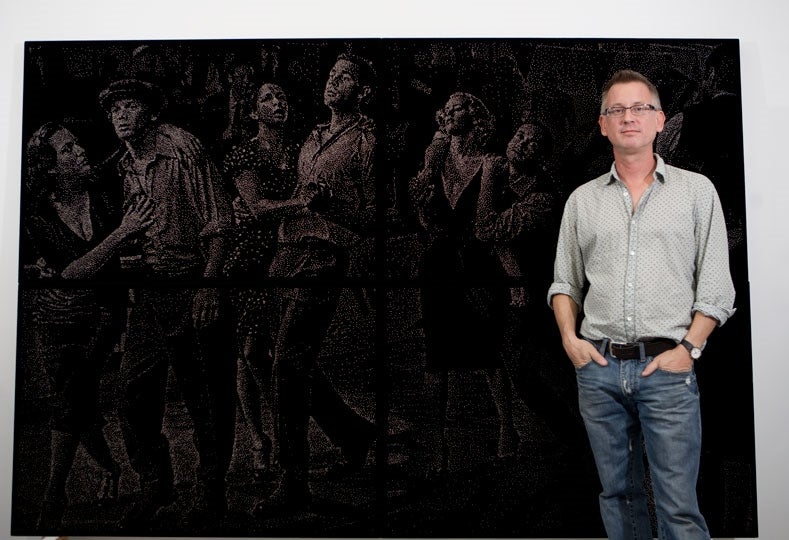

Jon Field (b. 1963, Manchester, England) is the sort of artist who would do something as painstaking as make 8-foot images by pressing 10,000 steel pins into stark black backgrounds. His wide-ranging thoughts spoken aloud with a quick Mancunian accent – the perfect vehicle for his natural sarcasm – hint at an overactive mind and, more often than not, over-caffeination. But, as we sit for an interview, his jitters subside. He pours tea from an unfussy stone kettle as a breeze cuts the sluggish Savannah afternoon and causes his terrace garden’s flora to sway. Restlessness yields to quiet reflection, and a moment of Zen bubbles through our brisk and meandering conversation.

Like his mannerisms, Field’s practice oscillates between restlessness and reflection. To create his handmade photographs, he sources images from the Internet and, using thousands of pinheads that act like tiny mirrors, replicates them at a scale that spans a viewer’s field of vision. Ambient illumination sets finished compositions alight; forms hover in a haunting glow over the picture plane. Reflections cast in reflections aptly describes them, but their glimmer and grace belie a laborious process and its effects: pricked fingers, a sore back, and tired eyes from hours spent squinting at and handling the thousands of pins.

As he devotes nearly a year to a single artwork, time inevitably comes up in any discussion of his practice. When I interviewed him in May, our conversation wound around a few themes: oscillation, distance, time, resistance, humor. We spoke about the meaning he assigns to his art’s distinct, months-long labor:

Jon Field: I believe art functions as a foil. When I make one of them – all that time making art, one work of art – 6,000 hours, those 10 months on one image, I see it as a mode of resistance. That’s 6,000 hours I’m not a cog in a GDP machine, living in a rat race.

Jared Butler: Your time and effort resist that rat race’s short-term logic. The objects take a long time to make, there’s a lot to look at, there’s a lot to know about the images. It’s clearly a struggle against immediacy and inattention, but it’s subtle – the artworks aren’t overtly polemical.

JF: Slowness is important. Not only that it takes almost a year to make one, but the innumerable pins at a large scale – I want viewers to take their time. It lets you interrogate one image, which we rarely do with the thousands that bombard us every day.

In June 2015, we met at his home in Savannah to talk about The Race (2014), which was at the time the most recently completed member of the series End Time. It reproduces a photograph of Lance Armstrong competing in the Tour de France. He maintains a short lead over Jan Ullrich, the 1997 Tour victor often called “eternal second” during Armstrong’s unprecedented seven-title run. Like all the series’ objects, its four panels, bolted together, are each composed of high quality black velvet affixed to foam board and a frame support.

Field’s manipulation of pin density and velvet ground achieves impressive detail with a remarkable level of value modulation. Life-sized, Armstrong and Ullrich threaten to race beyond the picture plane. In their wake, plush fabric peeking through intervals of tightly laid pins suggests a valley in the background that gently rolls into hills and snow-capped peaks ascending in the distance. More than convey visual information with fidelity, the artist’s strategic handling of the medium’s physical properties delivers a unique visual experience. Seen in person, constituent materials appear to melt away, leaving behind a spectral afterimage in grades of pure light.

The Armstrong image was not randomly selected; the source photograph illustrated a 2012 online story on Armstrong’s ban from cycling for using performance enhancing drugs. Far from leading Armstrong on a Cersei Lannister walk of shame, The Race complicates judgment. Field pairs his works with captions when they’re exhibited; for The Race, he selected a description of the scapegoat mechanism, referencing anthropologist René Girard’s elucidation of the term: “In anthropological theory, the scapegoat mechanism is triggered when one person is singled out as the cause of a particular problem, and is expelled or killed by the group.”

The excerpt shifts focus from the depicted athletes to the broad framework of professional cycling at the turn of the 21st century. Rather than condemn individuals or their choices, The Race situates specific acts in the context of a hyper-competitive, capital-driven sports world obsessed with celebrity and marred by endemic cheating. To that point, Ullrich was also convicted of doping that year, and his results since 2005 have been removed from record. As Armstrong observed colorfully, “the blood-doping era was like a knife fight where everyone started bringing guns.”

Faulty expectations and delusions fashion worlds of self-defeating deceit in domains beyond competitive sport. Shifting gaze from a sign, gesture, or pose to their fluctuating interpretations – like a pendulum swinging from particular to universal – End Time lays bare how races more global than the Tour de France twist into vicious cycles. Concerned with more than the prestigious Grand Tour, The Race draws insight from fragments left when doping achieves an illicit competitive edge and snuffs out its raison d’être, a hallowed athletic career. Field’s unconventional materials underscore this oscillation between microcosm and macrocosm; like stars in constellations, the relationship of single pin to composition in sum.

You linger, amble, and look slowly when you see Field’s work firsthand. They’re stunning, shiny; you recognize famous people and chuckle. But each photograph Field reproduces has a complicated backstory. Dotted with details of controversy and stretched truths, the scenes are perforated long before pins pierce its lines into velvet panels.

Plucked from visual culture’s maelstrom, enlarged, and broken into a constellation of silver points, the source images’ mimetic insistence succumbs to artful pixilation. Through the negative space introduced as black velvet and steel pin pixels break apart the image’s integrity, stories interwoven even within a photograph of a bicycle race become visible. Here, not only does photographic content break down but, to boot, the photographic medium’s basic ability to map onto reality becomes uncertain. Field’s replication, caption, and call to investigate the image’s backstory reveal the source photograph’s limitations. How much can that source image alone convey about racing cyclists’ intentions, drives, or fears, or about the world they inhabit? Field’s interrogation discloses how a photograph is not an absolute or authoritative representation of a fixed reality, but an imperfect likeness as relative as its content: When it was taken in 2007, the original photograph was meant to illustrate the tale of a venerated athlete’s victory over cancer and domination of a fair sport; by 2012, it became the picture of scandal and deceit.