Idea collective John Q stopped by my apartment for an interview in August, and we chatted about the Atlanta art scene, the art of remembering, and the current work they have up at the Zuckerman Museum of Art. I knew member Joey Orr from my days working as a gallery assistant at the Atlanta Contemporary Art Center and Andy Ditzler was a familiar face from attending Film Love, the film screening series that he curates. This was my first time meeting the witty Wesley Chenault, and I enjoyed learning more about his work. I couldn’t help but wish that the trio always be in the same room together—playing off of each other’s conversation and finishing one another’s sentences. But, with Ditzler in Atlanta, Chenault in Richmond, Virginia, and Orr preparing to move to Memphis—I came to the conclusion that John Q’s work is the common thread that will keep the three artists linked together across state lines.

Sherri Caudell: Joey, why are you leaving Atlanta?

Joey Orr: I’ll be taking on the position of visiting assistant professor of contemporary art history at the University of Memphis. I’ve never been to Memphis in my life. I think it’s an awesome place to go play for a little while.

SC: What will you miss and not miss about Atlanta?

JO: What I’m not going to miss is being a graduate student and an adjunct professor. I love being a professor; it’s the adjunct part I don’t like. I’m going to miss a lot of things about Atlanta. This is a city that I’ve been in most of my life. So I have friends and family with very deep connections here. Atlanta actually feels like a small town to me— every time I go out I see people I know, and that’s something that takes a long time to cultivate in other places.

SC: And Wesley, you live in Richmond, Virginia, and Andy is based in Atlanta?

Wesley Chenault: Yes, but I lived in Atlanta for almost 20 years.

SC: What are some of your favorite “off the map” spots in Atlanta?

WC: One of my favorite things about Atlanta are the areas that have kind of been neglected. I used to live in Candler Park, and when you walk around Freedom Parkway, there’s a lot of concrete steps that just end because the homes were demolished in the ’70s to build an interstate. So they just tore down that whole swath of land, but what remains is like a palimpsest. And I love Atlanta because it is a palimpsest. It’s like an archeological dig. To me, those are the most important and interesting places because that evidence will be gone soon enough.

SC: Joey, you did a piece, Info/Burn, at Sumptuary at MINT Gallery a little while ago. What did that work focus on?

JO: It was about how access to new scholarship is regulated. I think a lot of people don’t really understand this, but most new scholarship that’s produced is contained in institutional subscriptions that you don’t have access to. It’s maddening. Set knowledge free! I have access to several databases through different colleges and universities, and so there were pads that you could write a research request, and I would do the research for you. It’s not legal for me to give you that information because you might use it in a proprietary way. So I would make notes on the research and then I would burn it. I started an archive of ashes of the information that was not allowed to circulate. I was doing serious intellectual labor and it wasn’t going anywhere. In some ways, it was freeing to do it because I didn’t have to worry about how to deliver it or how to structure it. I was simply at everyone’s disposal, but no one was getting the results of my work. It was very satisfying for me personally. I was actually performing research for people. You literally walked in and watched me research.

SC: How so you consider your work a kind of public scholarship?

Andy Ditzler: We like to take the process of scholarship, which is research, and the asking of questions, and archival materials, and enact that process in public. We did an event at the Atlanta Contemporary Art Center where a collaborator in San Francisco sent us a box of archival materials and we opened it as part of the event and went through it. It’s scholarship where the results have an application publically, but also the process of scholarship is exposed.

SC: So you’re opening up the process to a wider audience. At the “Hearsay” exhibition at Zuckerman Museum [through October 25], you guys are exhibiting work called Take Me With You, along with a catalogue. Tell me more about the installation that’s on view.

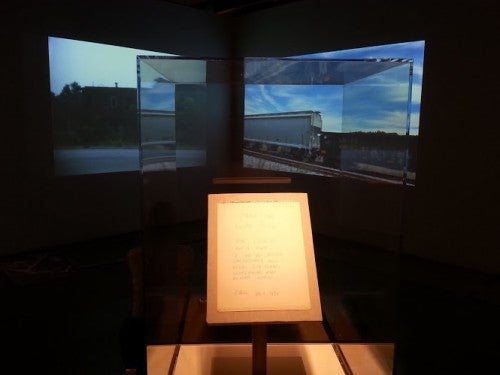

JO: It’s a two-channel video installation and a recreation of an archival object. The Campaign for Atlanta that we did at the Cyclorama was something we called a performative essay. We felt that it was an institutional intervention and a way for us to perform the research that we were conducting about queer migration. So, after that was over, we got an opportunity to turn the performative essay into an actual essay, which was just published in June in QED, a journal out of Michigan State University. We turned it into a written form. Take Me With You is the same work in a purely visual form.

AD: When you drag the work through different forms, different questions and results come up. Things that got dropped from the Cyclorama piece came out more in the written essay in QED. For example, early cinema and how train films do a certain thing with motion. And then suddenly you’ve got photographer Crawford Barton behind the wheel. And so the train film becomes the road movie and the road movie becomes the home movie. For Take Me With You, we took a different tack, which was that they’re migrating and we think they were driving from Atlanta to San Francisco. He’s from Resaca in North Georgia. So Joey and I said, let’s retrace this trip backwards. Let’s drive from Resaca instead of to San Francisco and let’s videotape it. So we’re kind of passing him on I-75 but 40 years later. When we intercut our road trip in 2013 with Crawford’s, we got to talk about motion, time, and what it’s like to be Crawford’s children, in a sense. Crawford was part of the first-wave of gay liberation in the ’70s, and we are in some sense the future that he was imagining.

SC: So you’re recreating this parallel history, but it’s a future history.

WC: It’s a future history—a capturing of that desire for a relationship with the past and the future. The work at Zuckerman is more explicit and goes in a more minimalist direction.

AD: Where the Cyclorama was about migration and a desire for the future, this piece is about our desire to connect with the past. Time is how you measure a film, but it’s also time in the sense of historical time, because we’re looking back 40 years. So we have chronological time, we have historical time, we have the time of the driving, and the time of the video.

WC: The catalogue has two scholarly essays and an interview with public historian Julia Brock. In Shawn Michelle Smith’s essay, she draws out the idea of queer temporalities, which she sees in our work. You get these three perspectives in the catalogue—you have Jonathan David Katz, who is an art historian, Shawn Michelle Smith, who is more visual studies, and Julia Brock, who’s public history—but public history is very much interested in artistic practices and where these things might come together.

SC: How does the aspect of storytelling enter into your work?

JO: When you say storytelling, it makes me think of oral tradition as opposed to written history. And I think that resonates with us a lot because we’re much less interested in historical narrative than we are in how memory gets replayed differently each time we do the remembering.

WC: With Memory Flash, we had the executive director of Eyedrum Art and Music Gallery, Priscilla Smith, who was reciting the script in toto, but then there were people planted in the crowd who were kind of echoing and reading parts of it.

SC: How does being queer inform your work? Is it a political aspect for you guys?

JO: Our work is about memory that uses a queer context, but on the other hand I’m less interested in the idea of queer as an identification category and more interested in queer as a set of possibilities, as a strategy for disruption.

AD: Because generations before us have fought in certain ways, including making an identity. We have the luxury of saying, maybe I don’t want to be that identity so much now, and maybe I want to use the “queer” as a set of practices. This points to something other than the politics of sexuality.

SC: How do you guys function as a collective? Have you reached a harmony with the different ideas each of you brings to the group?

JO: I have had a great experience working with these guys. I’ve noticed in our process, when we work on things, we talk forever about what we’re going to do, we share research, and we share ideas. Then we decide that this is the concept, this is what we’re going to execute, and then at that point I always feel like all three of us are thinking the same thing and we’ve agreed and we’re going to do the thing that I see in my head.

AD: There’s always some aspect of whatever we’re presenting that we are all in agreement on, then it turns out that we’re each coming at it from a different angle. I think you need both for collaboration. It’s been really rewarding in that way.

WC: I wonder sometimes if we weren’t all interdisciplinary what it would be like, because interdisciplinary work forces you to be actively listening. The logistics work is always interesting because, I think, Andy has gained practical knowledge through curating Film Love by himself. How do you take it from that fun, awesome dream and then manifest it? There’s a respect for communication. I think these guys are very generous with their time and their willingness to be open to listening and seeing things. And this is the only collective I’ve worked in, and it’s been very changing for me. It’s pushed my own thinking in a very productive way, and I think that’s what you hope for in any practice—is that you evolve, you change, you respond.

JO: It makes me increasingly dissatisfied with very traditional sit-alone-at-your-desk work. I want to underscore a word that Wesley brought up, which is generosity. I’ve never been in a collective like this before either. If Wesley has a feeling that a project is going in a direction that he doesn’t like so much, that can be said, and no one’s feelings are hurt because we’re all actually trying to do the same thing. That we can all be honest and all support each— that makes a huge difference.

SC: Wesley, what other projects are you currently working on?

WC: I’m actually revising a manuscript for publication. It’s my dissertation that I’m revising so it will be about gay and lesbian Atlanta 1940-1970. It is interesting, going from work that’s collaborative to work that has me sitting by myself. But, there are parts that are deeply satisfying, like when you’re at that point of discovery in research where you recognize that you are connecting things and you’re onto something. But then you can get trapped in your head, and with the collaborative you’re always talking.

SC: What is the collective’s relationship to the South and Atlanta in particular?

JO: We’ve mined a lot of our content from Atlanta’s past. The resource material for all of the Memory Flash work mostly came from the collections that Wesley was working on at the Atlanta History Center. All the work about migration was looking at which cities become destinations for queer migration, and Atlanta has been one of those.

WC: We have kind of exploited our knowledge of this place, but also I think our desire is for something that we can’t quite grasp. I think our work resonates with the South in the way in which you can’t talk about the past and not address the particularities of racism and civil rights, and all these things that happened here.

SC: How does your work as an idea collective relate to Situationist theory?

JO: One of the things behind Situationist theory is that if I am a different race or class than you, we’re probably not going to cross paths because the things that you’re required to do in the city only lets you see certain parts of the city. So one of their strategies would be to use a map of Paris in Berlin to find your way, so that you end up crossing barriers that you wouldn’t think to cross. So the idea about Situationist theory in terms of Memory Flash was the fact that we were on the street and as people would pass, we would disrupt their normal activity.

SC: Do you guys feel like you are somewhat on the fringes of the Atlanta arts scene?

JO: I think every artist working in Atlanta is on the fringe of the Atlanta arts scene. We don’t actually refer to ourselves as a collective but as an idea collective. And the reason for that is because we feel that sometimes what we do looks and feels like art and sometimes it looks and feels more like scholarship, or public scholarship. I’m not concerned with the way the work gets categorized. We work across disciplines and we work across formats. I can imagine a way in which some people would classify our work as visual art and some might classify it differently.

SC: What would you change about the Atlanta arts scene?

WC: Since I left there have been changes. I left around the time that the Atlanta Journal- Constitution stopped running arts coverage, and BURNAWAY filled that void and was just getting its feet. It seems like there’s been more work to draw a spotlight on Atlanta. There are new organizations like the Goat Farm. I’m in Richmond hearing about things in Atlanta that I think are interesting changes.

JO: Anyone who has spent time in more than one city will tell you that every city has really awesome things about it and really challenging things. It’s possible to get things done in Atlanta that you could not do in other cities. I think that’s an amazing strength that Atlanta has. There is no sense in Atlanta wanting to be something else, why would it want to be?

SC: I came back to Atlanta after spending 11 years in New York City and was able to start a reading and performance series for women here. I never would have been able to do that in New York because they already have a million reading series. So you can actually make some sort of mark here.

JO: One thing that can be a challenge with the Atlanta arts scene is that it’s so small and generally so supportive of everyone that we lose a level of criticality, because everyone is cheering for everyone.

SC: Joey, in September you’ll be curating an exhibition of works at the Atlanta Contemporary Art Center. Can you talk about some of your curatorial ideas behind the exhibition and how you selected the artists?

JO: The parameters that I was given by the ACAC was that I needed to deliver an exhibition that used people who had participated in their studio program over the past 10 years. They were also explicit that it was going to open during Art Party. It’s unwise to curate against your context, so I just needed to accept that it was for a party and curate for a party. There are seven good walls in the galleries at the Contemporary right now, and I have assigned three artists per wall and I’m asking for exquisite corpses on the walls. One of them is a video exquisite corpse. The title of the show is “Exquisite Exhibit: Parlour Games from the Studio Artist Program” [September 13-October 11].

It had been almost 10 years since I’d done studio visits in Atlanta, and I did about a month’s worth of them and it was amazing. Some of it was like a family reunion; some of it was getting introduced to the work of people that I should have been introduced to so many years ago. It was great to talk to other artists in their studios, and people were very forthcoming with me. They were telling me where they were in their process and what their challenges were here. Apparently, it’s common that artists feel like there’s a dearth of exhibition opportunities here in the city. Which is interesting from my perspective, because John Q couldn’t do more than we do. But, I heard that from a vast majority of the people that I visited.

SC: Andy, what have you been working on outside of the John Q projects?

AD: I’m a doctoral student at Emory, writing a dissertation on the subject of curation and film. This grew out of Film Love, which I’ve been presenting since 2003. Film Love is a series of screenings of rare films, but it’s also a way to think about curation as a process, through the moving image. We’ve incorporated cinema into many John Q projects, and in turn John Q has influenced my thinking about what curation does. For example, I’m currently exploring the idea of the unseen in cinema, with events that highlight disappearance and absence of film in addition to the projection of film. This is one way in which John Q’s approach of using ideas from queer theory and history to explore things outside of queer identity has been fruitful for me. As a composer and musician, I’m also eager to see how ideas like these translate into musical forms and performance.

SC: What’s next for John Q?

WC: We’re taking a breather, but we’ve got some ideas circulating about what we will do next and whatever we do is probably going to pick up the dynamic of us being dispersed. I want us to do something in Richmond. The art scene there is amazing—they’re building the ICA and there’s the School of Arts at Virginia Commonwealth University. It’s a city that has kept a lot of its past—good, bad, and otherwise.

SC: What is your relationship to Atlanta’s queer community and have you gotten a response from that community based on your artistic endeavors?

WC: The press has been exceptionally supportive about circulating information and trying to draw attention to the work. Shortly after Memory Flash” we went to Eyedrum and someone had painted this big mural of a gay family tree and on it was the Jolly 12, one of the pieces from Memory Flash, so it’s interesting that it got picked up so quickly. At the same time, you have faculty at Emory University making references to John Q’s work in their syllabi. We did a piece at Outwrite bookstore, which is no more, but there’s been great support and interest in the work.

JO: Memory Flash was based on the concept of the memory palace. And the memory palace is this mnemonic device that’s originally part of the ancient art of rhetoric. It addresses how you are going to be able to remember huge chunks of text. We were thinking about making the city of Atlanta a kind of memory palace. We would take memories from these queer oral histories that nobody knew and create situations where people would remember them. So anytime they drive through Atlanta, when they pass this one spot, they’re like, “the Jolly 12.”

SC: Would you categorize your work as site-specific?

JO: The context is always very important. We had the show at MOCA GA, but that took place in their Education and Resource Center, where their archives and collections are kept. We very specifically wanted that space because it spoke to our interest. This show at the Zuckerman is the first time that we’ve ever shown in a strictly fine art context.

WC: When we did the Southern Constellations Residency at Elsewhere in Greensboro, North Carolina—that was site specific. We chose to work with their library.

JO: The “Hearsay” exhibition is moving away from a lot of the work we usually do, which is rather ephemeral and performative. We can go to the museum and see our piece—it’s a thing in the world, which can be shown somewhere else. Our work isn’t usually like that—so it’s nice.

Sherri Caudell is a poet and writer from Atlanta.