I first saw works by Atlanta-based artist Y. Malik Jalal in a two-person show early last year at Dianna Settles’s storefront gallery Hi-Lo Press. Jalal’s paintings in that show—including a pink, square canvas bearing appropriated images of SpongeBob SquarePants and Winnie-the-Pooh alongside text spelling out OBAMA CARE and a crude drawing of the Atlanta Falcons logo—possessed a self-assured sense of control that made me wonder why I wasn’t already aware of this artist. His works conveyed a sharp eye for composition and suggested the influence of collage and assemblage techniques, as well as common urban sights including flyposting and commercial graphic design.

Last fall, at the Gallery by Wish in Atlanta’s Little Five Points neighborhood, Jalal contributed two paintings and a sculptural installation resembling the stickered door of a gas station to a brief exhibition celebrating the twenty-fifth anniversary of the release of Wu-Tang Clan’s debut album Enter the Wu-Tang (36 Chambers) in 1993. (Jalal wouldn’t be born until the following year.) Though it wasn’t a painting, the door sculpture was easily recognizable as Jalal’s handiwork, materially invoking Atlanta’s Dirty South landscape of concrete and wire, glass and steel, neon and red clay.

I visited Jalal’s studio in his home in Atlanta earlier this month. We began discussing one of his new works, Thunder is a Woman with Braided Hair—a painting-sized, quilt-like form combining various textiles and found objects—which led to an exchange about craft, labor, and Jalal’s occupation as a welder. Our conversation was conducted in person in February 2019 and has been edited for publication.

Logan Lockner: In some ways, the sensibility of a quilt seems like it’s always been present in your work—kind of like a collage or patchwork idea—so for you to literally play with quilting techniques makes sense, especially considering the place that the quilt occupies in Southern art history and African American art history.

Y. Malik Jalal: Yeah, especially with Gee’s Bend… I love that work. I’m really interested in craft.

LL: That make sense with what you’re saying about being a welder.

YMJ: Exactly. I have had a pretty privileged existence, but I definitely romanticize the notion that I’m part of the working class, you know. Eventually, the goal is be in the studio all the time, but I kind of wrestle with that. I want to maintain some craft—or at least a relationship with it, even if I’m not directly a craftsman or whatever. My father and a lot of the men in my family—and the women, for that matter—were working-class people and had pride in their craft.

Mysticism and religion are definitely very important parts of my work too. It’s been ever-present in my life, as far as my family is concerned. My father converted to Islam when he was sixteen and changed his name, and my mother comes from a Southern, Pentecostal church. They both abandoned that to some degree, but it’s kind of had this lingering effect.

LL: How does that express itself in your work?

YMJ: Well, I certainly like to think that I’m tapping into something that’s outside of me. And I just find that, culturally, religion and specifically Christianity have had a bigger impact on me because of my mother. I think it’s something maternal.

LL: So your mother didn’t convert?

YMJ: No, she did not. My dad changed his name, so we have Muslim names, but it’s like these little fragments. Like we would say an Islamic prayer before we would eat, and my mom kind of played along.

LL: Being able to balance those things seems… not obvious, especially in the suburban South.

YMJ: Yeah, my dad is from Brooklyn. He was in the military and is a very smart man. But yeah, my mother—you know, as moms do—has definitely been more of an influence on me.

In a lot of ways, I feel like I don’t have a connection to my history, I guess. I lost all of my grandparents when I was really young, and there was a lot of trauma associated with that. Now that I’m of age, I wish I had more of a connection to that. A lot of times, I feel like these works are fictional in some way but personal at the same time.

LL: Something I noticed when I first saw your work was your ability to juxtapose sort of lowbrow, juvenile pop culture references with visual references to specific historical and political moments, like the 2004 presidential election or debates over Obamacare. It feels funny and smart and subtle.

YMJ: Yeah, I’m specifically interested in the history of the Civil Rights Movement and the history of the United States after the Civil War more generally. Although I don’t really intend to make any particular statements about things, I like to add them to the work, whatever I’m personally processing. I collect a lot of things and consume them, and pop culture and American political history are probably the two things I consume the most.

LL: Materially?

YMJ: Yeah, in a very real sense. I like to kind of destroy things, either in the studio or through daily use. Like that used to be a t-shirt that I used to wear—that Darth Maul t-shirt—and I left it in my truck for a while, and it became this interesting, decayed image. I just like to let things collect dust, you know, kick them around for a while.

LL: What’s the guiding principle for these compositions? How do you decide what elements belong to each piece after all that collecting?

YMJ: It’s very intuitive. This one [Thunder is a Woman] took me a while. When I paint, there are probably like four or five paintings under the final painting, and typically it’s just me kind of pasting things and seeing how I like it. Oftentimes, I feel as though I could do better, and so I just paint over it, or rip it off, or something like that, but with this I didn’t really have that freedom. I had to be confident—I had to commit to something before I sewed it, so this was a little bit of a different exercise.

Whatever elements I initially put on a paining are probably going to get covered up, and I sort of submit to that. There are a lot of decent paintings underneath the ones that I’ve shown. And sometimes I try to hold onto stuff, like those oranges.

LL: Yeah, I was going to ask about those. They seem to be a recurring image.

YMJ: I think that’s because they’re easy, to be honest. Fruit and flowers are these gems of the natural world, and they kind of fill in blanks in my work, oftentimes becoming the subject or falling into the background. It kind of takes less thought. You don’t need to know a lot of context or understand connotations that a lot of people out there don’t see.

LL: They sort of just get to be the Platonic ideal of an orange.

YMJ: Yeah.

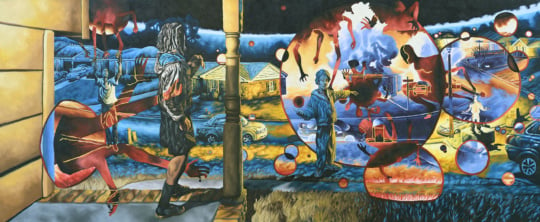

Jalal and I left the garage area where we had been standing and moved into the living room, where a wide, large-scale painting dominated an entire wall. In the painting, an image of the face of a man wearing a kofia, a traditional East African cap, appeared to float over blocks of color reminiscent of a Stanley Whitney painting.

YMJ: I’ve been working on this one forever, and I keep painting over stuff. I started that portrait in August and haven’t touched it since, but I’ve added a number of other elements. I wanted to do a painting shaped like a billboard, but this one’s actually kind of wearing on me. I want it to be done already.

LL: How do you choose or find the portrait subjects?

YMJ: I guess that’s a place where my father’s influence comes in. This is a portrait of Elijah Muhammad. I’m fascinated with the relationship between the Black Power movement and Islam, and between the Civil Rights movement and Islam.

Elijah Muhammed is kind of like a Jesus-like figure. I feel as though prophets only really exist in oppressed communities. There’s a notion of heroism associated with that. But he’s also contradictory: he espoused marital fidelity but wasn’t faithful himself, and he was even associated with straight-up assassinations. So understanding prophets as heroic is paradoxical. I relate to that in some ways.

LL: Well, we associate a certain heroism with being an artist in a similar way, especially a painter.

YMJ: Yeah, exactly. My own insecurities are kind of wrapped up in it too. Sometimes I feel kind of fragile, like I’m a fraud, you know.

LL: It may be part of what you’re talking about in terms of an association with the working class, but imagery related to cars and automotive branding also frequently appears in your paintings. There’s a Chevrolet logo in this painting with the portrait of Elijah Muhammed.

YMJ: Definitely. I love trucks. I love big trucks. When I was a kid, I used to watch this one particular VHS of big dump trucks, and that’s kind of stuck with me. My father owns a landscaping company, and when I was fourteen I started working for him, and that’s something we share: fix it yourself, drive old trucks, get dirty, shit like that.

But soccer was my original passion. Of all the things I’m good at, I’m the best at soccer.

LL: Better than painting?

YMJ: Yeah, without a doubt.

LL: That reminds me of something the painter Ridley Howard said in an interview about his friends either being sports fans or painters. He talked about admiring the sort of “irrational romanticism” that it takes for you to become emotionally invested in a fictional space that ultimately doesn’t mean anything, whether a sports game or a painting.

YMJ: What I learned on the soccer field definitely plays a role in the way I work in the studio. When I’m here, it feels very much like a dance or something, like a physical activity. I listen to a lot of hip-hop, and I get kind of worked up. I’m competitive and want to push myself to be better.

Soccer is a creative sport, too. Football is a sport with a lot of rules, and each player has a very specific role, and they do that role their entire career. They tackle people, they hit people, or they run the ball. But soccer doesn’t have those distinctions. It’s very intuitive and organic. I feel as though that comes through in my work.

LL: Cartoons seem to be another recurring source of your imagery.

YMJ: Yeah, and I guess for a similar reason. When I was a kid, I felt like I was deprived of cartoons. My father didn’t let us watch TV, and if we did, it was a very special occasion. But as soon as I got out of school and out of my parents’ house, I really fell in love with cartoons. I like the immediacy of it. A cartoon communicates very concisely. I can spend a week on a portrait, then not like it and paint over it, whereas cartoons are easy. A lot of these things I use can be used as armatures for something else, for an abstract painting, or as part of a background.

Pop culture, television, advertising: that’s what’s in my visual landscape. That’s what I see. Painting cartoons makes as much sense as painting anything else nowadays. I don’t see beautiful mountain streams—I see advertisements and garbage. But there’s as much beauty in that, and you can make it your own.

This article features one of the artists participating in Art Crush, Burnaway’s upcoming auction and fundraiser, on Saturday, February 16 at The Factory Atlanta in Chamblee. Find out more about this year’s event—which includes a silent auction, interactive installations, live printmaking, and more— and purchase your tickets here.