synthesize whatever they find useful into fresh work with fresh meanings. To name only a few who are inspired by this Appalachian context in one way or another: sculptor Molly Sawyer, painter Julyan Davis, photographers Mike Smith (whom I profiled for this magazine last December) and Rob Amberg.

Although based in Appalachia, many (if not most) other artists, of course, engage with matters not directly related to the region, confronting through their work any number of larger societal, political, environmental, relational, or simply aesthetic issues—and finding they can operate with some degree of success from this outpost. Among these are photographer Clarissa Sligh, painter Margaret Curtis, the concept-driven Workingman Collective, and the multivalent Mel Chin, who received a MacArthur “genius” grant just this week.

Notions of community and common values were central factors in the creative foment of both the Bauhaus and Black Mountain College. Today, our communities convene in the disembodied neighborhoods of Cyberbia. But there is no question that place—real place, physical place, peopled with friends as well as strangers—provides valuable surprises of creative combustion that are unlikely to happen online.

On November 14, the Asheville Art Museum will reopen after a three-year, twenty-four-million-dollar renovation with a survey of work by fifty regional artists, exuberantly titled Appalachia Now! We may hope that this latest investigation, organized by New York–based curator Jason Andrew, will shed new light on whatever it is that makes this region cohere, if it does: shared ideals, shared legacies, shared societal transitions, shared outrage. Or none of the above.

Bauhaus 100 was presented at the Black Mountain College Museum + Arts Center, Asheville, North Carolina, from June 7 through August 31, 2019. Bauhaus to Black Mountain: Josef and Anni Albers, curated by Julie Levin Caro, is ongoing at the North Carolina Museum of Art in Raleigh until January 12, 2020. An Ideal Unity: The Bauhaus & Beyond at the New Orleans Museum of Art through March 15, 2020. Appalachia Now!, curated by Jason Andrew, opens on November 14 as the inaugural exhibition of the renovated Asheville Art Museum .

[1] Walter Gropius, The New Architecture and the Bauhaus (1935), trans. P. Morton Shand (Cambridge, MA: MIT Press, 1965), p. 48.

[2] Jonathan Williams, in Richard Dana, Against the Grain: Interviews with Maverick American Publishers, (Iowa City: University of Iowa Press, 1986, repr. 2009), p. 201.

[3] Dorothea Rockburne, interviewed by Connie Bostic, Black Mountain Studies Journal 1 (2002).

[4] John Elliston, “FBI Investigation of Black Mountain College Revealed in Newly Released File,” Carolina Public Press (August 5, 2015).