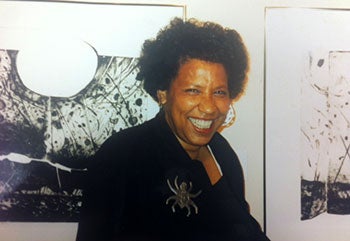

“Creating Matter: The Prints of Mildred Thompson,” at the Michael C. Carlos Museum at Emory University through May 17, offers a rare and focused glimpse of a prolific yet under-recognized artist who defied norms and refused to be categorized, instead choosing a lifelong exploration of abstraction for its ability to convey universal themes.

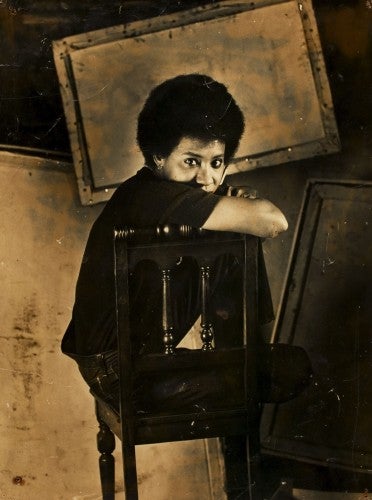

Thompson was an influential figure on the Atlanta art scene as an educator and exhibiting artist, teaching at Spelman, Agnes Scott, and the Atlanta College of Art, and working as associate editor at Art Papers. She lived in Atlanta from 1986 until her death in 2003. A native of Jacksonville, Florida, Thompson spent much of her adult life in Europe, where many African American artists found more acceptance and success than they did in the white art establishment in the U.S. Thompson moved to Germany shortly after graduating from Howard University in Washington, D.C., spending three years at the Art Academy of Hamburg. In 1961, she moved to New York with the anticipation of starting her art career but, discouraged and discriminated against, returned to Germany two years later. Following a more successful sojourn to the U.S. in 1975, she spent five years in Paris before moving to Atlanta in 1986.

Prior to the opening of “Creating Matter: The Prints of Mildred Thompson” at the Michael C. Carlos Museum at Emory University [through May 17], Savannah-based independent curator Melissa Messina, who is curator of the Mildred Thompson Estate, chatted with Andi McKenzie, associate curator of Works on Paper at Michael C. Carlos Museum, about the impetus for the exhibition, Thompson’s unique imagery, and how printmaking factored into her expansive creative practice.

Melissa Messina: What is your background and curatorial interest in works on paper?

Andi McKenzie: This is my third year with the Works on Paper collection at the Carlos, and I count myself as one of the lucky art students who landed a dream job. My undergraduate degree from Berry College is in studio art, specifically painting. After a brief stint in graphic design, I enrolled in the art history MA program at the University of South Florida. In Tampa, I got my first taste of curatorial work and never turned back. I’m currently a PhD candidate in the art history department at Emory, focusing on the intersection of Catholicism and indigenous spirituality in Latin American art, and printmaking in early modern Germany and the Low Countries—pretty far afield from contemporary art. The beauty of curating works on paper, though, is that the artworks span centuries. I work with everything from medieval manuscripts to Renaissance drawings and prints to contemporary works of art and photography.

MM: How did you come to know Thompson’s work? How did this project develop?

AM: Two years ago, I visited LaGrange to see the Cochran Collection of works on paper. Wes and Missy Cochran were incredibly gracious hosts, and gave me a tour of their home and their lovely gallery. I was blown away by the breadth of their holdings, particularly of African American artists, and began to think of how we could highlight this amazing collection at the Carlos. It was about an hour into this first visit that Wes pulled out Mildred Thompson’s “Mystery” series of etchings.

MM: What about the work spoke to you?

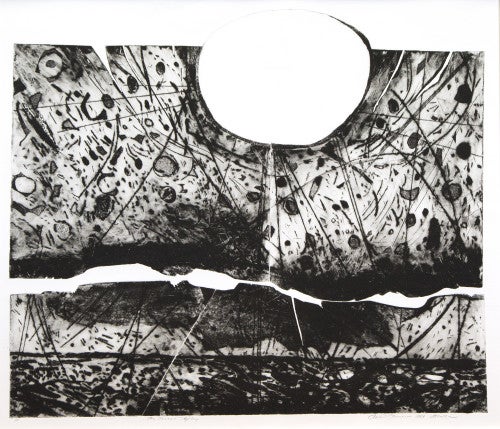

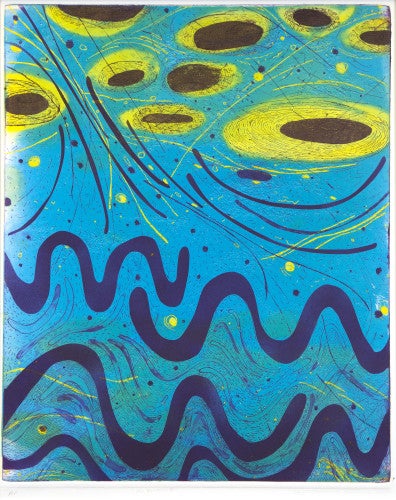

AM: I was completely arrested by her work. Her prints crackle with energy. Even the blank, white spaces in her graphic work contain life and movement. In true art student fashion, I stood with my nose practically pressed against the glass trying to figure out her process. How was the paper so sculptural? Did she use multiple copperplates? Did she cut a single plate and fit it back together? I’ve heard it on good authority that she ripped plates to create the printed texture, though I still don’t know how that’s possible. She was barely five feet tall! But as I’ve learned more about Thompson from her friends, admirers, students, and collectors, it seems like she could create anything—drawings, paintings, prints, sculpture, photography, music. If she decided to do something, it was done.

MM: Tell me a bit about the show and its focus.

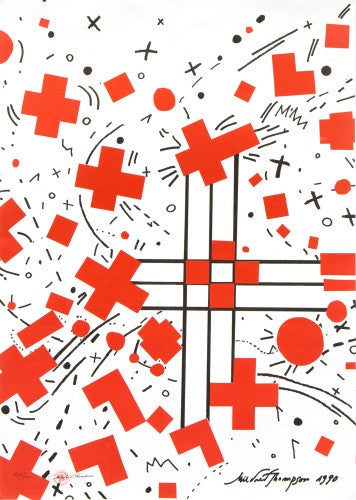

AM: There are 17 prints in the exhibition. Thompson’s work needs room to breathe, so overloading the space was not an option. The exhibition coincides with Emory’s Year of Creation, with the primary theme being Thompson’s exploration of the cosmos, scientific theory, and the most elemental parts of matter. It is organized loosely chronologically, and focuses on her mature work. However, I wanted also to emphasize her enduring ties with Germany, so I included one early etching alongside a poster that the German Red Cross commissioned in 1990.

MM: Thompson dedicated the better part of her life to championing abstraction for its ability to express universal themes. As a professor at the Atlanta College of Art in the 1990s, she gave brilliant lectures about abstraction and taught its expressive principles – now the stuff of art school legend. Students, including myself, flocked to study with her. So I was surprised when I recently discovered her early figurative works, pre-1970s. Will you be including any figurative works in the show?

AM: How I wish that I could have taken one of her courses! As an aside, it is so evident that she was a brilliant teacher. Her work, almost without fail, compels the viewer to become a student.

To answer your question, yes, there will be an early work in the exhibition. The Carlos was recently given a small, figurative etching from 1959. I included it for two reasons: to emphasize her transition from the figurative to the abstract, and to demonstrate that, even in her early figurative work, she was already exploring the texture variation and the repetitive, often symbolic, forms that appear in her later work.

MM: Thompson often used the term “multiple originals” when referring to her prints. They were certainly—and intentionally—experimental, even from the beginning of her artistic practice as a graduate student in Hamburg. Very few in a series ever look exactly the same. The Museum of Modern Art and the Brooklyn Museum, for example, own the same print and there are differences in each even though they are part of the same edition. This is rare for a printmaker, no? Can you speak to this explorative aspect of her print process?

AM: Are differences within editions rare? Yes and no. It is common, especially during the early years of printmaking, to see differences in printed quality between an early run impression and a late run impression. But these differences are rarely the intention of the artist; rather, they result from changes to the plate due to use, different inking practices between printers, etc. Intentional changes generally result in new printed editions that are reissued as second state, third state, and so on (or are posthumously designated as such by historians). But you are right, artists rarely make changes within an edition, especially when the editions are small in number. Historically, the most well-known exception to this rule is probably Rembrandt. He consistently explored new methods for achieving light and dark in his etchings by varying plate tone. Essentially, plate tone is created when the artist leaves ink on the surface of the plate. Rembrandt often left tone on the plate, pulled an impression, then wiped away ink or added more, pulled another impression, and so forth. The resulting prints can vary greatly in mood.

Thompson manipulates plate tone in much the same way. For example, she left the top portion of plate 4 in her “Death & Orgasm” series completely un-inked, creating a sense of stillness and quietude in the print. In contrast, the plate tone and stray marks that remain in the upper section of the fifth plate in the series enhance the movement already present in the forms of the final print. Thompson’s explorative methods in printmaking allowed her to push her concept in several directions at once, and I think that is one of the reasons that she was so committed to the medium.

MM: Thompson’s mature work is non-representational, forgoing any narrative or autobiographical reference. She instead chose to interpret themes relating to sound, music, and scientific theory and phenomena. Are there any particular works in the show which present these themes that stand out to you?

AM: Absolutely. The exhibition includes several prints, made at Caversham Press in South Africa, that demonstrate Thompson’s interest in scientific theory and sound. They relate visually to a number of “String Theory” paintings that she created here in Atlanta. Her fascination with the creation of the universe and visualizing the unseen, down to the smallest parts of matter, inspired the title of the exhibition.

MM: I know you were also interested in including one of the vitreographs she made at the (now defunct) Littleton Studios in North Carolina in the mid-1990s. Why were these of particular interest?

AM: Vitreography is an unusual and sometimes arduous printmaking process using glass. An image is fixed into or onto a glass matrix (rather than traditional copper, wood, or stone) so that an edition can be printed. Images can be painted, engraved, etched or stippled into the glass, and I suspect that Thompson used multiple methods, probably painting and etching.

MM: Thompson is probably better known as a painter, but printmaking factored prominently into her practice, as early as graduate school in the late ’50s and through to the end of her life in 2003. Some consider printmaking a lesser art form than say painting or sculpture. How do you respond to this? Does this show seek to refocus scholarly attention toward this aspect of her oeuvre?

AM: I am passionate about printmaking, so I will try to be as objective and brief as possible with my response. Printmaking, in all of its iterations, makes art more accessible—for viewers in a gallery or museum as well as for collectors. This does not make it a lesser art form. The viewpoint that prints are lesser art forms stems, in part, from the monetary value of prints in comparison to paintings or sculptures by the same artist. Prints are less expensive because there are often multiples in circulation. People get caught up in the idea that good art can only be “one of a kind.” These multiples, however, are all original works of art because they were printed from the same block, plate, stone, etc.

I also think that those who view printmaking as a lesser form of art do not understand the complexities involved in making a print. The artist comes up with a composition, then reverses it on the plate so that the resulting print reveals the original composition. Reversing an intricate drawing is not easy. In the early days of printmaking, many were involved in making a print—a designer, a plate cutter, often another person inked the plate, and yet another pulled the final print. Most contemporary artists complete this complex process alone.

The importance of Thompson’s prints within her oeuvre cannot be overlooked. She committed herself to printmaking, and I’ve often wondered if the complexity of the process was what most attracted her. The prints from the Cochran collection are only a fraction of the prints Thompson completed during her lifetime. She also revisited earlier series and reworked the plates, revealing her dedication both the concept and the medium. The “Death & Orgasm” series in the exhibition is from 1991. However, Thompson originally completed the plates in the 1970s. She cut her earlier signature directly into the plate, and it appears at the bottom of each print in the series. As you mentioned, she often worked through her ideas within a single edition. She also worked through her ideas within a series. For me, her paintings encapsulate a concept, while her prints allow the viewer to follow her thought process.

MM: Is there anything else about the show, or Thompson’s work, that you’d like to add?

AM: Nothing that will replace viewing these prints in the flesh. Just come to the show!

“Creating Matter: The Prints of Mildred Thompson” will be on view at the Michael C. Carlos Museum at Emory University through May 17, 2015.

Melissa Messina is an independent curator who divides her time between Savannah and Atlanta, Georgia, and Brooklyn, New York. She is the curator of the Mildred Thompson Estate and created the Mildred Thompson Legacy Project, which seeks to raise awareness for the artist’s work through research, programming, and exhibition and acquisition opportunities.