Is a seashell the loneliest object? An abandoned home of a squishy thing that left it in the lurch, either from outgrowing its narrow chambers or to rest in the belly of a larger animal, the seashell is a tender, brittle little container. It’s a container for many things: for a glowing inner softness; a pearl; a mollusk; a memory of a seaside vacation; a person’s dream of hearing something whooshing and ancient when holding it to the ear. Where will the seashells go when the beaches they wash up on have been gobbled up back into the ocean? Where will we?

Seashell empathy, along with turtle mourning, snake craft, and the joined voices of a dispersed minyan singing together comprise Sasha Wortzel’s solo exhibition at Oolite Arts where she was in residency in 2020. Dreams of Unknown Islands represents both a homecoming and a departure for the Florida-native who typically works in collaborative, time-based media and has been primarily based in New York for a decade and a half. Since 2017, Wortzel has been reacquainting herself with this landscape and the entangled scars of over development and colonialism that have thrown its future existence into the balance. This ecological catastrophe, along with the ancestral tools of Jewish ritual are the driving forces behind this new body of work which has been on view at the Miami-based art center since January 20th and closes this weekend.

Sasha and I spoke by phone about the project, her history, and her feature length documentary currently in the works on March 18. It has been edited for publication.

Erin Jane Nelson: Could you share a little bit about your background, growing up in South Florida and now returning to live and work in Miami?

Sasha Wortzel: I am from Southwest Florida, which is quite different than growing up on the east coast near Miami where it is much more developed and cosmopolitan. I grew up having a very strong connection to the landscape, to being in a fragile coastal environment living on a barrier island that is about half wildlife preserve. Sanibel Island is unusual because it’s one of the few places in that part of Florida that hasn’t been overdeveloped. It’s also known for seashells—it’s like one of the number one seashell places in the United States. So, growing up, I was required to take seashell studies and to become a junior naturalist. That definitely shaped a lot of my relationship to place in the work that I’m doing now. But it’s also a very precarious environment that I’ve watched really change just over the course of my lifetime.

I left and moved to New York in 2005, and I have since called New York home and still do in many ways. But in 2017, I came down to do a residency in the Everglades National Park with the idea that I wanted to make a film about the history of the everglades to try to unpack why we’re experiencing so much ecological collapse right now. That residency was really transformative for me. I felt that I didn’t want to be traveling back and forth to make this project; I wanted to move home to be more embedded in the place that the work was going to be an offering to. So, after I raised some grant money, I relocated in 2019. And I’ve been here since.

EJN: That sense of being embedded in a place, in a community feels so much a part of how you’ve approached all of your projects. Not just traveling to a place, but really just immersing yourself so much in and among a history or a space. Your work has largely involved intense and prolonged collaboration with other artists or subjects. With this solo exhibition, have you felt like it has been challenging to move away from collaborative projects? Could you share a bit about how the process of collaboration has come about in your previous works?

SW: The collaborations I’ve done often happen through my relationships and community and finding common ground to have a creative exchange with somebody. In general, I am really interested in the ways we are inextricably entangled with one another, and with dominant power structures that regulate our lives. I’m interested in this idea of being part of a network tangled with others and bringing other people into a creative process together. In a conversation with the curator of the show Kristan Kennedy, she said, “You know a lot of times collaboration is about erasure of authorship, but instead your approach to collaboration is additive and about naming authorship.” And I thought that was a really nice way of putting it. It’s all about bringing together a group of people to carry out something. That’s also a lot like the way that social movements or community organizing happens—solidarity and collusion in service of something larger.

I think that this project does depart in some ways from that process, which is a little scary and vulnerable for me. But I also approached it very much in the way that I often work on a film project: I brought together a team of people deeply rooted in South Florida to help me carry out this vision. I worked with a really talented, sound designer and sound engineer to realize the seven-channel sound installation, a leather artist on the stitching for my chairs, and my partner on cinematography for the videos. And then there’s also the way the sound piece is additive too. I invited people in my life to recite the Mourner’s Kaddish, to say that prayer and make their own mourning ritual with it and then to send those recordings back to me. So even though we weren’t able to gather, and I was sitting alone in my studio, I was working with my community, weaving together the energetic residue of their performances, to make this collective piece. I was interested in Jewish rituals around death and grieving and bereavement because they demonstrate that mourning is a communal process.

EJN: I’m curious how—as an artist who’s explored issues of queerness, representation, and advocacy—you’ve been able to square your political ideology and identity with the traditional Jewish norms around gender and power?

SW: My approach has been to take what I need, and cast out the rest. I’ve been really inspired by a lot of the Jews that I know who are queer, trans, and non-binary and are making their own rituals through that lens. And I think there’s also so much in Judaism that has been filtered out because of patriarchy and misogyny and binary notions of gender. I’ve been inspired by the work of Dori Midnight, an intuitive healer who works with plant medicine and has been exploring Jewish practice and reclaiming it through a feminist and queer lens. For a long time, I was turned off by a lot of those traditional values and felt alienated from what I understood Judaism to be. It’s only through my relationships and through the work that other people are doing that I’ve started to find my way.

The way I began thinking about Kaddish is pretty obvious. The projects that I’ve been working on in Florida Everglades arose out of grappling with being from a place that may cease to exist, a place that is most likely going to look radically different in our life. I was looking for rituals that I’ve inherited from my ancestors that I could take up and make my own. Then, of course, the pandemic began early on in the process of developing the show. And so, the Kaddish and sitting Shiva and mourning took on a heavier weight.

EJN: This exhibition also feels like a departure from your past work because you are making objects in addition to video work. Can you talk a little bit about how sculpture came into play?

SW: Most of my artistic career, I have predominantly worked in video because I was drawn to the kind of storytelling and intervention that it facilitates. It was also tactical, because I could work around having a full-time job and less access to a studio space. I could take vacation time, shoot a film, and then edit nights and weekends.

Coming to Florida, however, also came with the intention that I wanted to start to experiment more with object-making. A film can be shared in the cinematic space. I think it’s so important for us to collectively sit in the dark and watch cinema—that does something really special that I’m desperately missing. While my work often is rooted in moving image, I’m also interested in what happens when you take that energy and transfer it into a physical space through sculptural elements, sound, or performance. What happens when the viewer is engaged in a cinematic world beyond the screen?

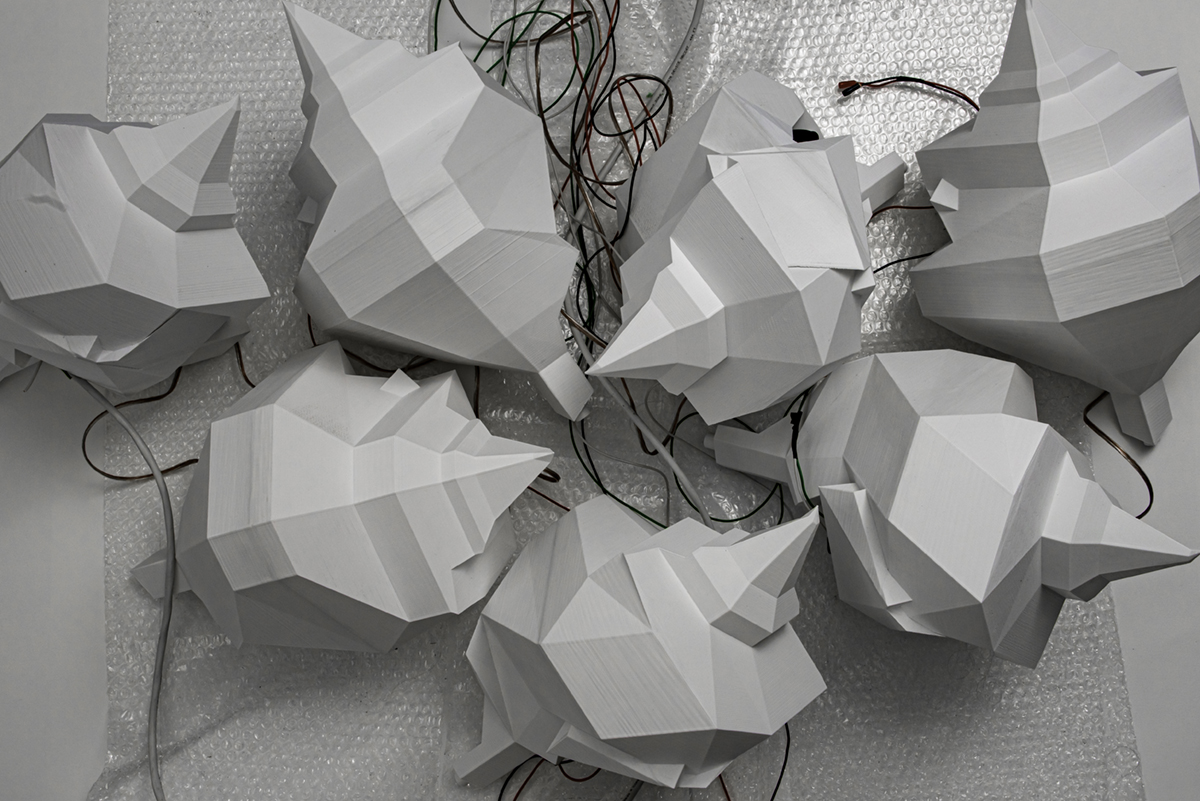

One of the first things I was interested in making were these shell-like sculptures that would play with the form of the horse conch, the state shell of Florida. When I first moved back, I took a walk on the beach during hurricane season, and I found this gorgeous, sponge-eaten horse conch which made me think about the folk myth of hearing the ocean by putting a shell to your ear. Seashells act as amplifiers—you are actually hearing the ambient sounds of the world around you and of your own body. I was interested in that slipperiness between one’s body and the ocean—between us and other forms of non-human life. So, I created these 3D printed shells that have all these weirded, almost unnatural angles and edges that amplify difference. I was thinking about the impermanence of things, so I wanted to work with things that still have an ephemeral quality. I printed the seashells with a material that will biodegrade.

The chairs that I created are used chairs off Craigslist reupholstered in skin from snakes that were removed from the Everglades, because they are considered an invasive species, and would have been thrown away.

I was interested in Jewish rituals around death and grieving and bereavement because they demonstrate that mourning is a communal process.

EJN: Could you share a little bit about the Everglades film that you’ve been working on?

SW: River of Grass is a feature length documentary that takes audiences on a journey through the past, present and future of the Florida everglades. The film re-imagines Marjory Stoneman Douglas’ The Everglades: River of Grass, which came out in 1947 and was one of the first books that chronicles both the environmental and cultural history of the Everglades. In many ways it tells the story of the origins of the United States, about how colonization at its historical roots explains why we are experiencing ecological collapse, rising sea levels, toxic algae blooms, pollution, displacement, dispossession. In the film, Douglas is a spectral narrator, she guides us through the landscape, through these interdependent ecosystems and the communities living along the watershed.

Passages from the book about the past, are placed in conversation with present-day stories at the same coordinates. Ultimately, a lot of the work that I’ve been making considers how the past is haunting and shaping the present today. I’m aiming for it to be finished sometime in 2022.

EJN: In my mind, documentary projects have been the primary vehicle of making media about climate change—bearing witness to something, trying to be empathetic, showing people the reality of it. Obviously that strategy hasn’t worked, and so it seems like your documentary is taking that form and then sort of transmuting, warping it into something new. What are your thoughts on documentary practice and the ways it maybe fails in precipitating the response to climate change that filmmakers wish they would?

SW: In environmental storytelling, climate crisis is often isolated from larger socio-political structures and systems of injustice. I’m interested in approaching the documentary not in an information-driven way, but as a deeply imaginative approach to these issues—looking at how climate entangles with many other systemic issues including indigenous sovereignty, racial and economic justice, and immigration. In her book, Douglas describes the Everglades as “they”. She uses a gender-neutral pronoun that inherently binds the Everglades to this idea of the collective, the non-binary, that evokes notions of kinship. I’m interested in the way a documentary can approach this kinship between people, animals, plants, water, land, and the dead.

The other thing about documentaries—this also happens a lot around funding— is this idea that they must have a very specific message and an impact campaign, a use value. What is the actual measurable impact of the film and, how is it going to provide solutions? I am very interested in how docs can forward social movements and ongoing grassroots organizing, but I’m not interested in making one that has one very clear solution because I don’t claim to know what that is. I want to pose questions and open up space for there to be conversations that center and amplify the experiences of communities that are being most impacted by the climate emergency so that we can collectively imagine new ways forward together.

Dreams of Unknown Islands: Sasha Wortzel is on view through April 4th, 2021.