Nikita Gale is an Atlanta-based artist working in an array of media, from the tangible to the more ephemeral. She has a strong character and cites the moment she quit drinking alcohol as the point when she rediscovered art as her creative focus. The self-taught conceptual artist [who is a BURNAWAY board member] will be leaving Atlanta in August to get her MFA at UCLA. I met up with her in her studio at the Atlanta Contemporary Art Center, where we discussed the Atlanta art scene, relationships, being an introvert, strange dreams, how her studio is like a Word document, and how her text-centered artwork is becoming much more performative.

Sherri Caudell: Is the reason for you leaving Atlanta to pursue an MFA purely education driven or are there other factors involved in your decision?

Nikita Gale: I grew up in a military family, and one of the primary conditions of that lifestyle is constantly changing locations. Something I’ve learned about myself as I’ve gotten older is that this part of my upbringing has become an important factor in my sense of fulfillment as an adult. Changing locations, being in other parts of the country or the world and leaving for a while, meeting new people and developing new relationships are all important. It can make the world feel simultaneously bigger and smaller. It’s the sense of wonder that I find really inspiring and instrumental in activating new ways of thinking and creating. So this departure for me is more about making my world bigger. The point of convergence between forward motion and excited discomfort are “my zone.” I’m excited to be returning to a university environment where I can spend two to three years focusing on my work. It’s an important step for me professionally, because I’ve never had any formal art training. I’m excited to see how my work will change in a more demanding environment where everything is more intentional and structured. It’s exciting. I’m excited.

SC: What program will you be attending?

NG: I’ll be enrolling in UCLA’s New Genres program this fall. I was deciding between Yale and UCLA; they are the top two university MFA programs in the country, so there was a part of me that felt like I couldn’t make a wrong decision. In the end, UCLA’s program just made more sense for my work in terms of faculty and departments. It’s also a much smaller and more individually driven program with three students admitted per year, which was another huge plus for me. It was very important for me to go to a university and not to an art school, because I wanted to have the same access I’d have as a university student in terms of research resources and curriculum. Also: Los Angeles. Duh. The Western U.S., specifically Los Angeles, has an amazing historical relationship to conceptual art and also to artists of color. It’s all there.

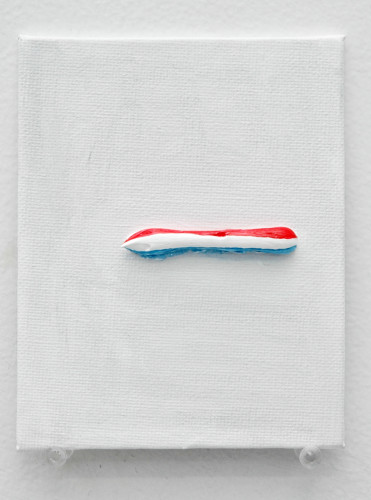

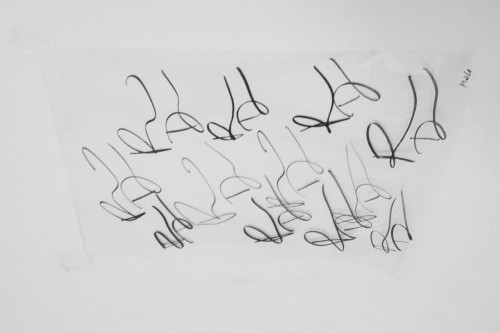

4 by 5 inches.

SC: Do you foresee yourself returning to Atlanta?

NG: I love too many people in Atlanta to say I’m not coming back.

SC: Why do you think you are so driven towards text as a form of artistic expression?

NG: I’m attracted to text because language is endlessly problematic as a form of expression. It’s problematic, and in spite of that it’s a primary form of how we communicate and relate to one another. I’m drawn to the relationship between language and the body. Language is immaterial; this condition of immateriality gets even more interesting when it touches identity. In a way, I see language and text as a means of exploring identity from the inside out rather than from the outside in. I’ve recently become more interested in systems of expression that eschew presence in the physical sense. Presence and appearance and their attributes have been used for thousands of years to categorize and oppress, so I also acknowledge that a large part of my interest in language also comes from a desire to work in a medium that rejects the use of images or figurative representations of the body.

SC: What changes are currently occurring in your work?

NG: My pieces always look different from one another. The work is definitely figuring itself out. It’s becoming more challenging to define, but it’s also becoming a conversation as opposed to something more linear or narrative. The latest conceptual development of my practice involves imagining the body as a site capable of both the production and consumption of identity and considers how identity is constructed in the absence of a physical body. I’m working on a lot of new things and allowing myself to have the space to explore new ideas and to revisit and reimagine old ideas. I think the only consistent elements within my work are less visual and more conceptual.

SC: What have you gained from being in the Studio Artist Program at the Atlanta Contemporary Art Center?

NG: It’s given me a semi-permanent space in which to work. It’s nice to have a studio. It’s like a real world equivalent of a Word document. You can work on something, save it, and then reopen it and everything is exactly how you left it.

SC: I know you were born in Alaska and moved around a lot, so what sparked your decision to move to Atlanta?

NG: Well, I was eight when my family moved here, so I didn’t have much say in the decision, but if I did have any voice in that decision, I would probably still be in Alaska or somewhere on the West Coast.

SC: Coming from a military family, was your upbringing really strict?

NG: It wasn’t super-strict, but I think most military children will probably agree with me that when you’re in a military family you’re constantly being inserted into different social situations. One of the skills that you have to develop is the ability to meet new friends and to deal with a constant influx or cycling of people. It was interesting when my family moved here, right before I turned nine, because all of the kids in school had been together for four or five years. I’m a really shy person, and I was painfully shy as a kid.

SC: That’s funny, because you seem really outgoing.

NG: I feel like it’s a survival tactic. One night, I went out with a friend of mine who was visiting from North Carolina. We went to a couple of openings, and I was introducing her to people, and after we left and had a quiet moment, she was like, “You know something I’ve noticed about you? You’re a shy person. It’s requiring so much energy for you to go out and talk to people.” I’m also an introvert, so I need that rest period of recalibrating.

SC: Do you consider yourself highly ambitious and driven?

NG: I think I have a healthy sense of competitiveness in me. I believe that I can always be better and learn more. I’ve been like this since I was a child, but I’ve chilled out a lot.

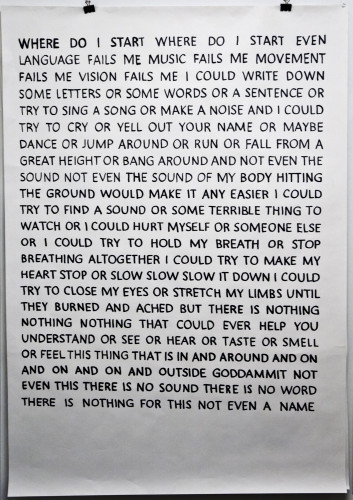

print, 13 by 19 inches.

SC: What was your experience like as an undergrad at Yale University? What were some highlights and maybe some struggles that you encountered?

NG: I met a lot of very smart people and have had some incredible opportunities because of my education. I miss the libraries. At the same time, it’s a very wealthy, private Ivy League institution with its own set of hang-ups relating to socioeconomic and class insensitivity. The administration definitely has a number of “blind spots” when it comes to cultural awareness, but it’s something on which they’re working, I’m sure.

SC: Can you talk about your Sumptuary performance at MINT Gallery and the concept behind it? It was apparently the most successful single-night event of the series.

NG: BL__K ACT___S explored the simultaneous conditions of presence and invisibility experienced by socially marginalized bodies who commonly encounter representations of their lived experience as spectacle. The work itself was an improvisational sound sculpture that functioned as a means of drawing out and investigating precarious instances in which identity is constructed and translated in the absence of—and most times beyond the control of —a physical body to which an identity can be attached. Because of its liminal and fluid characteristics, sound was used as a primary medium for combining and recontextualizing hundreds of popular hip hop songs in concert with audio clips from interviews and films in which specific black actresses were cited.

This work was a consideration of how identity is constructed in the absence of a physical body and how this condition is expressed in everything from music to landscape to architecture to sculpture. This was a really great experience. There was a lot of great energy around it and it was cool to see how people interacted with the music. It got tropical. I had a lot of fun. I didn’t really have any expectations for it. It was just an idea that I wanted to test out. I’ve been branching out into audio and sound performance, and a lot more installation. It was exciting to do something that was just sound based. I think it worked really well with the installation To Hell In A Handbasket [by artist Joseph Bolstad] that was in the space—the hell lights and supermarket baskets and all of that stuff. It was nice to make a piece that still had a concept behind it, but it was also just fun to dance to the music. It became a sort of dance party and got really “real” near the end.

text reads “I feel sure until you have to leave.”

SC: What else have you been up to and what’s coming up?

NG: Earlier this year I had a show at PARMER, a really amazing new art space in Brooklyn. I showed a new series of work, “Autographs,” from April 19 through June 8. I also revisited [my body of work] 1961 and created a new installation based on the initial series that was shown at {Poem 88} in 2012. The show traveled to Los Angeles this summer, where I had a solo exhibition with Reginald Ingraham Gallery. It was exciting for me because I had been really interested in showing in Los Angeles for a while, and somehow the stars aligned and this show happened. The work is now at the Zuckerman Museum at KSU in the “Hearsay” exhibition. I’m happy that the work is still getting so much attention, especially given the amount of time and work that went into creating it. There are a few new elements that tie into some of the work I’ve been doing with sound and installation.

I was also included in the inaugural show at Gallery 72 called “Forward,” and I also have work in a group exhibition in New York called “Rooted Movements” at LMAK Projects, which is up through August 1.

Godarding (Full) from Nikita Gale on Vimeo.

SC: What is influencing the new performance aspect as of your work?

NG: I think the desire to see my work in the world is a major driving force for incorporating certain performative elements into my current practice. Placing yourself within the work in real time can create a kind of anchor that allows the audience to locate itself more explicitly in the work. There’s a sense of commonality that develops in performance that I find accessible and unpretentious. There’s something very seductive about the act of witnessing. At the same time, there’s also a desire to find ways of moving away from the inaccessible and exclusive qualities that often characterize “fine art.” It’s one of the reasons why I occasionally flirt with citation in my work and it’s also the reason I enjoy the work of artists like Jason Rhoades, David Hammons, Andrea Fraser, or even Barbara Kruger and Jenny Holzer. Their work communicates beyond the context of the fine art world; it’s private and public, it’s political but not didactic, it’s humorous but poignant.

SC: What would you change about the Atlanta art scene?

NG: The art scene in Atlanta feels very young, like it’s still figuring itself out. There are all these really exciting things that are being built and developed. There are a lot of cool arts organizations that are popping up and doing really amazing work. I remember being involved with these organizations four or five years ago when everyone was just starting out and no one had any money and people where just figuring out how to make things happen. I don’t know if I would change anything. There’s this scrappy quality to the Atlanta art scene that I think gives you a lot of space to be able to explore and experiment. Anything that I would think about changing would make it resemble some other art scene. Atlanta has a small tight-knit community and everybody is just sort of making things work in the best way that they know how.

The more I think about it, when I go to other cities, people ask me, “What’s going on in Atlanta?,” and it’s easy when you’re here to be really down on it and like “all this stuff is super shitty” and “this needs to be changed,” but when I talk to other people about Atlanta, it’s like “Atlanta’s pretty cool.” I like it a lot, and the level of access that you get to things, like the Glenn Ligon interview I did. As an artist or an arts organizer, there are only a handful of people who are doing what you’re doing. So when you build the reputation of being a person who’s doing a lot of stuff, it’s easy to become one of those go-to people. So, I don’t know if I would change anything. I think Atlanta is pretty awesome. I wish things weren’t as spread out. I think that would be the only thing I would change. There are all these really great arts spaces, but they’re so far away from each other—but that’s a condition of living in a city that’s dealing with urban sprawl.

SC: Do you remember the last dream you had?

NG: Yes. I almost always remember my dreams, and I dream a lot. The last dream I had, I remember Kurt Cobain was there, which is really weird—maybe not that weird. I think he was talking to me. When I did my first residency in Woodstock, New York, I was in the Catskills for six weeks. It was amazing—my body, my mind, everything just felt really clear. I was like “Oh, this is the life,” but then really bizarre things started happening to me after about a week, which was enough time for me to be treating my body a lot better, eating a lot healthier, and making art all the time. I feel like it freed up a part of my brain, and almost every single night I would have a dream and then the next day something from the dream would appear in my waking life. It would be an object, or some kind of image, or somebody would say something or do something—so it was this really crazy déjà vu. It happened for about another two weeks after I came back to Atlanta, but then it went away.

SC: What are your feelings on the concept of love?

NG: It’s a big subject and you’ve caught me at a really interesting time because I recently ended a very intense, brief relationship. The scenario and the way that it happened were very cinematic. It played into these ideals that we have about love, where it really washes over you. You’re in a room and all of a sudden there’s all this crazy energy and you’re like, “Oh, I’m in love. This is what it is, right? It’s like in the movies.” It was super dramatic and I got swept away. It’s nice to have those moments where you can’t necessarily shut your brain off, but sort of go with something that feels very instinctual. But then there’s always that part of your brain that’s saying, “Okay, when’s the other shoe going to drop?”

There are so many different ways that love manifests itself. People use the word in a lot of different contexts. I think it’s possible to be in love with another person. I totally, absolutely believe in it. I feel like it’s a gradual thing. I’ve definitely been in relationships where I liked the person, and as I got to know them I started liking them more. But I’ve also been in situations where I’ve really liked a person, and as I’m in a relationship with them I start liking them less. People always say that love is about compromise, but I don’t know if I agree with that. I think it’s more about understanding or being able to give a person space to be who they are and do the things that they want to do.

Disco Clouds (full) from Nikita Gale on Vimeo.

I think ultimately what happens is that people misconstrue love as something that requires all this sacrifice, which it does to an extent, but not in a way that’s going to make you feel resentful or shitty. I think it should feel effortless, because communication is the most important thing. If you can’t communicate with somebody and you can’t laugh at the same things—that’s a really big problem. This most recent scenario was nice because there was a lot of laughter and it was really fun. We had been friends for a really long time, for about three years. You have to be open to the possibility. No matter how frequently I get beat up by it and disheartened, the belief is always there. It’s one of the most frustrating human conditions—hope, believing in something, even though all of the previous experiences would, logically speaking, tell you to stop. There’s an amazing quote by Alain de Botton that resonates with me: “Once you’ve eliminated all the things that seem like love but may just be psychological immaturity, you might not have anything left.”

SC: What kind of artist do you want to be?

NG: I’ve been thinking about that a lot, especially with grad school coming up, because it’s the moment when a lot of things solidify. I think I want to be the kind of artist who makes work that’s communicating with the real world. There are so many artists coming out of the West Coast, specifically L.A., who make work that feels like it fits into the world, that could make sense if taken out of an art context. That’s really important to me. I always go back to a conversation I had with an arts writer friend, who said something that has always stuck with me: “Art should be used as a tool that provides further understanding for people, a tool that helps you understand the world, or look at the world in a way that you hadn’t previously looked at it or thought about it.” It’s just an amazing, simple thing. So that is kind of my goal, just to make art that can be used as a tool for understanding.

Sherri Caudell, a poet and writer from Atlanta, is the poetry editor of Loose Change magazine, published by WonderRoot.