Hugh O’Connor was murdered on September 20, 1967. The Canadian documentarian and journalist was in Letcher County, Kentucky at the time, gathering footage for a film he was making about the uneven realities of the country’s great myth: the American Dream. As he was standing on the porch of Hobart Ison’s home, pointing his camera at tenant Mason Elridge and his daughter, Ison pulled up to the house in his Buick and killed O’Connor with three fatal shots to the chest.

Elridge recalls this strange event decades later in the opening scenes of Elizabeth Barret’s documentary Stranger with a Camera (2000). A close-up shot frames his face as he looks down, away from the camera: “well, it had to be murder,” he hesitates, “it had to be.” Funded by several arts foundations and produced by Appalshop, Stranger with a Camera premiered at the 2000 Sundance Film Festival, where it was nominated for the Grand Jury Prize in Documentary Film. A cross between a personal video essay and an oral history, Stranger with a Camera tells the story of O’Connor’s murder through its complicated relationship to media politics in 1960s and ‘70s Appalachia. O’Connor’s death, the film proposes, is but one dramatic casualty of American mass media’s othering and victimization of Appalachian people and culture.

In the early- to mid-twentieth century, the terrain of Appalachian representation was vast and variegated. The hillbilly figure—virtually always white and poor, often primitive or outside of modern culture—appeared in comic strips, Hollywood movies, and television shows, and it informed popular representations of Appalachians. Documentary photographers and filmmakers took to Appalachia in the wake of President Lyndon B. Johnson’s war on poverty and his trip to eastern Kentucky in 1964. In the same year, an article entitled “The Valley of Poverty” accompanied twenty photographs of snowy landscapes and dirty-faced children by John Dominis in Life Magazine. Article author Michael Murphy described rural Kentuckians as “disease-ridden and unschooled” and claimed that due to the decline of the coal industry, they fabricated ailments for welfare money.[1] John Boorman’s 1972 film Deliverance famously depicted mountain dwellers as genetically degenerate and aimlessly violent, preying upon four urbanites on a camping trip. These are only a few notable instances in broader white America’s obsession with showing and seeing an Appalachia fundamentally alien to modern, metropolitan, civil society.

Such derogatory mainstream media narratives compelled Yale graduate Bill Richardson to move to Whitesburg, Kentucky, in 1969 to establish Appalshop, known then as the Community Film Workshop of Appalachia. An outcrop of a partnership between President Johnson’s Office of Economic Opportunity and the American Film Institute, the Community Film Workshop was originally tasked with training poor Appalachians in eastern Kentucky to work in the film and television industries. It quickly grew beyond its goal in scope and pedagogy and was defunded in 1971 due to increasing ideological conflict between Richardson and the Community Film Workshop Council (CFWC). Despite financial hardship, the break with the CFWC allowed Appalshop to fully transform from a technical training program for youth into a film and photography studio, a record label, and a roadside theater, all in one.

“Now we were the ones with cameras,” Barret proclaims in Stranger with a Camera, as the film shows behind-the-scenes footage of Appalshop filmmakers recording a fiddle player. Though Appalshop films were not monolithic in style or content, they broadly focused on Appalachians’ culture and agency. Some films did this by profiling culture bearers, including quilters, whiskey-makers, and herb doctors. More political documentaries centered on labor exploitation and miners’ unionizing efforts. Two films from the early 1980s, Elizabeth Barret’s Coalmining Women (1981) and Susan Baker’s Clinchco: Story of a Mining Town (1982), relied on sonic forms and media—music, storytelling, and voice, particular powers of the Appalshop audio-visual media collection—to represent Appalachian identity and the political culture of mining communities.

Through interviews with predominantly white female coal miners in Kentucky, Coalmining Women (1981) sheds light on histories of women’s exclusion from coal mining and their prominent roles in movement-building. Around minute fifteen, the voice of revered mountain feminist and sociologist Helen Matthews Lewis is heard, as she acknowledges the presence of female miners in early-nineteenth-century Great Britain, while a softly strummed string instrument hums in the background. Viewers do not see Helen Lewis speaking; instead, they see black-and-white figurative illustrations, like those in a textbook, of women underground carrying coal on their backs. Complete with informational illustrations, voice over, and background music, Coalmining Women draws from an educational video aesthetic reminiscent of PBS specials. The film thus ascribes to its subjects, all local stakeholders, an intellectuality often doubly denied to women and Appalachians alike.

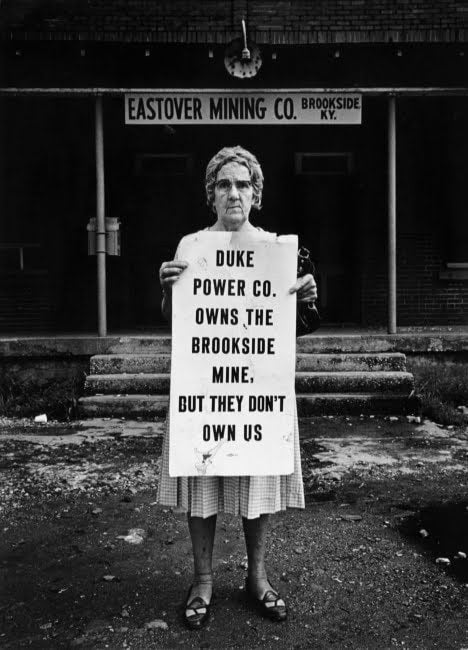

Shortly thereafter, as Helen Lewis describes women’s active roles in the United Mine Workers of America labor union and coalfield strikes, a photograph of Minnie Lunsford moves across the screen vertically. In the image, Lunsford, an elderly member of the Brookside Women’s Club, holds a sign that says “Duke Power Co. Owns the Brookside Mine, But They Don’t Own Us” during the 1973-1974 Brookside coal strike. “They [women] are often a militant component in the site,” Lewis says, as the image changes to a photograph of women coal miners behind jail cell bars. She calls them “an organizing and irritating force with which the authority and companies have to reckon.” While she speaks, the snaps of a banjo grow in volume. Then, West Virginia actress and singer Phyllis Boyens’ voice is heard covering Florence Reece’s well-known song “Which Side Are You On?” written during the 1931 Harlan County War, as footage of an exurban Appalachian landscape pans across the screen. The melody is both a telling example of Lewis’s lesson and a continuation of her story. In Coalmining Women, music and narrative, both replete with mountain accents, are contiguous; music reinforces the feminist politics of the short documentary.

In contrast to Barret’s short film, Susan Baker’s Clinchco: Story of a Mining Town (1982)[2] does not include raw footage or audio-visual interviews. Instead, it takes the form of a video photo montage—this seems fitting given that most of the photos came from, according to Appalshop filmmaker Herb E. Smith, photo albums from families in Clinchco.[3] The pairing of stagnant image and first-person voice over by locals is productive: It is as if we spectators are flipping through a photo album with older residents of Clinchco, who recount to us the racial and economic histories of a long forgotten, largely integrated American settlement built by and around a coal corporation and railroad company in the late nineteenth century. As documentaries on Black Appalachian or, Affrilachian, arts and cross-racial coal mining solidarity populate the media landscape today, Baker’s Clinchco serves as an understated, early testament to Black migration and labor in the mountain towns.[4]

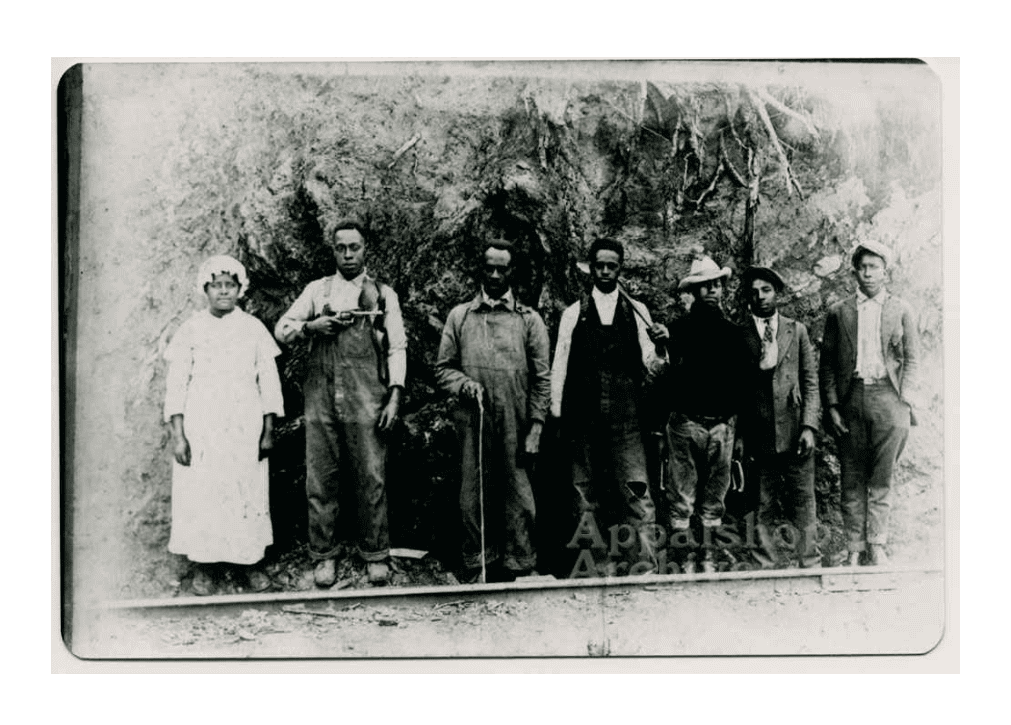

In Clinchco, the photograph occupies an ambiguous position between a reference to the speaker and a historical document of the young town. Around minute five, we see a photograph of a man sitting outside, and his voice discusses migration to Clinchco in its early days. Image and sound change simultaneously. A woman’s voice is paired with a full photograph of Black coal miners, as she recalls the death of a Black worker and the company’s disposal of his body. Before she finishes speaking, the film cuts to a photograph of an older white woman, potentially the speaker, sitting in a rocking chair and staring into the distance.

By pairing speaking voices with photographs of individuals, presumably Clinchco inhabitants, the film visually imagines the speaker, regardless of whether the photograph references the actual speaker. The effect is that the viewer registers the speaker as both Clinchco resident and expert: the speaker presents the town of Clinchco’s history, and she is also a part of that history. Without an interviewer posing questions, there is natural continuity between speakers and stories. This is what we might call a filmic-oral history.

What could be a photograph of a young, studious Dr. William Turner, a revered expert in Black Appalachian studies, accompanies a concise spoken account of the relationship between the abolition of slavery in 1865 and the migration of Black workers from northeast Alabama to southwest Virginia. As Dr. Turner recounts the transition of Black labor in the southern United States from slave labor to sharecropping to low wage labor, fuzzy photos of Black coal mining communities continue to flip. Unlike the photographs in Coalmining Women, these didn’t achieve fame. They’re intimate, quiet, unspectacular: they help us imagine everyday life in Clinchco, across time.

In Stranger with a Camera, as journalist Pat Gish of the Kentucky-based newspaper Mountain Eagle discusses the ethics of photographing poverty, she offers measured empathy for outsider media: “I don’t know what could have been done to show the problem [poverty]… You can talk about it, but it doesn’t really come through until you actually see it.” If mainstream media used film to show impoverished Appalachia’s backwardness, Appalshop media used film to resound Appalachian identity and politics. Coalmining Women dislodges music from its emotionally affective role on a film score or soundtrack, and instead affirms music’s narrative function. Music becomes the sonic embodiment of collective remembrance. Clinchco: Story of Mining Town draws from the tradition of oral history, building the sense of intimacy central to this kind of storytelling through its use of family photos. By the second half of the twentieth century, the broader United States had grown accustomed to seeing Appalachia. Hearing Appalachia, on the other hand—perhaps that was something new.

[1] Michael Murphy, “The Valley of Poverty,” Life 54 (no. 5), January 31, 1964: 54-65. https://books.google.com/books?id=_FMEAAAAMBAJ&printsec=frontcover&source=gbs_ge_summary_r&cad=0#v=onepage&q&f=false

[2] Watch Clinchco: Story of a Mining Town (1982) here: https://vimeo.com/205210592

[3] Herb E. Smith, “Appalshop and African Americans in Appalachia,” Appalachian Heritage 19, 4 (Fall 1991): 75-76.

[3] See: Media Working Group’s Coal Black Voices (2001) and PBS’ The Mine Wars (2016)

This essay is part of Burnaway’s yearlong series on Word of Mouth.

Find out more about the three themes guiding the magazine’s publishing activities for the remainder of 2021 here.