at McKinney Avenue Contemporary (MAC) in Dallas.

(Photo: courtesy S. Anker)

Atlanta artist Bojana Ginn recently visited with Suzanne Anker at the School of Visual Arts in New York, where Anker is the chair of sculpture. Ginn is particularly intrigued by Anker’s pioneering bio-art work, which she was familiar with from her own graduate studies, when she explored connections between art and bio-mathematics. Ginn graduated from medical school in 2001 in Belgrade, Serbia, and moved to the U.S. in 2002. She received her MFA from the Savannah College of Art and Design in Atlanta in 2013, and is now in the studio program at the Atlanta Contemporary Art Center. Her recent exhibition at Swan Coach House Gallery reflected her diverse background and interests.

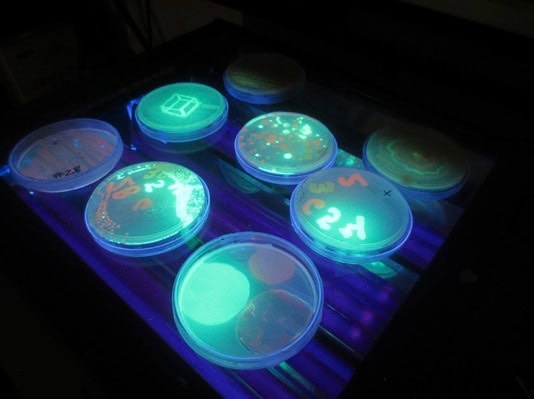

Anker and Ginn met at SVA’s Bio Art Lab, a cutting-edge, fully equipped laboratory founded and directed by Anker, where students can paint with bacteria, record creative processes under an electron microscope, and make 3D prints of their bio-sculptures.

Bojana Ginn: As a young woman, you had passion for both science and art. But you enrolled into an art school.

Suzanne Anker: Yes, I did.

BG: So, art won …

SA: Art won in a way by default, because I started out studying chemistry, which I loved very much. But when it came time to convert the matter into mathematical equations, it really became too picky for what I wanted to do, with the weights and measures and the equations with moles, for example, that was no longer feeding my desire to work with materials. So I switched out of chemistry into art where I could pursue a similar sense of wonder and investigation that was possible but, this time, in a much more subjective way.

BG: In the late ’60s you had an independent study with Ad Reinhardt.

SA: Yes, he was my teacher and it was pretty amazing to study with him since it was the first time I was exposed to art as a philosophical investigation. Before studying with him, my thoughts about art were much more about mimetic representation, decoration, aesthetics, and the sense of picture making. But after my experiences with him, it seemed as if art could refer to philosophical concepts, which really underscored my interest in science as well.

BG: Were your subjects always biological?

SA: Biological and geological, and now they are becoming a mix of the two. My interest in biology certainly has to do with the fact that biology is in a golden age right now, and the new imaging technologies and the investigations into genomes is unprecedented in the altering of life forms. But, at the same time, there have been investigations into new geographical areas, whether they are outer space or under the sea in very deep places, which has to do with theories about the origin of life. It goes back and forth between biology and geology at this point, since plants are being investigated in terms of their growing capabilities in anti-gravitational environments and many companies are also looking towards other planets as mining entities to get some minerals or metals that are in a very low abundance here on Earth. So, it is a combination of both.

BG: You exhibited at the Smithsonian in the ’70s. Was it unusual for an artist to exhibit at science institutions?

SA: I think at that point I was investigating paper as a material, and it was usually thought to be a surface on which to draw. But my investigations with paper had to do with its liquid capabilities and its ability to be reformatted into three dimensions. There were a number of other artists working that way as well, so there were many shows at that time about paper as medium.

BG: Who were the artists or other professionals that have influenced your work?

SA: I’ve always been an experimental artist. I still put together materials in new ways or begin to compound metaphors in new ways, and I think that a lot of my influence was not necessarily from persons but was from nature. Particularly the time I spent in Colorado in the Rocky Mountains—the amount of snowfall that was there, the way in which the sun hit the crystallized snow, as well as the freedom to be outside of a major art center and to be immersed in some bigger forces.

I’ve always also read a lot and that has influenced me greatly—most recently, the work of Margaret Atwood, who I think is really amazing in science fiction. Well, she doesn’t really call herself a science fiction writer; she considers herself a writer about scenarios which are possible because of things that have already happened. She considers herself a critical fiction writer, which is very different than just pure fantasy. I’ve also been greatly influenced by theory—Continental theory, French theory, the ways in which you can deconstruct image making and look at it as a form of knowledge production. I think this goes back to my early studies with Ad Reinhardt and the fact that a painting could refer to a philosophical concept or system, and I think that continues with me today.

BG: In the review of your exhibition “While Darkness Sleeps,” Charrisa Terranova states that your work is evidence that modernism never died. She says that you ask questions through scientific inquiry rather than postmodern irony. I would agree with that. I’m also one of those people who think that postmodernism is another form of modernism.

SA: I agree with that. Postmodernism is a late form of modernism, in which the fringes are now brought to the center. The idea of collapse, which we are undertaking right now, I think became evident. But the cynicism, coupled with the commercialization and entertainment industry, which essentially used media as a form of advertising, infiltrated the art world in the 1980s and essentially pointed to the lowest common denominator. So, the fact that postmodernism was a kind of melting together of styles outside of the historical domain as a way to create a mashup or a recombination that we find in every aspect of our lives right now, whether it’s genetic engineering, synthetic biology, newspapers, music, etc. You take what already exists and you reposition it.

As far as my work being within the realm of modernism or postmodernism, it is certainly not about irony. From time to time there is a little humor in it, but the negativity of irony doesn’t interest me. I think that the reviewer may have picked up on the fact that I have a strong aesthetic sense and that it is critical for me to use certain visual collisions to make people stop and think about what they are looking at. In that sense, I use beauty as a foil to the underlying dialectic that you can’t have life without death, etc. So this is a very old idea and it has the permutation of being reconfigured with the use of new technologies, which can offer up to the viewer visions that they have never been able to see. I thought that was a very good review… it was very thoughtful. I don’t consider myself a modernist, I consider myself a sort of systems thinker and someone who is interested in the criticality of the current practices, not only in art but in philosophy, psychology, sociology, geology. I find that art is a complex metaphor that touches upon all of these other things.

BG: How do you see the future of bio art?

SA: Bio art is ever expanding, and what is important about it is that it’s not material based—meaning, you can have painting, drawing, photography, performance, music, wet lab materials—and it is not geographically localized. So it is an international movement that I think begins to ask questions about altering life and the way in which new technologies change our lives.

BG: What are you working on now?

SA: I’ve been doing lots of traveling and exhibiting. I just came back from Austria and Berlin; I’m on my way to the University of Cambridge in the UK to be a discussant of a 25-member expert workshop on IVF. We will be looking at some of the issues involved with in-vitro fertilization, particularly because the first “test-tube baby” was made in Cambridge. It should be a very fascinating discussion. The piece I worked on in Berlin had to do with the petri dish as a cultural signifier. I had a table of 181 petri dishes that ranged from animal, vegetable, mineral, and configurations that were based on color. That, too, was an amazing concept because everyone knows what a petri dish is but no one knows who the father of bacteriology is … Well, there were a few; Robert Koch was very instrumental in finding out the microbes for tuberculosis, anthrax, and others. The petri dish was the vehicle through which these experiments could become sterile environments for discovery.