The American South holds archetypes and stereotypes alike. Artists in the region help to differentiate the two, jumping the chasm between expectation and reality through representation and portraiture. The flat, limited perspective offered by a stereotype wields more power than it ought to. Its simplicity easily affords ubiquity. In contrast, archetypes can be reimagined and strengthened through complexity and replication. These categories are not tidy, but their variation recalibrates a character. An archetype can be formed through iteration as it expands, complicates, and deepens a figure, allowing for greater authenticity.

Artists in the South often engage with archetypes: Hernan Bas considers the portrayal of the artist and the depiction of queer people; Jill Frank reframes the universal-but-somehow-unique experience of being a young person; and Rahim Fortune asks questions about American identity.1 While Jungian psychology or Joseph Campbell’s The Hero’s Journey (1990) might further illuminate the psychological utility of the archetype, for me, archetypes are useful precisely because they evolve.

In the lexicon of cultural figures, one particular character finds me over and over again: the Southern lawyer.

Portrayals: The Bad Guys and the (Supposed) Good

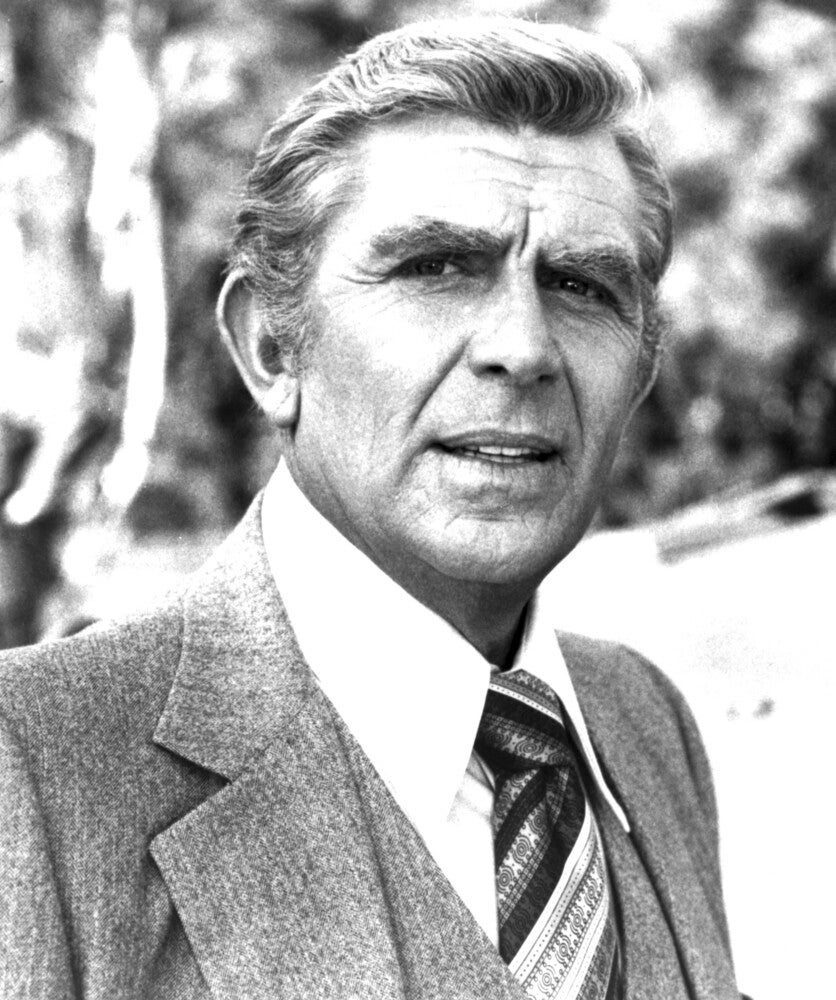

It’s not just me. The Southern lawyer is inescapable in media. He can be found sauntering in a courtroom or pouring over case files atop an executive desk. Serial procedurals, who-done-its, mysteries, true crime, airport novels, and books that became films, or true stories that became books that then became films—all trade in the figure. The Southern lawyer has been adapted again and again. The vast majority of these characters are male, white, Christian, cisgendered, and straight. The figure is often a do-gooder trying to make things right for those he understands to be less privileged than himself. In the hyperbolic version, there are suspenders, a thick drawl, and colloquialisms that are hard to parse. Examples include Chris Kattan’s satirical, incomprehensible character Suel Forrester from Saturday Night Live, or tempered but no less adoptive, Andy Griffith as Ben Matlock, a high-paid Atlanta criminal defense attorney in the television series Matlock (1986–95).

Notably, not all Southern lawyers are on the side of the little guy or are morally upright themselves, but even those that step outside of presumed ethical fortitude preserve conventions. True crime offers up iterations like real-life lawyer Dick DeGuerin, a high-profile Texas attorney who defended New York real estate heir Robert Durst (known for muttering on a hot mic: “I did it, of course”) in two murder trials more than ten years apart.2 DeGuerin won an acquittal in the first trial in his home state, and received a conviction in the second in California. Some Southern lawyers become defendants themselves, like prominent, now disbarred, South Carolinian lawyer Alex Murdaugh, the subject of many documentaries and Dateline episodes, who is serving consecutive life sentences for the death of his wife and son along with financial crimes that continue to grow.3 Murdaugh’s murder charges were adjudicated in a courtroom in which he had regularly argued and a portrait of his grandfather, a well-known solicitor in the area, had hung—though it was removed for proceedings.4 The Southern lawyer has a literary, and at times, familial lineage.

Perhaps the most prolific purveyor of the Southern lawyer is John Grisham. Grisham attended law school at the University of Mississippi in Oxford, practiced law, then served in the Mississippi House of Representatives, before turning his attention to writing legal thrillers. Grisham’s books, which address the American judicial system, are primarily set in the Deep South. The titles, aimed at a broad readership, are too many to list but the plight of the Southern attorney continues throughout his oeuvre. Further propagating the figure, some of Grisham’s stories have been adapted to screen.

A couple of examples: Grisham’s first book, A Time to Kill: A Jake Brignance Novel (1989), centers on its title character, a young Mississippi lawyer who Grisham said is based on himself, as he works on the capital murder case of a Black man accused of murdering his daughter’s white supremacist rapists. Brignance is played by Matthew McConaughey in a 1996 film based on the book. The Rainmaker, a 1995 book and 1997 film, tells the story of Memphis law school grad Ruby Baylor, played by Matt Damon, who files a civil suit alleging corporate health insurance fraud on the behalf of a dying boy and his parents. Whether opposing the biases of the judicial system or corporate greed, Grisham’s figures typically reinforce heroic tropes.

Looming behind these many characterizations is Atticus Finch. Finch is a lawyer of fictional Maycomb, Alabama, depicted in Harper Lee’s To Kill a Mockingbird (1960), and played by Gregory Peck in the 1962 film adaptation. One of the earliest depictions in cultural memory, Finch is a character that galvanizes the scope of this archetypal representation. Originally assessed as the moral father figure, Finch is regularly quoted for saying, “You never really understand a person until you consider things from his point of view . . . until you climb into his skin and walk around in it.”5 Based on Lee’s own father, Amasa Coleman Lee, a lawyer in Monroeville, Alabama, this figure, like many, points to the blurring of truth and myth when a real person predicates a fictional manifestation.

The novel has remained controversial but the reasons for the controversy have evolved over time. It was initially challenged because its address of rape was considered “immoral,” but more recently, in 2023, its use of racial slurs and depiction of a woman making false accusations of rape were cited as reasons for the book’s banning in public schools.6 Today, Finch’s character has also been read as patronizing and racist, while other scholars have emphasized that the book centers a white perspective, leaving out Black voices entirely.7 More than sixty years after its release, the book regularly makes the American Library Association’s top ten most challenged book list.8

Renewed questions around Finch’s character arose in 2015, when a new/old manuscript by Lee was “discovered” by her lawyer. In the posthumously published Go Set a Watchman (2015), Finch is revealed to be a member of the White Citizens’ Council and an opponent of the Brown v. Board of Education of Topeka ruling, which overturned segregation. The follow-up novel shocked readers who had revered Finch as a pure, righteous character.9 Compounding the inquiries into the book’s content, there were also doubts cast about the rights to its publication. It was believed that Lee, who had only ever published the one novel and who died in 2016, was in ill health at the time and may have been unable to give consent to the manuscript’s release.10 Finch’s character hung in the balance of these contradictions. Who was Finch really? And who did Lee conceive him to be? Could these differing views testify to continuity rather than contradiction?

The ethical considerations around authorship, artistic legacy, and intellectual property remain (and it is not lost on me that this second Atticus was brought to light by the act of a potentially dubious lawyer), but the controversy also highlights the fraught, misattributed reverence for Finch, and subsequently, the overly romanticized archetype that he begets.

Whether an expression of society’s good or bad, the aforementioned examples reflect a common fate for the Southern lawyer: as a tool or exemplar of morality (or its absence).

Iterating the Character

Rejecting the flattening that some media promotes, there is an opportunity to expand upon a limited notion of the Southern lawyer. In this case, varied examples reveal not what is new, but what was already there within this familiar figure.

Let me iterate:

Avery Keene, a young Black woman, is the protagonist in the thriller novel While Justice Sleeps (2021). She is a Supreme Court law clerk in Washington, D.C. who works for an ailing, or poisoned (gasp), liberal justice and is sent on a quest to save his life and the sanctity of the courts. Implementing law at a national level, and outside of a trial court, Keene gives insight into procedural logic, even defining legal terminology, an insight that is rare in this genre. In doing so, she depicts legal philosophy without the expected, theatrical “gotcha!” moment on the witness stand. This bold protagonist is a proxy character for the author, voting-rights advocate, and politician Stacey Abrams.11

David Rudolph is the real criminal defense attorney for Micheal Peterson, a wealthy writer accused of killing his wife, Kathleen Peterson, in Durham, North Carolina. Rudolph was featured in The Staircase (2004–18), a thirteen-part docuseries from French filmmaker Jean-Xavier de Lestrade.12 Rudolph, who attended NYU’s School of Law and practiced in New York prior to relocating to NC, did not rely on folksy charm and was contrasted by the distinct accents and local context of prosecutors Jim Hardin and Freda Black. In the documentary, Rudolph was called “very slick” and “very oily,” causing possible distrust in the NC jury.13

Fred D. Gray is the real-life civil rights lawyer depicted in Ava DuVernay’s Selma (2014).14 Often, representations of civil rights attorneys are left out of the lexicon of Southern lawyers, but they are fundamental to the history of law in the South. Gray provided legal counsel to the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People (NAACP), fought on behalf of voters’ rights, and was an attorney for the victims of the Tuskegee Syphilis Study.15 Portrayed by Cuba Gooding Jr. in Selma, Gray argues on behalf of the Southern Christian Leadership Conference (SCLC) and Martin Luther King Jr. in order to march from Selma to Montgomery.

The Southern lawyer is not singular, but plural. Stepping aside from presumptions of the white man born and raised the region, or a codified trial attorney, fiction and reality can ground and contextualize the trope in order to achieve greater reality, greater complexity.

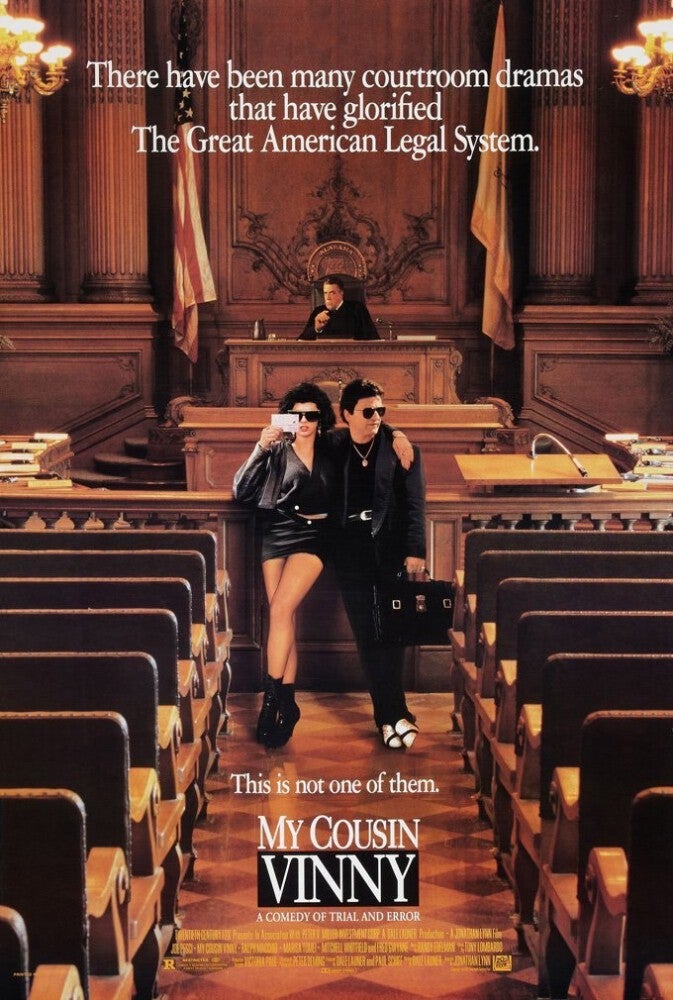

While this compendium recalibrates the Southern lawyer, perhaps the most overt, comedic callout of the character worthy of additional exploration is Joe Peschi’s performance as Vinny Gambini in My Cousin Vinny (1992).16 The film, anecdotally lauded by attorneys as an authentic depiction of courtroom procedure, speaks to how a Southern lawyer is not found but made.

Making a Southern Lawyer

Filmed in Montezuma, Georgia, but set in the fictional Beechum County, Alabama, My Cousin Vinny follows Vinny Gambini, an Italian American personal injury lawyer and Brooklyn Academy graduate, who finds himself in small-town Alabama to defend his wrongfully accused cousin in a murder trial. The stakes are high as capital punishment remains the law of the land.17 Gambini, who has never argued a case in court, navigates legalese and Southern social customs for the first time in a classic fish-out-of-water tale. The new attorney is accompanied and eventually saved in court by his clever girlfriend, Mona Lisa Vito, played by Marisa Tomei who won an Oscar for the role.

The central conflict in the film rests on the fact that Gambini does not embody the Southern lawyer. From the judge to the locals at the pool hall, suspicion of outsiders is found throughout. When Gambini goes to Judge Chamberlain to receive permission to temporarily practice law in Alabama, the judge responds, “You being from New York might have the impression that law is practiced with a certain informality here but it isn’t. . . . Don’t think being from New York you will get special treatment. You won’t.”

The solution, Gambini learns, is to strategically assimilate. Realizing the importance of interpersonal relationships, Gambini befriends the prosecutor in the case, even participating in what could be considered a Southern “boys club” pastime: hunting. Jim Trotter III, played by Lane Smith, fully embodies the conventions of the Southern lawyer: He has the accent, the polite mannerisms, and most importantly, the political connections and know-how. He is Gambini’s perfect counterpoint. Gambini, on the other hand, has to ask what grits are and regularly confuses the small-town community with his unfamiliar ways.

Costuming illustrates how Gambini’s qualifications are arbitrated. The first day in court Gambini wears all black, including a black leather jacket, gold jewelry, and black leather cowboy boots, which he jokingly acknowledges might help him fit in. The judge chastises Gambini for his outfit, claiming he needs to appear “lawyerly” in the future. After repeated offenses, the judge pronounces Gambini in contempt of court for his attire. Later, Gambini takes the judge’s commands to wear a suit “made of cloth” literally and appears in court wearing a red velvet tuxedo. In a nod to the (c)overt code switches often required in such scenarios, Gambini dons a casual Yankees T-shirt outside of the courtroom—“Yankee” representing both Gambini’s home team and his status as an outsider in the South. The power of clothing and social customs on display in the movie makes a case for how a lawyer should appear, and further, who could or should be a lawyer to begin with.

Gambini and Vito exonerate the defendants by implementing their knowledge of the region. Gambini disproves the witness’ testimony by pointing out that stovetop grits cannot be made in less than twenty minutes, a detail on which the testimony rests. Vito, in a triumphant moment on the stand, reexamines a crime scene photograph to accurately identify the tire tracks left in the “Alabama mud” as a vehicle different than that of the defendants. Gambini and Vito combine their personal expertise with a newfound understanding of place. My Cousin Vinny’s reversal of the Southern lawyer trope comes when Gambini victoriously applies state law and navigates the social landscape, not in spite of, but because he was an outsider.

Fiction Meets Reality

There is no clear delineation between stereotypes and archetypes. Stereotypes are difficult to combat precisely because they concede to prejudice rather than evidentiary reality, prioritizing an exterior point of view over shared experience. Yet, examples help distinguish and parse the two. Archetypes are strengthened and altered by the many. An amalgamation of anticipatory desires, systemic failings, false portrayals, short-sighted perception, and at times, real people, the Southern lawyer is a capsule, a projection of the judicial system itself. It never was one type of person. Reading about Avery Keene’s discovery, or watching Vinny Gambini’s cross examination, attests that the characterization and the character itself must evolve. The effect of the evolution of these fictional characters is that a fallible, complex understanding develops—an understanding that perhaps transfers to agents of the court that one might meet during the inevitable summons of (nonfictional) jury duty.

The Southern lawyer is not singular, but plural. Stepping aside from presumptions of the white man born and raised the region, or a codified trial attorney, fiction and reality can ground and contextualize the trope in order to achieve greater reality, greater complexity.

[1] For more on this work, I recommend: Bas’s show The Conceptualists at the Bass Museum of Art in Miami, an exhibition of queer portraits of conceptual artists; Frank’s photo-documentation of cotillions and talent shows, which address children’s formation of selfhood; and Fortune’s photobook Hardtack (2024), which grapples with coming-of-age traditions and the iconography of the cowboy.

[2] See The Jinx: The Life and Deaths of Robert Durst, directed by Andrew Jarecki (HBO, 2015); and The Jinx: Part Two, directed by Andrew Jarecki (HBO, 2024).

[3] Nicholas Bogel-Burroughs. “‘Murdaugh Murders’: What to Know about the South Carolina Mystery,” New York Times, September 20, 2021, https://www.nytimes.com/article/murdaugh-murders-alex-paul.html.

[4] Ted Clifford and John Monk, “Portrait of Alex Murdaugh’s grandfather will be removed for murder trial, SC judge says,” The State (Columbia, SC), June 3, 2023, https://www.thestate.com/news/local/crime/article269830032.html.

[5] Harper Lee, To Kill a Mockingbird (1960; repr., New York: HarperCollins, 2010), p. 48.

[6] Becky Little, “Why To Kill a Mockingbird Keeps Getting Banned” History, May 10, 2023, https://www.history.com/news/why-to-kill-a-mockingbird-keeps-getting-banned.

[7] Laura Marsh, “These Scholars Have Pointed Out Atticus Finch’s Racism for Years,” The New Republic, July 14, 2015, https://newrepublic.com/article/122295/these-scholars-have-been-pointing-out-atticus-finchs-racism-years.

[8] “Top 10 and Frequently Challenged Book Archive,” Banned & Challenged Books, American Library Association, accessed January 11, 2025, https://www.ala.org/bbooks/frequentlychallengedbooks/top10/archive.

[9] Nina Martyris, “Good Atticus, Bad Atticus”, The Paris Review, January 18, 2017, https://www.theparisreview.org/blog/2017/01/18/good-atticus-bad-atticus/.

[10] William Giraldi, “The Suspicious Story Behind Harper Lee’s Go Set a Watchman,” July 13, 2015, https://newrepublic.com/article/122290/the-suspicious-story-behind-harper-lees-go-set-a-watchman.

[11] Abrams is an attorney, a 2016 Georgia gubernatorial candidate, and an important figure in contemporary American politics. Prior to creating the ongoing series around Keene, Abrams wrote romance novels, many of which had legal backdrops, under the nom de plume Selena Montgomery.

[12] Rudolph was played by Michael Stuhlbarg in the recent fictionalized HBO series The Staircase (2022).

[13] Peterson was ultimately convicted and Rudolph remained connected to the case until Peterson was released in 2017 with an Alford plea and time served. An Alford plea is a guilty plea in criminal court in which the defendant does not admit to a criminal act and asserts his innocence but accepts the sentence. See The Staircase, episode 7,”The Blowpoke Returns,” directed by Jean-Xavier de Lestrade, aired January 23, 2005, on Canal+.

[14] Selma, directed by Ava DuVernay (Pathé, 2014).

[15] “Fred D. Gray,” ALMD United States District Court Middle District of Alabama, accessed January 12, 2025, https://www.almd.uscourts.gov/oral-histories-profiles/fred-d-gray.

[16] My Cousin Vinny, directed by Jonathan Lynn (20th Century Studios, 1992).

[17] Capital punishment continues in Alabama and throughout the South today.

This essay is a feature release of Burnaway’s 2024 theme series Twang.