In the summer of 2008, artist elin o’Hara slavick flew into Hiroshima. It was the first time she’d been to Japan. Raised in a radical leftist family, slavick stood vigil on Hiroshima Day with her parents and siblings in the town square of Portland, Maine, where she grew up. They’d assemble there every August 6 in commemoration of the 1945 atomic blast. From the beginning, slavick’s trip was tinged with the valence of pilgrimage. Arriving at the site of the originary ground zero was the first of several performative gestures that would serve as the conceptual underpinnings of the work she ultimately produced there.

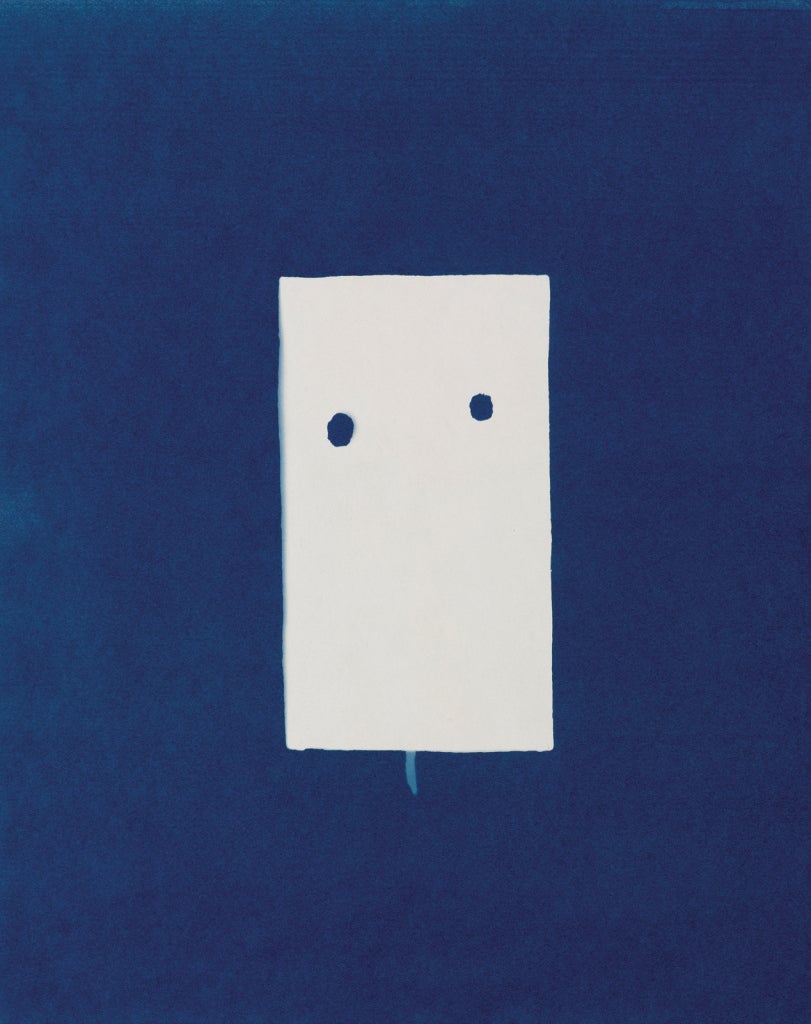

slavick traveled to Hiroshima with her husband, epidemiologist David Richardson and their two children. They settled into the military and scientific research dorms of the Radiation Effects Research Foundation (RERF), previously the Atomic Bomb Casualty Commission (ABCC), where Richardson was engaged in radiation research. slavick immediately embarked on the production of a new body of work that found form in her book After Hiroshima (Daylight, 2013, with essay by James Elkins), a series of cyanotype photograms of A-bombed objects from the Hiroshima Peace Museum archive, photographic prints of on-site rubbings and auto-radiographs (produced by placing A-bombed artifacts on x-ray film to register radiation). The work hinges on a semantics of luminous exposure, a self-reflexive mode of production whose facture quietly resonates with the ineffable horror of annihilation wrought from the unleashing of the atomic bomb on the people of Hiroshima (and later Nagasaki) in 1945.

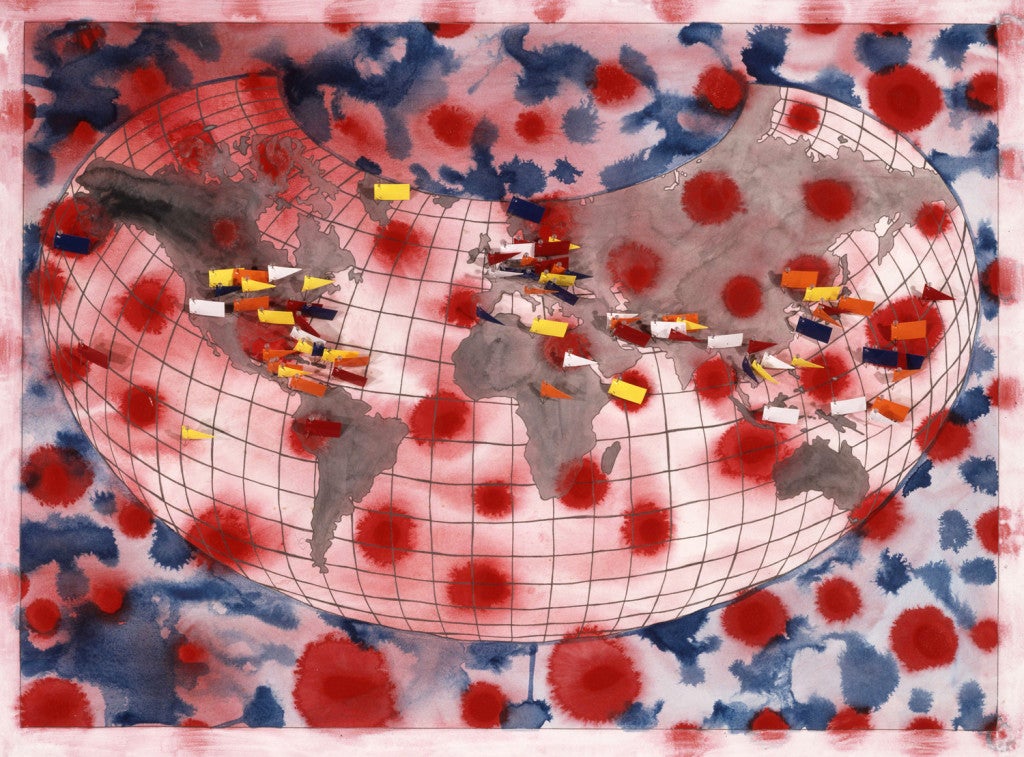

slavick has been a professor of art at the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill for over 20 years and has exhibited all over the world. Her previous book, Bomb After Bomb: A Violent Cartography (Charta, 2007, with an introduction by Howard Zinn and essays by Carol Mavor and Catherine Lutz), was a compendium of watercolor drawings depicting cartographic representations of global bombsites, exclusively those rendered by the United States.

Amy White: I want to talk about this idea of the “after” in After Hiroshima—the linguistic/conceptual construct of After Hiroshima—which you discuss in your essay and which for me has been at the center of this body of work. There is this idea of you, a contemporary artist in the new millennium, talking about 1945, which constitutes a temporal rupture. It’s a claim about what history is—and what Hiroshima was and is—and by bringing Hiroshima front and center in your work, you’re establishing this temporal rupture, pointing to a before and an after.

On the function of time in your work, James Elkins writes: “The shadow cast by the sun onto elin’s cyanotype paper took ten minutes, and happened sixty-six years after the blast.” Elkins talks a lot about time, but I want to tease it out a bit more. I see this issue of time playing out in a few different ways. I see Hiroshima 1945 as a kind of historical pathology. What happened in Hiroshima constituted a rending of temporal fabric, a shift that hasn’t yet been appropriately or sufficiently responded to—and, because of that, there’s this bending of time. It’s been suspended indefinitely. Hiroshima 1945 is perpetuated, and your bringing it forward in your work brings light to this unresolved condition. And so you serve as a surrogate responder. You are modeling the response, producing works that echo and point to that event.

elin o’Hara slavick: The first thing is—1945 and the legacy of Hiroshima—how can you ever properly respond to it? Even when attempts are made to provide a response, is it enough? The Smithsonian Institution initiated an exhibition on the subject in 1995, but it was cancelled, censored. They only hung the Enola Gay plane. They were going to show pictures of the atrocities, but they didn’t. But even if that show had gone on and there were multiple attempts to fully respond to it—working towards a true nuclear moratorium and stopping all nuclear weapons—there would still be this gargantuan shift or bending of time. Because everything is post-Hiroshima. It’s the post-nuclear age. That was the first atomic bomb dropped in wartime against people. You can’t go back and you can’t take it away.

As for this concept of temporal rupture, I think it is fascinating because I had never thought of my work in terms of time per se. I thought about it more in terms of exposure. The cyanotypes and the autoradiographs definitely require exposure time. Elkins talks about how an A-bombed object is eternally an A-bombed object. It functions outside of time; it is a timeless object. These objects were exposed to radiation from the A-bomb in 1945 and still hold some radiation. I always felt that everything in Hiroshima was post-nuclear, that the city itself was an A-bombed artifact, even if that isn’t literally true. But then to take an A-bombed artifact and to place it for 10 minutes in the sun as I do with the cyanotypes—that is another exposure.

When you look at an A-bombed bottle, if it isn’t deformed, you can’t tell if it is from 1945 and that it was exposed. How do you make visible the invisible? How do you talk about those 100,000 people who died or the entire city that disappeared? It’s like that in all wars, but not on the same scale as Hiroshima, right? Then we need to consider the long-term effects of radiation or the implications for radiation exposure today: in Fukushima the rate of childhood cancers and leukemia is huge. Radiation is invisible. You don’t see it.

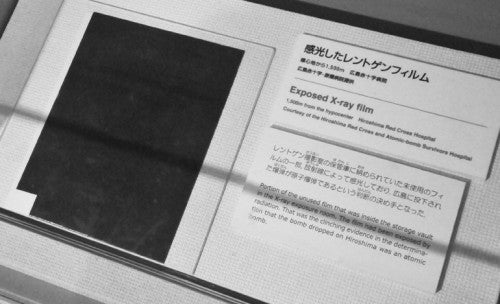

When the bomb was dropped on Hiroshima, there was a vault where X-ray film was kept. It was only when the survivors pulled the film out of the vault and saw that it had been exposed that they knew it was an A-bomb. That’s how the Japanese proved to themselves that it really was an atomic bomb. Because they weren’t told. Nobody knew it was an atomic bomb until quite a while after it was dropped. So the moment when the Japanese discovered that the X-ray film had been exposed is just fascinating to me. In my auto-radiographs, I’m exposing A-bombed objects to X-ray film to prove that there is still lingering radiation. I developed this work before I even knew about that part of the history. I don’t know how that is tied to time—except that it’s kind of eternal. Irradiated objects are described as having a “half-life.”

AW: You’re marking the cataclysm of Hiroshima by dealing with it in your work. You’re marking it now. It’s not topical art, per se. It’s not of this moment. Or it’s of the moment in a different way. It’s an extended, unfinished moment.

es: Yes. Hiroshima 1945 sets the stage for so much in the present. That’s why I think understanding history is so important. I remember a student asking me, “Why aren’t you making work about contemporary issues?” I have and I do. My bomb drawings were rooted in the present. The first one I did was of a bombing in Bagdhad that had happened that day, which is as current as one can get. But, for example, the use of uranium-tipped missiles in Iraq, Iran, Kuwait and elsewhere happened because of the research that was done on Hiroshima and Nagasaki. All wars are linked. And so to say Hiroshima isn’t contemporary isn’t true—of course it is. There are 30,000 nuclear weapons in the world right now, aimed at whomever. There’s still nuclear testing being done. There are still people who are sick, and in Hiroshima there are still survivors. What happened generations ago can totally affect what’s happening today.

AW: I keep coming back to this performative aspect of your work—the mode of facture, exposing A-bombed objects on cyanotype paper in the sun, placing the objects in dark rooms on X-ray film to register the presence of radiation, taking rubbings on site in Hiroshima—these aspects of your work read to me as performative, and in your work I see a relationship between performativity and political activism. The performative action of you producing these works functions as a generative political statement.

es: I also think it’s important that it’s specifically me as an American, going to Japan 65-plus years later, just like the bomb went to Japan from America. And it’s not reparative; truly, I can’t repair anything. But in some ways, that is my ideal. My utopic vision is that I can somehow make it better, or I can apologize, although I know that reparations can never be fully made. But, on the other hand, the fact that I have built these relationships with people there and have gotten to know the people at the World Friendship Center and the Peace Museum or talked with people all over the world about Hiroshima is really incredible in some ways. At its core the work is about going to Hiroshima in peace and not in war. That might sound trite or cliché, but it is also a foundation of the work.

AW: And the performative aspect—there’s this aspect of surrogacy. You arrive on site in Hiroshima. You gain access to the archive of A-bombed objects at the Peace Museum and engage in acts of luminous exposure with those objects, producing artworks that subtly reverberate with the originary blast. Through this process, you serve as witness for us as viewers. These actions connect us to a time and place and point to a cataclysm that remains unresolved. All of these elements are part of what make up this body of work – beyond image.

es: Definitely. I love this idea of “beyond image.” I sometimes feel as if this work is not truly my work, but rather it is alive alchemically, autonomously. I suppose this is due to the nature of photographic processes and the significant historical content, but it is also due to the fact that I have shared this work with as many activists, scientists, historians, and global citizens as I have with artists. The art/image world can be so insular and superficial. Hiroshima reverberates and ruptures, demanding constant attention, witness and response.

Amy White is an artist and writer based in Carrboro, North Carolina, where she contributes to Indyweek, Art Papers, and other publications. She has received top honors for her arts criticism from the North Carolina Press Association and the Association of Alternative Newsmedia and was recently selected to participate in the Art Writing Workshop, a partnership between the International Association of Art Critics (AICA) and the Arts Writers Grant Program, supported by Creative Capital and the Warhol Foundation.