The studio of Atlanta-based artist Eleanor Neal is covered in hanging bunches of Spanish moss, textured collaged papers treated with beeswax, and canvases the color of sherbet sunsets, with the soothing scent of sage permeating the space. It’s exactly the kind of studio where you would expect Neal to create her distinctive monotypes, paper collages, and india ink drawings that connect the natural world to the frailty of human existence. A virtuoso of expressive mark-making in each plane of her work, Neal often creates these works on her studio floor, in such an intimate proximity to the work that furthers the personal nature of her oeuvre. With a Bachelors in Fine Art & a Masters in Education from Indiana University, Neal recently finished her second Masters in Studio Art at the School of the Art Institute in Chicago, where she focused on work inspired by the Sea Islands of Georgia. I sat down with Neal in her studio at the Goat Farm to discuss our shared interest in the Gullah Geechee history of Georgia, and the importance of the South’s influence in her work.

Much of your work has been inspired by the southern coast of Georgia. I went to grad school in Savannah, and actually spent much of my time there learning about the history of the city and the surrounding sea islands. The Gullah Geechee, a culture that was born out of the freed slave community that maintained much of its African traditions, has shaped much of the cultural heritage in that geographic area. What about the Gullah Geechee legacy & connection to West Africa has inspired you and translates into your work?

My journey with this interest in Gullah and Geechee and moss developed as part of my studies at the School of Art Institute in Chicago, while I was finishing my masters there. I had this interest in the South and the Georgia seacoast, which lead me to my interest in Spanish moss, which as you know covers much of the trees down in that area. I became interested in how the moss holds and contains water, and how it is independent of its surroundings; even if the host tree is dead, the moss still thrives. It has a sense of life within it.

My professor had recommended I look into Julie Dash, and her 1991 book and movie Daughters of the Dust. I watched the film and then read the book, which lead me to visit Ossabaw Island (one of the Sea Islands off of Georgia’s coast where the film takes place). I really wanted to spend time there, getting quiet and getting still, and thinking about what it must have been like for the women who lived on that island during the time the film takes place [early 20th century]. I thought a lot about the mother, the matriarch of that story, who really held the family together, and who had such a strong sense of what the island really represented for them as a people.

At one point in the film, the mother holds her hands out, which are stained blue from indigo dye, and within her hands are small stones. These stones hold power and represent the land, their land. She is surrounded by the women in her family all dressed in white in a deep part of the forest. She sits on a tree stump and talks about the life force and empowerment within and how to survive and how we must hold on to each other. She takes these stones and wraps them in a cloth and then in twine, which Dash learned in her research of this community was a collection and protection of power. The tighter she ties that twine, the more power it holds. This was such a powerful moment for me, a kind of “Ah-ha!” moment, to connect nature and power.

I then traveled all over the Sea Islands, from St. Simons to Savannah to gather and collect the moss. One thing most people don’t know is that if you pull it from the tree, it’s fresh and has no chiggers in it – just don’t take it from the ground. So, I began bringing the moss back with me to Atlanta and Chicago and reflecting on this sense of women and empowerment interwoven with nature.

All of this allowed me to question contemporary issues that I am dealing with today: how we exist; how we [as African Americans] are losing our sense of identity and power, based upon how others treat us. It’s like the Spanish moss – people look at that and think that it is a parasite, that it harms the tree and has no natural purpose – but none of that is correct. It feeds the tree and the tree feeds it; they exist together symbiotically. It’s similar to the human race: we make up these notions and prejudices about others who are different, not like us, because we think they must be there to harm and destroy us.

I look at all of these reoccurring themes within the folklore of the Gullah — this crucial connection to the land and where they are from — and they are all about finding this empowerment within ourselves and not allowing others to take that power away from us.

It’s so interesting that you brought up the Spanish moss. I always had heard that the moss was harmful and shouldn’t be touched. Beautiful, but harmful.

It to me just so relates to what is going on in our world: if only we took the time to know the story, to know the people, things could be different.

So, switching gears a bit to your background: I saw that you got your first degrees from Indiana University, and most recently your MFA at the School of the Art Institute at Chicago. How did you end up in Atlanta?

I’m from Indiana. I would visit my sister down here in Atlanta, since she worked for Coke. It actually took me a long time to explore outside of metropolitan Atlanta; to look at places like Savannah, St. Simons, and Jekyll – there’s so much history there. And once I began to venture out, that’s when it got interesting for me.

I’m from up north as well, from Michigan. I find that as you become an artist in the South, people from up north tend to look at your work in a different way, through a very narrow lens of what they believe the South to be. This is why it’s so crucial for artists to talk about the South in their authentic voice, to continue to create this new narrative of what the South actually means and what it means to be a Southern artist.

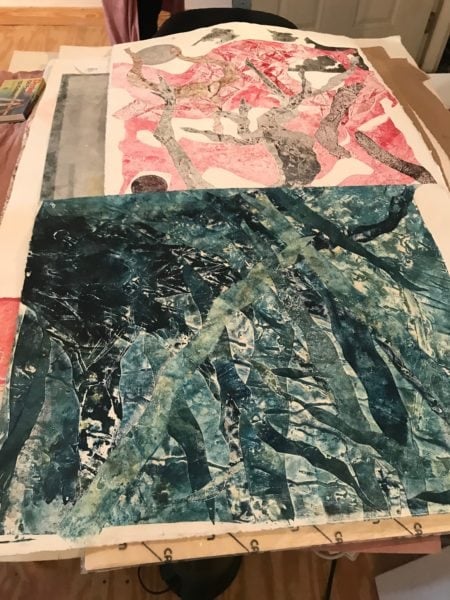

There’s something different here, a different connection to nature. I started with my monotypes, putting moss within the prints. As I began to do more research and delved into the readings, I began to piece together that this is something that I really want to explore. Part of it was out of practicality or even necessity — using materials found around me — but another part of it was what has been going on and is still going on in the South.

I recently got to work with author Fred Moulton while I was finishing my work at Chicago, and he has this argument that our outside and inside worlds are becoming more involved with one another, and how this can be a dangerous thing. He points to instances of police brutality, when people are attacked in their own homes, of this outside world invading their inside space, and I drew so much inspiration from that through my work. I deal with outside, natural materials, and bring them inside my studio, working with them in an intimate space, often standing over them as I work on the floor. And I felt this congruent theme that both he and I were talking about with our work, about how power is connected with space, and how the outside world can look at your interior space as a threat. So much of this is felt here in the South, with the history that prevails here more than other parts of the country.

But the inspiration from the Gullah Geechee stories has been prevalent as well. I think of the story of Ebo Landing, where recently arrived slaves turned back to the water and drowned themselves together rather than face life as slaves, and this has been something I’ve been sitting with and exploring for a while. They believed they would travel through the clouds and go back home to Africa. How would it be to be able to leave the earth and move through the sky, as they believe? So, I’ve been exploring this connection between the earth and sky and thinking of it as a natural human journey. I wanted to make these canvas works that had so much light in them that it almost felt like they would float away into the clouds.

What’s next for you?

I finished a residency last year in Vermont and have been working on some pieces from that. I really lucked out with that residency because I was in this beautiful old building in the woods, on the bottom floor with three large windows. It got so dark at night there, a deep blue dark, and I could hear the water outside as it hit the rocks surrounding the lake. It was a conversation that I was hearing between different forces of nature, between the water and the rocks, the earth. I also was inspired to start working with dye, going back to my Gullah research and the prevalence of indigo. So, I’ve been working with dyes and stains, with the natural folds that occur when you dye fabric and fold it, letting nature assist in the process.

In June, Neal will be working with the College Board in Salt Lake City, Utah, as part of a group exhibition at the Utah Arts Alliance.