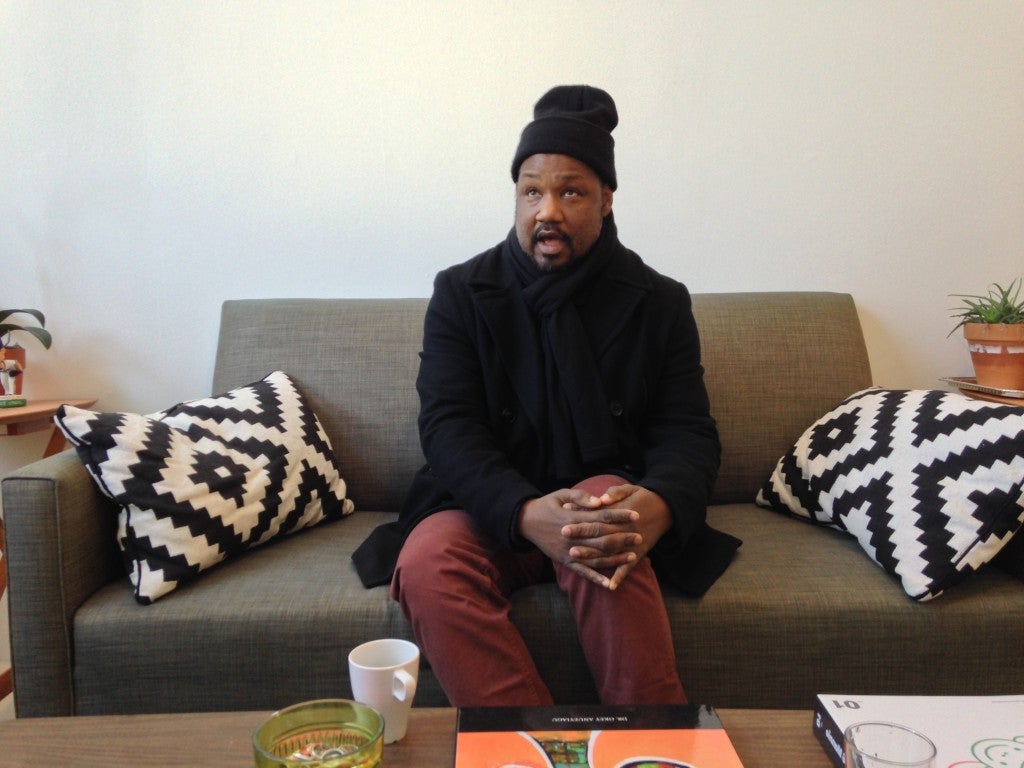

Susannah Darrow: So, you’re from Detroit. What impact did the Detroit Institute of Arts [DIA] have on your development as an artist growing up there?

Steve Locke: It gave me the understanding that art was something I could do, that this is a job some people have. Every school kid in Detroit goes through that museum. For an eight or nine-year-old kid, having access to those things is huge. That was my neighborhood museum.

Darrow: What do you think about the possible deaccessioning of DIA’s collection?

Locke: It’s disgusting. I know there are many layers and it’s complicated. On one side are the people who love that museum, who gave themselves a tax increase to fund it. On the other side, you have all of these bankers who want to get paid. We know from Marx that capital is only concerned with itself. It’s not concerned with people and places. This whole community of artists is completely outraged about what’s going on, and then you have one of the top auction houses [Christie’s] actually evaluating the collection.

That it’s even worthy of a discussion is hugely problematic. There’s a lack of vision and there’s a lack of value. For them, the museum only has one kind of value and that value is monetary. That’s the side you keep hearing about. You don’t hear about the values that artists like Mike Kelley, Carrie Moyer and me—all these people who come from Detroit—that that collection figured prominently in all of our developments.

Darrow: You have a very rigorous studio practice and it very much is your profession. You’ve said it’s your “job” when you go to the studio. Can you talk about the process and role of your studio in your practice as an artist?

Locke: There are two parts of it: the studio as a place and the studio as a way of thinking. Over the past 10 years, my studio was always in my home. So, I could roll out of bed and make a painting. I recently got a studio at the Boston Center for the Arts, so not having my studio in my home really does make it feel like I’m going to work, like I’m going to suit up and drive down to the office, punch in and punch out. That feels nice, actually.

I try to be in the studio every day. Even if I just go to eat my lunch and then go home. I deal with my students all day, so on my way home I go to my studio and think about my work after dealing with theirs all day. You know, you tell students stuff and then you think, “oh man, I should probably do that myself.” [Laughs] So that’s a way of staying honest.

Darrow: Are you more disciplined about how you work now?

Locke: I’m a control freak, so I don’t think it’s possible for me to be more disciplined. But, the separation now is really interesting to me. There are things that I do at home that I have to figure out how to do when I get to the studio. So I have this wacky drawing practice at home now that’s not as complex as in my studio, and on my blog I started using drawings I find in my studio, drawings that explain things. It’s just a very different way of working. What I do in my home now is nothing like the work I do in my actual studio. My studio is no longer a place where I live and work. It’s a place where I work and it’s very hard to leave.

approx. 84 by 49 inches overall.

Carl Rojas: How do you let that go at home in the evening? This stuff is all around us all the time and it’s hard to put it down. Don’t you sometimes at night just want to go, “well, I’ll just do something really quick?”

Locke: I think that impulse is not going to go away because that’s part of my training. But I think the difference is that sometimes I have had really bad ideas that I executed because I had access to the materials. You do it and think: “Well, that was a mistake, that was really a mistake.” [Laughs]

So now I think that I’m a lot more jealous of my time in the studio because it is about traveling there and making the time commitment to be there. There’s no less experimentation, I just experiment better because I have a little time to ruminate.

Darrow: How did you end up in Boston?

Locke: I went to Boston University in the ’80s. The whole bottom had fallen out of the economy, so it wasn’t like there were opportunities in Detroit. You bloom where you’re planted. I didn’t think about being an artist—I thought about making a living. It wasn’t until much later that I thought I would like to make art. I love New England. It’s such a hypnotically beautiful place.

My relationship to Boston was completely accidental, as was my becoming a teacher. I was in graduate school and as part of an internship program I taught a class, and I thought it was great. Like everyone does, I started hustling for adjunct jobs all over New England. I had a car and a subway pass and was teaching all over just to get the experience. It’s much harder now than it was when I was starting out. I see the way adjuncts are treated now and think “these poor people.”

So many people think education is a thing you do to get a job and not a preparation for citizenship or participation in a civic dialogue. I don’t have kids, but I want all children to be educated because educated children are less likely to murder gay people. It’s very simple. I have an investment in quality, public education because I believe that it’s a right.

Darrow: Thinking about your role as a mentor for this younger generation of artists, is there any advice that you try to give them?

Locke: I try to let them know that the “stupid artist” thing is over. Not being able to talk about your work or refusing to participate in any discourse is over. Some people are like: “oh, I don’t want to write an artist statement, or why should I have to talk about my work? My work should be evident and it should speak for itself. I’m a visual person”—all these cop-outs. It’s because they are undereducated and don’t understand the lineage they operate in.

Robert Morris and Motherwell were writers, they were theorists about art. Fairfield Porter talked about the importance of realism in the context of modernism. With Mira Schor and her journal M/E/A/N/I/N/G, you have all these women who are contextualizing their own practice. So the notion that somehow that’s the job of critics and artists just make stuff is asinine. Frankly, those people are just lazy.

I say to students all the time, “I really don’t care what you like. That’s not the discussion anymore. If it was just about taste, we’d be having a different discussion about art. I don’t like Picasso, but it’s not a question of liking him. The issue is his importance and his contribution.” So when we separate personal taste and these younger people—I sound like an old person, I do—young people have been so encouraged to talk about how they feel that they never talk about how they think. No one can argue with your feelings, so I don’t really care about your feelings. Truth be told, no one cares about your feelings. People do care about what you think though.

Darrow: You said in a talk that you’re not an emotional painter. I think that’s really nice. You’re thinking about what makes a good painting.

Locke: I don’t expect anyone to have the same emotional charge from my work that I have. People ask me what things are about, and I’m happy to talk about what I was thinking when I made it, but if it’s going to be remotely successful as an artwork it has to do something completely independent of me. I don’t believe for a second that what I think about my work is universal. I’ve never been that arrogant. People look and say, “this reminds me of so and so,” and I say, “oh, that’s great,” but that has nothing to do with me.

Darrow: One of the things I noticed in your paintings in the shows at Samson Projects and the Boston ICA is your use of the pedestal to display your paintings. It reminded me of Rauschenberg’s Combines. I wonder about not only the formal comparisons to his work but also your role as a gay artist and the history and context that brings to the conversation.

Locke: I think all that stuff is there. I’m a student of art history; am I going to do something original? That’s just crazy. There’s no such thing. The fetish for originality is a little nutty. I think that an artist tries to solve a problem and that an artist tries to make meaning, but those things aren’t necessarily the same activity. In solving the problem, a different kind of meaning was created.

Darrow: You use disembodied heads in a lot of your work, which pulls in other art historical traditions. Caravaggio’s Medusa comes to mind. Your portraits are very minimal compositions, just the head and a simplified background.

Locke: Medusa is such a great example because she is female sexuality, an icon of female power that reduces men to nothingness. She stiffens men who look at her—say no more.

Darrow: Your paintings use the tongue and characteristics that subvert the history of male portraiture. The tongue becomes a comical device, at times a phallic device, or a repulsive response.

Locke: The history of male depiction is about power. How do you make a man look vulnerable without making him look ridiculous? In my work, I’m much more interested in exploring that idea. What does desire look like, what does failure look like, what does excitement look like? What do those things look like? What do you look like when no one’s looking at you? The tongue was a way to talk about vulnerability—standing there with your tongue hanging out because you’re either lusting after somebody or you’re panting after a run. It’s this moment of sublime vulnerability that became really loaded for me. The tongue became its own character in the painting. That’s when things got really weird—I’d be in the studio thinking, “I can’t show this to anybody,” and that’s when you know you really have to show this to somebody.

Darrow: Let’s talk about your palette. You’re an excellent colorist. You use a lot of pastel and traditionally feminine colors.

Locke: It’s very French. In grad school someone asked why I was making these French paintings, and I remember saying, “I kinda like French painting.”

Darrow: You are from the “Paris of the West” [Detroit].

Locke: I did grow up with a Matisse painting down the street from my house. In art school everybody “gets” something. I got the color thing. I never really had to think about it. Growing up looking at the Matisses [at DIA], the Riveras in the courtyard, which are suffused with that sort of fresco light. And Islamic art, when I went to Turkey in 2008, looking at a grid of tile up against a Turkish rug. Color has always been exciting to me. I do think it’s traditionally French. I have to think about it as a female sort of thing, though. I don’t deny that. I was influenced a lot by Mira Schor’s book Wet: On Painting, Feminism, and Art Culture when I was in grad school, when she writes about getting lost in the sauce and then suddenly something gets resolved.

Darrow: Some of your works are explicitly erotic and others are just portraits. Do you juxtapose these works in shows?

Locke: The most sexual work I have made is Rapture, but I don’t find that work erotic at all. I think I find it incredibly sad. It’s about the elimination of a whole group of people because of the plague of AIDS. My mother had died, and I felt like I could finally make this work because she wouldn’t have to answer for it. It’s about when you’re a gay person, and you’re told that you’re the creation of Satan or an abomination, that you’re not welcome on earth and you’re going to be kicked out of heaven, and because of this thinking, healthcare is denied to you, and then all of sorts of people like you die. Some of you die in your apartments, some of you die on the streets, and your families who don’t want anything to do with you after your gone clean up your apartment and pauperize your partner. So that’s really what Rapture is about.

As for the erotic part of it, I was looking at a lot of pornography and was trying to make the drawings as matter-of-fact and sexless as possible, and in some ways I succeeded and in some ways I didn’t. I stand by the work; I think it’s one of the best things I’ve ever made. It’s probably the most outwardly political thing I’ve ever made. But having it in a show with my other paintings confused people. They couldn’t understand why those things were together. One is of the divine and one is of the perverse. Those things go together all the time, but because it’s about queer sexuality …

I’m in a show in the Bronx right now called “The Gay Show” with a painting called The Opportunists, which is based on a scene I saw when I was a kid in a department store. It’s of a guy sitting in a bathroom stall with a paper bag in between his legs, because there’s another guy standing in the paper bag. So from the outside it looks like a guy with a paper bag, but inside they are having sex in the bathroom stall, and I painted this beautiful pink and white tile behind them. It was the most exciting part of the painting! So here’s a scene of furtive and desperate sexual congress, and I’m painting the tile. That’s just the way my brain works.

Darrow: Who are some of your favorite artists working right now?

Locke: I love Anselm Kiefer. The way he bears witness in his work is exquisitely beautiful, the way he talks about things that no one else will. His recent show “Next Year in Jerusalem” was so powerful, even though a lot of people thought he was giving the Hitler salute. I thought, “yeah, he is, and he’s a German doing that.”

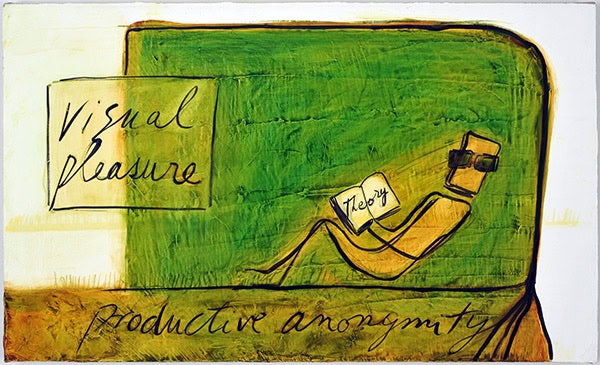

I’ve been looking at a lot of photography lately. Dawoud Bey is really exquisite, so smart, yet heartbreaking at the same time. His work is so much is about that lost possibility that that attack brought about. I’ve been looking a lot at Daniel Libeskind, at Maya Lin. I’ve also been looking at some recent Mira Schor paintings that she’s putting on her blog. Mira’s doing everything you’re not supposed to do in a painting, and they’re just awesome.

Rojas: She seems to be a recurring theme for you.

Locke: When I taught at SCAD, I made the students read her book. You can’t be a painter and not have read this text. There’s a whole bunch of texts: the James Elkins book What Painting Is, and Mira Schor again talking about the political import and the feminist practice of painting. I think that’s hugely important. So many people are making images and making paintings that are influenced by feminist practice and pretending that they’re not, and that’s hugely problematic for me. That book was gigantic for me.

Rojas: What is the role of an MFA in killing this notion of the stupid artist? Is it part of the solution or part of the problem?

Locke: It’s part of the problem. If you’re in a masters program, if your professors aren’t challenging you to talk and write and think about your work, you are being underserved by your education. And to be in a masters of fine art program and say “I’m a painter, so I can’t talk about sculpture,” someone has taken your money. I’m not saying everything has to be an interdisciplinary mishmash, I’m saying that disciplines have their importance. If you’re a painter, there’s this material called paint that you should develop some—I don’t know—mastery of. Being able to understand the poetics of painting is a lens through which you can understand the poetics of making art. And if you can understand those poetics then maybe you can infer other ideas about making to the other disciplines.

Rojas: Is part of the problem also that we’ve stopped pushing people to make value judgments?

Locke: We have dismissed the role of critical thinking in the practice of making art. This notion of “why do I have to take a contemporary theory class?” Because you’re a contemporary artist. Caravaggio’s great, but he’s dead. Titian’s great, but he’s dead. Titian is not expressing anything; he’s at work. He’s gotta paint some cherubs, he’s gotta paint some Jesuses, and then he’s gotta have lunch. He’s at work, he’s not expressing himself.

Darrow: You’ve displayed your paintings on pedestals and have cut into the walls of museums. Is that about trying to subvert the museum space?

Locke: It’s about trying to tell the truth about it. One painting was hung up against the donor’s name in the gallery. So, let’s not pretend that someone’s name isn’t on the space; this space exists because of that name. And that’s okay, but let’s talk about it. Or the fiction of a wall as solid and permanent—let’s cut a hole in it and render that fiction visible.

Rojas: What are you working on right now?

Locke: I’ve been thinking a lot about abandonment and loss, about the middle passage and people being thrown overboard or choosing to jump overboard. I’ve been thinking a lot about cotton and how that has affected every aspect of our lives. I live in New England, and Rhode Island was the site of one of the largest slave markets on the planet. That’s why Libeskind comes up so much for me, because of his memorial to the murdered Jews of Europe that has a huge presence in Berlin. Then I think about Rhode Island and how there is no evidence of what happened there.

Darrow: You have dealt with things around loss in your work. You have dealt with the loss of your mother.

Locke: Oh yeah, that’s just who I am. Orhan Pamuk said his main material is melancholy, so I think I’m sort of similar in that regard. I’m a gay man of a certain age; I survived a plague. In my Boston ICA show, there was a huge wall of heads, which [curator] Helen Molesworth said was like being at a cocktail party where everyone’s gone. That’s what life is like; you carry all these dead people around with you all the time. So that aspect of absence and presence, the presence of absence. I don’t think that’s going to go away.