In 1870 more than 22,000 formerly enslaved Black people and their descendants listed their surname as “Washington” on the first United States census conducted post-emancipation. Seventy-seven of them lived in Oktibbeha County, Mississippi; one of them was named Saul. Saul begat Saul who begat Louis who begat Louis, and then there was me.

I spent the first nine years of my life in St. Louis before my parents and I moved to Huntsville, Alabama. The state seemed like a mystical, terrifying, backwards place. When we moved in 1997, Alabama was still three years away from overturning its ban on interracial marriage. In St. Louis I’d learned cursory lessons about slavery and civil rights in my predominantly Black elementary school from mostly Black teachers. But once I moved to Huntsville, my new, white instructors complicated the narrative with teachings about states’ rights and benevolent slave owners. Everyone seemed to have a fraught relationship with the state’s prominent role in Black American history.

Alabama loves to brag about its role in the civil rights movement, but struggles to be honest about why the movement was necessary. Even today, the seal of the state capital, Montgomery, features at its center a star adorned with the words “Cradle of the Confederacy,” while its outer circle reads “Birthplace of Civil Rights”. Two concepts that are constantly seething at each other, and never quite reaching reconciliation. And that is what the Equal Justice Initiative (EJI) aims to do.

Since 2018 EJI has launched three legacy sites in Montgomery to teach the world more about the path from slavery to mass incarceration; it is a noble and necessary undertaking. EJI does so first through the Legacy Museum, a viscerally informative experience about the history of slavery, Jim Crow laws, and mass incarceration in the United States. Then, the National Memorial for Peace and Justice, an awe-inspiring and innovative monument to America’s lynching victims. Finally, this year, the organization debuted the Freedom Monument Sculpture Park, a seventeen-acre park that sits alongside the Alabama River. The park’s stated goal is to honor the lives of the more than ten million Black people who were enslaved in America. Through its initiatives, EJI also fills a role in public history, doing work at the county and local level to help communities acknowledge their history of racial violence.

I visited the Freedom Monument Sculpture Park twice: just a week after it opened in April 2024 and again in June. The park pays tribute to those impacted by enslavement through the work of over two dozen artists whose sculptures are placed throughout the park, alongside artfully designed, immersive educational pieces. Many of the incredible works were created by some of the world’s most prominent living artists.

Upon entering the park, visitors are greeted by Simone Leigh’s imposing Brick House (2019), a sixteen-foot bronze of a Black woman’s afroed head and torso. There is also Thaddeus Mosley’s Benin Strut (2020), a light brown, bronze, abstract sculpture that features a central figure with broadly swinging arms; the title and the work’s pose imply swagger and pride. Towards one end of the park, 108 Death Masks (2018) by Nikesha Breeze offers a somber reflection of the human faces of slavery. Breeze’s life-size masks are arrayed single file on a simple stone wall, at about eye level. At four-feet-eleven-inches, I had to look upward a few inches to make eye contact with them, an experience that only added to the humanlike interaction between viewer and art. I caught myself looking for familiar features—my grandmother’s cheekbones, my grandfather’s forehead, my lips—in the lifelike faces staring back at me.

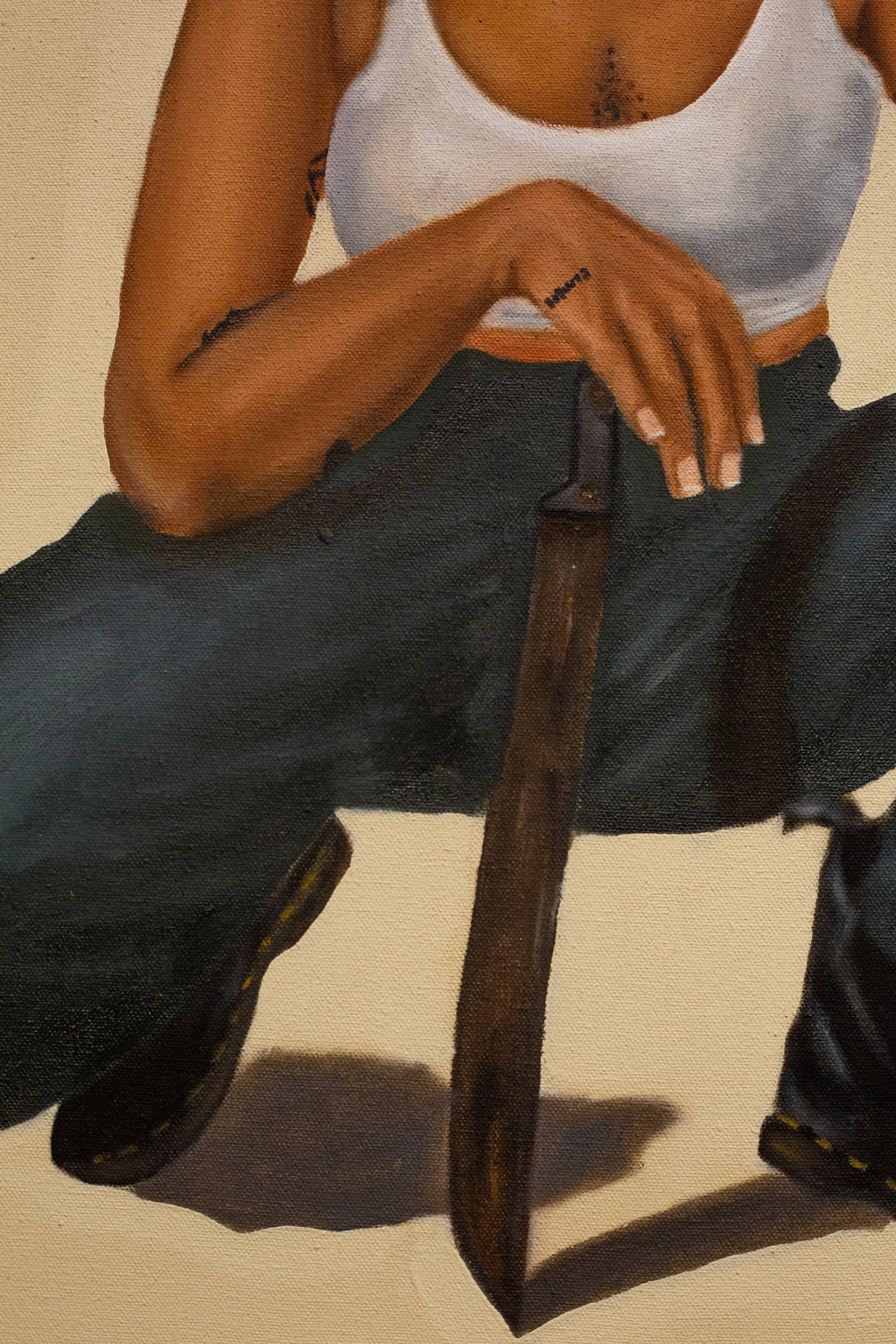

The park serves as a repository for brilliant art by and about Black Americans, but falls short in some ways in its curation. Rayvenn D’Clark’s Black Renaissance (2023) sets the tone for many of the pieces in the park. Imposing and regal, the work’s set of five nine-feet-tall dimpled bronze heads were created from three-dimensional scans of live Black models. They take up substantial space, forcing the viewer to imagine what a commensurate body would look like, and making the human faces of the enslaved people represented unavoidable. D’Clark’s work is probably the most dynamic of the pieces that fall into a trope I began to call “sad bronze Black people.” Sometimes it’s sad bronze Black people picking cotton. Or sad bronze Black people holding each other. The sculpture park is meant to be EJI’s attempt to use art to counter the preexisting and limited narratives about the history of slavery. But however incredibly well crafted, the figurative sculptures do not add anything to the story the park is trying to tell.

Some of the works do deliver. Alison Saar’s Tree Souls (1994) comprised of chiseled human figures in wood, shown emerging from a dense web of roots on the ground and ascending up towards the sky. Saar’s figures are wisely placed in between historical sections about resistance and rebellion, where they evoke images of alien abductees or souls rising to heaven, either a better alternative to bondage. The wood, as opposed to the bronze of many of the sculptures in the park, gives the work a folksy, organic feel. They appear as if they really did grow from the Montgomery soil, and are rising twenty feet high. Tree Souls’s elevation and natural materials contrast with the park’s other works, which feel weighted and solemn. Likewise, the three towers of miniature tambourines that form Allison Janae Hamilton’s Love Is Like The Sea (2024) is one of the only sculptures that feels like a monument to joy. Though silent, the tambourines call to mind music, specifically their use in Black gospel music. The artist’s choice to paint the bronze white also distinguishes it from the rest of the dark and moody bronze sculptures. Like Saar’s work, Hamilton’s stacks, the tallest at twelve feet high, evoke a stairway to heaven.

EJI’s other sites offer comprehensive history lessons and important counternarratives, and the sculpture park is no different. The educational elements of the park, which take visitors through the history of slavery, are insightful and the history they depict is intentionally told. One such example is a set of wooden markers that list the number of people that were imported as human chattel into specific ports. One reads: Tybee Island, GA 1803 – 462. The markers provide an empirical counterbalance to the art in the form of geography and numbers. Arranged in a row of various sizes, the markers lead to signage that reveals the full number of African people shipped across the ocean to the United States. The park relocated several original nineteenth-century cabins where enslaved people and their descendants lived well after emancipation. The cabins are marked by simple podiums with text explaining their significance. Especially in the hot June humidity, it is difficult to imagine these small structures being a respite for entire families.

Alabama loves to brag about its role in the civil rights movement, but struggles to be honest about why the movement was necessary.

However, while the park’s historical entries are rich, detailed, and thoughtfully composed, there is not much context for the art itself. Each is accompanied by just a simple placard showing the artist’s name and the work’s title, date, and medium. Considering the sculptures come from artists from across the globe and employ a range of mediums to honor the memories of enslaved people, I wish the park provided the viewer with more background about the art and artists. That the park does not allow photography—as is the case at the EJI’s museum and monument—also forces the viewer to encounter the art in the moment, observing and interpreting the works by themselves. However, I left wanting more. I was looking for details about the artists, insight into their processes, artist’s statements, etc. Most arts institutions offer some interpretation of artworks in order to connect them to a larger theme or mission or to educate the viewer. I relish such opportunities to learn about unfamiliar artists and techniques as well as to expand upon history that is new to me. Especially in a place like the sculpture park, which is devoted to recontextualizing the history of slavery through art, I wanted to know all I could about the art itself. Why did Hamilton choose to paint her tambourines white? Where did the cotton in Kwame Akoto-Bamfo’s Mama I Hurt My Hand (2023) come from? Which pieces were commissioned for the park and which were acquired through other avenues? Because the park so thoughtfully delivers its history lessons, it was glaring that they omitted so much information about the art itself.

The park successfully achieves its goal of teaching visitors about the horrors of slavery. But what lingered with me most was not the brutality of it, but its mundanity: the way it wove itself through every facet of American life and culture, the bureaucracy involved in trafficking human beings, its lingering environmental and economic impacts. The commonly understood history of the supporters and practitioners of slavery as ignorant, ravenous monsters does not fully capture the insidiousness of the practice. They were brutal, but they were also good at paperwork.

A simple gray, stone marker, engraved with black text tells the story of Amy and Caty Butcher, a free mother and daughter who were kidnapped and taken from the North and enslaved in Huntsville, the city I have called home for most of the last twenty-six years. Theirs is not a journey of starlit navigation out of bondage, but of a court case that dragged on for six years at the end of which they were ultimately legally and procedurally denied their freedom. These women, born into freedom, had hired a lawyer to represent them, and the law and reason of the time could not see their humanity. Their struggles and those of others are depicted throughout the park.

A lot can change in two months. When I first visited the sculpture park in April, the high that day was seventy degrees and I wore a light jacket around the park, wrapping it close to me as a breeze from the river swept by. By June it was nearly ninety degrees in the afternoon, and I used a notebook to fan myself. In April I was in Montgomery, a mere two miles from the park in the Alabama State House, to advocate during one of the state’s most brutal legislative sessions. By June, Alabamians had seen the temporary loss of access to in vitro fertilization, the weakening of labor laws, and bans of diversity, equity, and inclusion programs at public colleges. Alabamians watched lawmakers hem and haw over whether to feed 500,000 of Alabama’s poorest children—a disproportionate amount of which are Black and Brown, a living remnant of slavery. In April, Kehinde Wiley was one of the most revered Black artists in the United States, and his piece An Archeology of Silence (2021) was one of the park’s most notable acquisitions. By June, he had been accused of sexual assault several times over.

The first time I visited the park in April, I exited aggrieved. I felt like I had seen just another monument about sad Black people, another story of Black defeat. Like this is all our, Black people’s, history is and will ever be. I felt like I had left a space that was intended for white tourists wanting to “do better.” But what about me? What about us? What is there to inspire Black people living with the scars of slavery today? What are we supposed to take away from another reminder that our ancestors’ lives were dictated by suffering at the hands of a merciless economy? And what hope do we have that our children’s won’t be dictated by the same?

I wonder what would have satisfied me. A monument, an entire park, an entire museum dedicated to brutal slave rebellions? Maybe.

By June, as the world heated up, I cooled off. EJI is doing incredibly important work. Work that if taught in Alabama’s schools might be illegal. But it’s also work that deserves a compassionately critical eye. The art shown, the narratives created, the histories told are intentional. And even the best of intentions deserve scrutiny.

As I was leaving the park the second time, I stopped by the newly minted National Monument to Freedom, the park’s pièce de résistance: a wall 50 feet high by 150 feet wide etched with the 122,000 surnames of recently emancipated slaves and their descendants, collected from the 1870 census. Black American visitors are encouraged to search for their surnames and those of their ancestors on the massive wall. A young, handsome Black attendant with a nice smile offered to assist me in looking up my family name. When I told him “Washington,” he said, “Oh, I don’t even need this. I know exactly where you are.” He took me to a panel about six feet off the ground and explained that these were some of the most common names they are asked to find. He sees Washington every day. And there, amongst Walker and Moore, Robin and Anderson, I saw myself too.

This essay is a feature release of Burnaway’s 2024 theme series Knock Knock.