Dallas has two bridges named Margaret. Both were named for heiress/philanthropists, and both are credited to starchitect Santiago Calatrava. The Margaret McDermott Bridge and the Margaret Hunt Hill Bridge cross the Trinity River and connect downtown with the city’s rapidly developing west side. “The Margarets” also form a frame around the proposed Harold Simmons Park. This urban park, at nearly 200 acres, would be named for the late billionaire Harold Simmons. I read up on the guy. Not a fan.1 So, for the rest of this article, I will be referring to the-project-between-the-Margarets by a local nickname, Margaritaville.

Margaritaville is both a place and a collective delusion. It exists simultaneously as a marshy floodway structure and as a proposed urban project that puts even the High Line to shame. For almost twenty-five years the city of Dallas has been teasing a version of the Margaritaville park. Despite a much-publicized suite of 2018 architectural renderings and promises to break ground soon, the site remains bare, spare, and sort of ugly. Margaritaville’s blankness makes it a perfect screen for the projection of fantasy.

The development of urban parks has a significant impact on real estate, as parks increase the value of nearby properties and attract new development. The lingering promise of Margaritaville has fanned the fires of speculative real estate ventures all along the riverbanks. The kinetics of excited capital have generated seemingly endless suites of development plans, architectural renderings, and pitch decks. This glut of images has ultimately created a fog in the imaginary, leaving Greater Margaritaville as one giant maybe. All of these maybes seem to be discordant with the actual reality of the river.

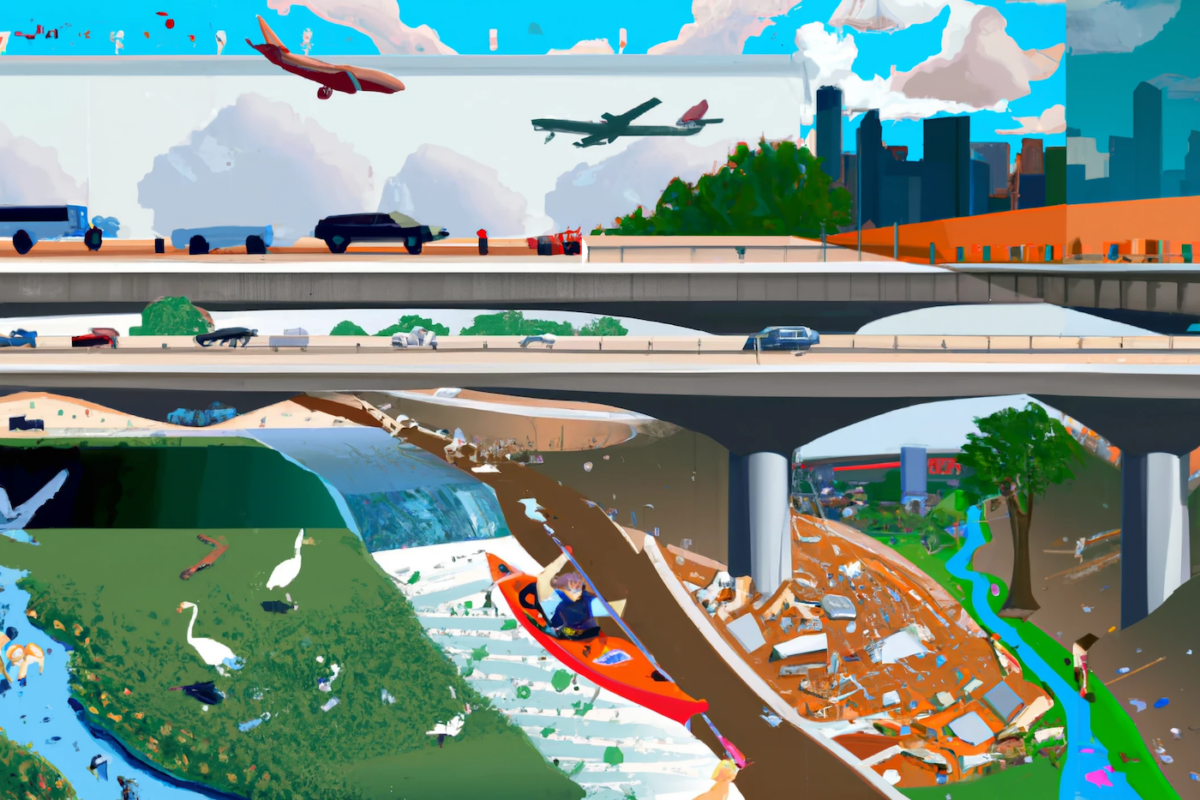

Margaritaville, besides being a future mega park, also happens to be part of the Dallas Floodway. As the name implies, Dallas has a history grappling with the river and its flooding. T-Bone Walker laments in his 1929 song “Trinity River Blues”: That dirty Trinity River, sure have done me wrong / It came in my windows and doors, now all my things are gone. After devastating flooding in the early 1900s the city developed a plan to divert the river into a controlled channel by using levees. To achieve this, city planners physically moved the river’s banks, taming its once calligraphic spine into a mechanically straightened gutter. The resulting floodway created a 2000-foot-wide gash with levees that average around thirty feet tall.

In its current form, the Margaritaville park encompasses a few overlooks, some way station signage, and a network of gravel paths that cut through a vast lawn of grass and puddles. Walkers, joggers, and leisurely cyclists can find themselves alone here for long stretches. It’s the kind of place you smoke a joint, or bring your dog to be off-leash, or both. After some acclimatization to the city ambience, it even becomes peaceful. You will find a wide array of migratory birds, and in the spring and early summer there are wildflowers. But that sort of off-the-shelf nature isn’t Dallas enough for park planners. Park planners believe Dallas needs a little landscape architecture to know they’re in a place. To them, Dallas loves Corten steel, decomposed granite, native grasses, and gabion walls. The people want artisanal ice cream, selfie stations, and—of course—shopping.

This is the world that is promised by Michael Van Valkenburgh Associates in their renderings commissioned by park planners. The seductive pitch, which debuted in 2018, features a watery and lush paradise—full of smiling multi-racial children, canoes, and people riding horses under the Margarets. It proposes a multi-level and sprawling promenade full of mature trees, prairie plants, cafes, and playgrounds. Their design essentially retrofits the floodway to achieve the ne plus ultra of urban planning and dissolve the division between city, infrastructure, and nature. One thing that the renderings don’t feature is the trash.

Margaritaville has unbelievable trash. On a recent walk, I surveyed one square meter near the water. I found: a sun-bleached shampoo bottle, an empty bag of La Princesa Chichurritos, craggy styrofoam bits, a Whataburger cup (also styrofoam), a can of Vooz Blue Razz Hydration Sensation Sports Drink, water-bloated dry cat food, and single serving, hazelnut flavored coffee creamers—some opened, some sealed. Rapid surface runoff accumulates this remarkable trash. It’s everywhere: ensnared in trees, floating in puddles, matted down into the grass high on the riverside slope. The more you look, the more you find.

Usually, the Trinity River is a narrow thread of water in the landscape, barely visible between the levees. At times, when the region’s characteristically intense thunderstorms arrive, it produces flash floods. The very nature of the Floodway invites swell, reaching a staggering forty-two feet in 2015. The deluge comes from the far and wide development that is the Dallas Fort-Worth Metroplex. Litter from neighborhoods, parking lots, highways, and gutters finds its way to the river. Margaritaville is a cocktail strainer.

Contrary to the virescent and blue renderings by Michael Van Valkenburgh Associates, the Trinity River is brown. It carries a heavy sediment load of silts, soils, and clay picked up from its banks—but it also carries a lot more. Denis Qualls, senior program manager for Dallas Water Utilities calls The Trinity River “effluent dominated,” meaning there is regularly more treated wastewater added than is actually supplied by the river.2 At least this added water is clean. It probably wouldn’t surprise you to learn a river passing through an urban area contains fertilizer, pesticides, herbicides, and industrial waste. In fact, the state has deemed the Trinity River unsafe for swimming and water skiing because of elevated bacteria levels associated with animal waste and human sewage. There are also so-called legacy pollutants in the sediment such as PCB’s, arsenic, and DDT.

Welcome to Margaritaville.

The modern history of Margaritaville begins in the late 90s (before the Margarets) when the city approved a quarter of a billion dollars bond to transform it into a park. It’s a history as murky as the Trinity. In the wake of this injection of funding, local organizations were created and run by some very influential (read: rich) people who were entrusted with the city’s money and the park’s future vision. Their PR headline: Create the largest urban park in America. Their charge: Transform what was once a liability into something profitable. Aspirational subtext: Turn your weakness into strength.

One chapter of the Margaritaville saga involved a complex scheme to pay for the park system in the floodway by creating a toll road. The plans for this road morphed into a six-lane superhighway called the Trinity Parkway. It took the city over a decade to realize a) they couldn’t afford to build it, and b) that it just might be a bad idea. As cranky local journalist Jim Schutze put it in the Dallas Observer, “the Dallas City Council finally killed the unbuilt project, in part out of a concern that, if the expressway were placed out where it floods, when it flooded, it would flood.”3

Reeling from the failure of the toll road and looking for a win on the river, the city approved a project to create an artificial white water rapid on the usually placid Trinity. Denver comes to Dallas! It was doomed from the beginning. What was sold to the public was a watercolor of an idyllic scene of a kayaker drifting through the set of A River Runs Through It. When completed in 2011, it looked more like a municipal spillway. It was closed to the public shortly after opening because of bad engineering. The bypass channel turned out to be more dangerous than the rapids. This situation triggered the U.S. Army Corp of Engineers, who has ultimate jurisdiction over the river, to intervene. They threatened legal action in 2015 if the structure wasn’t removed, because as it turns out, it’s against federal law to close a navigable river. What began as a $1 million dollar project, ballooned to over $4 million to finish, and required an additional $2 million to remove.

I bring these histories up not to illustrate that the local government and organizational stewards of the Trinity River appear to be perennially incompetent. That has long been established. I bring it up to illustrate the power that a few architectural illustrations and a PR team seem to have on this river. Nested in the renderings, likely composed in Photoshop, is an inherent erasure of reality, and of course histories. Embedded deep in the layers of the .psd files is the fact that this river, once called the Arkikosa by the Caddo people, bears witness to the sins of the city. While it may seem perfunctory into today’s political climate to remind ourselves of genocides, slavery, and displacement—this violence is the metadata of the park and a history inconvenient to boosters.

It requires very little imagination to see that these renderings have exacerbated the gentrification of West Dallas. Long ago, speculative real estate seized the promise of the Michael Van Valkenburgh Associates version of Margaritaville. Condos and apartments, essentially made from the same material as pizza boxes, have begun to spring up on both sides of the levees. Homogenous new constructions (what my wife calls Sketch-Up-vomit) are mixing with older neighborhood homes currently besieged by the national plague of the fixer-upper-flipper. Margaritaville was the tip of the spear leading development into West Dallas and brought with it the Four Horsemen of development: coffee shops, breweries, plant stores, and ax-throwing. Even as I write this article, a massive land deal has taken place, with more than ninety properties and thirty-five acres of land sold to a Nebraska-based investment company which signals further large-scale development. The peripheral growth promised by the park planners has begun its crescendo, and it’s as underwhelming as it is destructive. But where is the park?

It’s important to note that the Dallas Floodway is a federally funded public safety flood control structure before it is anything else. To date, the Army Corps of Engineers has rejected the plans for the park presented by the city. Additionally, there are federal plans to extend and improve the floodway, and those plans have timelines that have yet to be solidified. The truth is that no matter what the boosters, developers, or their PR teams say—they are far from breaking ground. Ceci n’est pas un park, only the floodway and some renderings. All the while, it has proved to be quite profitable. Is this investment in fiction a vapor-ware brand of development? It’s a very Dallas sentiment to fake until you make it. Perhaps the innovation in this case is to fake it and never make it.

[1] Simmons made a great deal of money through his investments in heavily polluting, old-line industrial conglomerates and a West Texas nuclear waste dump. He was known for his sizable contributions to Republican campaigns and in a provocative interview in the Wall Street Journal called President Obama “the most dangerous American alive.”

[2] Larry Polk, “The Trinity Project: Characteristics of a River,” D Magazine, October 20, 2016, https://www.dmagazine.com/frontburner/2016/10/the-trinity-project-characteristics-of-a-river/.

[3] Jim Schutze, “Park Friends Group Wants To Be Development Czar Along the River,” Dallas Observer, May 11, 2020, https://www.dallasobserver.com/news/more-trinity-river-idiocy-11910221.