Stacy Bloom Rexrode relocated from Boston to Chapel Hill, North Carolina, in 2011. She is a recent MFA graduate of the University of North Carolina at Greensboro. I first saw her work in “Surface Matters,” a three-person exhibition at the Block Gallery in Raleigh, and, attracted by the eco-feminism present in her work, visited her in Greensboro and saw her thesis exhibition at the Weatherspoon Art Museum in May. She will begin to teach art history at Alamance Community College in the fall and is seeking gallery or museums with domestic settings to show her most recent installation Quasi-Delft Bequest.

Shana Dumont Garr: I was first drawn to the sculptural use of artificial flowers in your work. Do flowers hold any particular meaning for you?

Stacy Bloom Rexrode: When I was a child, I lived on an Army base in Frankfurt, Germany. I remember visiting fields of seemingly endless tulips in glorious colors in the Netherlands, and seeing many wildflowers in the countryside. My father died when I was 10, and the fragrance of the flowers at his funeral remains with me today. These childhood memories greatly impact my work.

SDG: What about the rich symbolism that comes along with flowers? How much is art history on your mind when you’re working?

SBR: For my recent still-life floral sculptures, I saved my family’s recyclable plastics for one month and then modeled them into the style of Dutch still-life paintings. These were popular in the Netherlands at the onset of horticulture and bulb production. The bulbs were so expensive that people couldn’t afford them but, ironically, everyone could afford the paintings. So everyone had paintings but no real flowers in their homes. In the future, this may also be the only type of flowers we have.

SDG: In addition to enameled silk and hand-sculpted plastic flowers, your recent work contains zip ties, paper plates, and plywood. Why do you use these nontraditional materials?

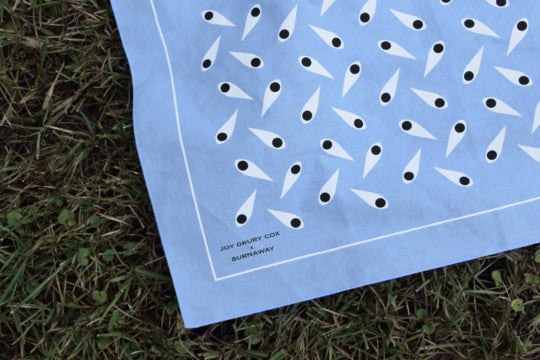

SBR: I use a variety of media to call into question hierarchies of materials, such as bronze being considered more valuable than plastic. I’m interested in reducing false distinctions in the values we apply to craft versus fine art. With my series Quasi-Delft Bequest, I was looking into how Chinese porcelain is derivative of Dutch delftware and thus of lower retail value. I took that devaluation a step further and put as much effort as I could into decorating paper plates with blue ink and implying the question: are these less valuable than porcelain ware?

SDG: It sounds like you’re also tackling issues of evident labor versus ideas the artwork expresses. Do some of the materials you choose force you to “invent” methods and techniques in order to execute your ideas?

SBR: Yes, but I’m a licensed general contractor, so it’s not a stretch for me to use, for example, plywood and steel. With the plastic bottles, I’ve now completed three Dutch still lifes. You can see a progression as the flowers become more complex. My tools include a heat gun and a crème brûlée cooking torch. I had no fingertips left after that!

SDG: Did your interest in flattening the difference between “high” and “low” art and luxury versus throwaway materials become more important to you in graduate school?

SBR: I was fortunate to travel to the Venice Biennale with my graduate program last year. We visited an exhibition curated by Cornelia Lauf, where she invited six or seven artists and craftspeople to produce a new work of art to be shown in this palace. She placed, for example, a piece of conceptual art beside a fabulously constructed wood desk. I loved how the exhibition brought together both types of work. I’ve always struggled with these separations between craft and art, what I consider false distinctions. I carry that through in my material choices, and that’s how this body of work came about.

SDG: You had a residency at the Vermont Studio Center this past December. How did your time there affect your practice?

SBR: I didn’t bring a lot of materials with me because I wanted to let the environment influence what I’d work on. It turns out there is not much in Johnson, Vermont, so I found myself at the hardware store. I wanted to continue my practice of using utilitarian items in a decorative way. My grandmother loved to crochet, and for me, the pieces I made, including Ada’s Family Ties, represent her role as the nurturer and the gathering place of the family. It’s a huge doily design where the shadows play as large a role as the ties, and represent inheritance.

SDG: Your sculptures of the ladies with floral headpieces have perhaps the most overt links to feminism. Would you agree?

SBR: Yes, I wanted to make them as absurd as the idea of the head vases that inspired them. The actual lady head vases were produced in the 1950s as “gentle reminders” of the decorative place women were to have in the home after WWII. They are bizarre—they came with pearl necklaces added after firing. They literally put women on pedestals.

65 by 15½ by 15½ inches.

SDG: And away from whatever workplace they may have found during the war.

SBR: Yes. I gave them huge headdresses of obnoxiously plastic-looking flowers. The pedestals are designed to act as part of the piece. They are made with materials you’d use to build a home such as plywood, cinderblocks, and reinforced steel.

SDG: What are your post-MFA plans?

SBR: Like many recent grads, I wonder how I’ll maintain my focus and the level of production I had during the MFA program. I struggle with the angst of wanting to always be there for my two daughters (ages 13 and 15), and at the same time show them how to go after the thing you really want in life. So right now I’m trying to find that balance, because it really is my role as a mother and the domestic context that feeds my work.

It’s liberating to be able to commit more time to a single project knowing there are no deadlines. I’ve been wanting to continue some of my current works in a much larger scale, and this newfound freedom will allow for that. I also want to continue incorporating the idea of social practice into my work and plan to address women’s issues through participatory installations such as my past work “TAG! You’re It!”, which dealt with women’s reproductive health and rights.

Shana Dumont Garr is a writer, contemporary art curator, and the director of programs & exhibitions at Artspace in Raleigh, North Carolina.