One and a half centuries ago this year, Atlanta burned to the ground. Such occasions beget a common but important question about Atlanta architecture: Why does Atlanta destroy its history? Some wonder whether Atlanta has any history at all, and if so, where is it?

While potential answers indicate a complex set of issues, one can distill several key factors to explore this apparent absence: Atlanta’s youth as a city in global terms; its history of segregation, white flight to the suburbs, and gentrification; political cycles of support and disinvestment; and an inability of preservationist infrastructure to protect endangered structures. Economics encompasses the likeliest factor, however, and the fuel for that engine derives from its history and identity as tied to a man named William Tecumseh Sherman. In this Union general’s influential wake, Atlanta flaunts itself as a place of creative destruction, wherein only through destroying the past can the city progress into the future. Sherman reforged Atlanta as a capitalist testing ground, where property owners and developers equate the details of the existing urban fabric with property values. Atlanta reduces architecture to a mere machine for maximizing profit, to objects that are short-term, replaceable, and trendy. It considers any such object as interchangeable as the next, and every parcel is scrutinized for optimized return on investment.

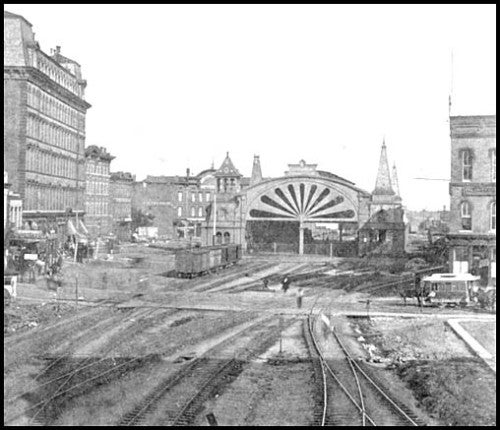

For Atlanta, a city with such a troubled racial and developmental history, the economic need of preparation for the future has always eclipsed the preservation of the past. Atlanta’s embracing the logic of creative destruction means the city has only five structures that date from before 1870, all of them now in various states of rehabilitation or ruin. The condition prevalent in Atlanta, as in several other cities, has resulted in the sites of many historic photographs being unidentifiable today. Google Earth and Street View now function as testaments to the living past, a Schrödinger’s cat situation for architecture and urban form. Otherwise, destroyed buildings might be re-presented later in other developments, such as the 1871 Union Station at the Mall of Georgia, or reconstructed on site, such as I.M. Pei’s Gulf Oil Building. Much of the built legacy of the Centennial Olympic Games, just 18 years ago, has been eradicated or will be in the immediate future. Governmental regulations have even encoded the tactics of creative destruction, equipping municipal organizations and developers with the ability to destroy any property dangerous to human occupation.

The idea of creative destruction is older than Atlanta by more than a millennium. With early sources as varied as Hindu and Christian texts, as well as Ovid’s discussion of the phoenix in Metamorphoses, the idea traversed from the mythological to the philosophical by way of Goethe and Hegel. Marx and Engels then adapted it into their economic theory as early as 1848 in The Communist Manifesto. They argued that bourgeois society had created a capitalist machine that functioned more efficiently by destroying old markets in order to create new ones, and that this cyclical system generated recurring economic crises as a byproduct.

Nietzsche expanded on this idea in Thus Spake Zarathustra (1883-85), stressing that an ideal future society would need creators who were unafraid of constructing a world amid the ashes of the former one. In Nietzsche’s concept of the Übermensch, the creator and the destructor are synonymous: “How could you wish to become new unless you had first become ashes!” German economic theorist Joseph Schumpeter principally popularized the idea of creative destruction as “the essential fact about capitalism.” Schumpeter coalesced the pre-WWII concepts of German economics developed primarily by his mentor Werner Sombart, who wrote that “from destruction a new spirit of creation arises.” This term became a buzzword to describe the technological revolution at the turn of the 21st century, but its popularity followed its own pattern of rise and ruin in the dot-com boom and bust. . . .

Read the full article in BURNAWAY #2: EXCHANGE!

Click here to order.