Created in direct response to the social injustices of the 1960s, Faith Ringgold’s historic series American People (1963–1967) and Black Light (1967–1971) appear together at the Spelman College Museum of Fine Art to signify an unprecedented visual exploration of the intersections of race, gender, and class. The exhibition highlights one of the most tumultuous and liberating periods of the United States’ past, the civil rights era, as a catalyst for challenging discourse and reflection.

I recently caught up with the museum’s director, Andrea Barnwell Brownlee, to discuss the exhibition American People, Black Light: Faith Ringgold’s Paintings of the 1960s. We spoke in person and then followed up by phone and email.

Faatimah Stevens (FT): In the words of Faith Ringgold, generations of artists express—collectively—our history. She suggests that her own work thrives on the experiences we share: “I think that art and artists document the times they live in. It’s from experience that we create art … and what I wanted was to tell my story.” Deriving from a career that spans many decades, her work chronicles the most important times in our American landscape. Looking back, do you consider Ringgold to be a pivotal storyteller for this generation?

Andrea Barnwell Brownlee (AB): By organizing American People, Black Light: Faith Ringgold’s Paintings of the 1960s, exhibition curators Tracy Fitzpatrick and Thom Collins heighten the widespread belief that Ringgold is a storyteller for this generation and beyond. On one hand, works in this exhibition are firmly linked to Ringgold’s experiences that were informed by the civil rights era. On the other hand, during this current era of instant global access, when we seem to value sound bites more, and often seem to appreciate in-depth discussions a bit less, storytelling is a talent that is more vital than ever. As I view the series American People and consider the circumstances that prompted Ringgold to begin creating it in 1963, it is clear that she defies the habit of living one’s life in shorthand. Ringgold’s perspectives on exclusion as well as [on] race and gender discrimination continue to be relevant. It is perhaps easy to lull ourselves into complacency, point to advancements—such as electing the first African American president—and then act as if our sociocultural missions have been accomplished. However, this series is a visual reminder that there is so much collective work still to be done. Works such as American People Series #1: Between Friends, American People Series #5: Watching and Waiting and American People Series #9: American Dream (all completed in 1963), for example, remind us that who is invited to sit at the table still matters and that things aren’t always what they seem. This series also reminds viewers that Ringgold is an expert, patient storyteller who bases her work on thoughtful reflection and introspection. She has honed it as a sophisticated craft and allows it to unfold over the course of several canvases.

The early series on view at Spelman allow us to reflect on Ringgold’s life as an artist, activist, and author and [to] consider these early canvases within the arc of her career. Her quilt Groovin’ High (1986) is one of the most discussed and requested works in Spelman College’s collection. The opportunity to consider this work and chart her artistic evolution from the series of early paintings of the 1960s is really a remarkable experience. When we talk about Ringgold within the context of storytelling, it is important to at least mention her 1995 autobiography, “We Flew over the Bridge: The Memoirs of Faith Ringgold”; “Tar Beach,” her remarkable, award-winning children’s book; and other illustrated children’s memoirs.

FT: Organized in juncture with Ringgold’s 80th birthday, the exhibition focuses upon a period whose works have gone unseen for four decades. These once influential paintings, with only a few notable exceptions, vanished from view, omitted from critical and art historical discourse. In regard to the social and political essence of our time, is this exhibition (the first comprehensive review of these works) long overdue or right on time?

AB: The answer is really both. American People, Black Light: Faith Ringgold’s Paintings of the 1960s is both long overdue and right on time. It is essential to point out that these series did not just happen to disappear from discussions and exhibitions. They were omitted because no one wanted to see or hear about a Black woman’s pointed perspectives about race and gender at the time. It is useful to frame this discussion within that context because their omission was calculated, silencing, and deliberate. Tracy and Thom (co-curators) were well aware that the occasion of her 80th birthday was an opportune time to revisit this work, consider what (if anything) has changed, and ponder the relevance of these works today. Large-scale works such as American People Series #18: The Flag Is Bleeding and American People Series #20: Die suggest how timeless the works in this exhibition really are. Even though Ringgold completed them 45 years ago, they prompt a host of overlapping questions that continue to be relevant today including (but by no means limited to): How is nation defined and who benefits? Who are the innocent bystanders? Who enacts violence? Does a safe haven exist? And, if so, where?

Sociocultural lessons will present themselves again and again. The players and the dates might be different. But the conversations and topics that Ringgold examines will continue to be relevant decades from now: how wealth is distributed, when or [whether] to enter into international conflicts, the amount of resources that are devoted to education, how violence and its perpetrators are handled, how to deal with economic disparities, immigration reform—the list is endless. She prompts viewers of this time to think more broadly about what it really means to be a global citizen. No matter what side of the fence on which you sit, these or similar discussions will continue to be relevant. For this reason, American People, Black Light is relevant and timely.

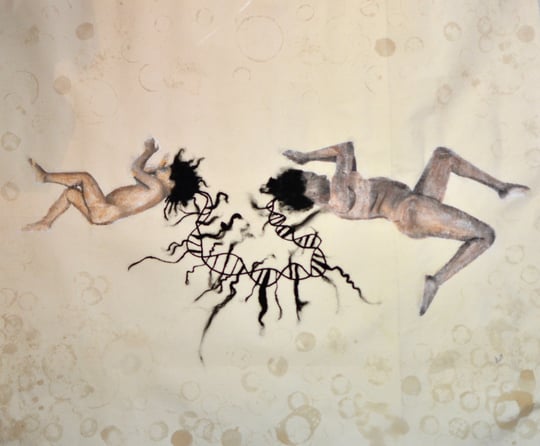

FT: In Big Black (1967), from the Black Light series, Ringgold celebrates the tonal range of African American skin by creating sections of abstracted facial features reminiscent of African masks. This display of facial characteristics is glorified on canvas in nine sections, symbolic of masks on display in households today.

Who is Big Black? Ringgold’s exploration of African features is another way to signify past perceptions of race, or even gender. With wide-open eyes, the portrait could be a child, a daughter, a woman, or perhaps an adult male, awakened by the disturbances of 1967 America. How does the title Big Black change a viewer’s perception of a contemporary portrait?

AB: For me, the most compelling aspect of Big Black is Ringgold’s exploration of the formal properties and capabilities of the color black. I’m not surprised that you singled it out, because it has prompted many discussions around Ringgold’s perceptive investigation about both color and texture. The conversations that I continue to have about this painting and the series in general all revolve around its black paint, its ability to emit light, [and] Ringgold’s keen ability to harness the history of art and situate herself with[in] it. When you see this painting in person, it becomes clear that it is far more complex than any reproduction can convey. It forces viewers to both examine its formal qualities and consider that Ringgold was compelled by her own palette when one didn’t exist. In We Flew over the Bridge Ringgold explained:

In 1967 I had begun to explore the idea of a new palette, a way of expressing on canvas the new “black is beautiful” sense of ourselves. In the painting of Die, I had depended upon the blood-splattered white clothing of the figures to create the contrast needed to express the movement and energy of the riot. I felt bound to [the color white’s] use, having been trained to paint in the Western tradition. But I was now committed to “black light” and subtle color nuances and compositions based on my interest in African rhythm, pattern, and repetition.

As I consider “Who is Big Black,” perceptions of a contemporary portrait do not come to mind. Instead, I marvel that Ringgold has always been candid about her tenuous relationship with the Black Power Movement. She asked herself central questions including, “What was Black Power?” “Can a Black Woman have Black Power?” and “Did I have Black Power?”

FT: Inspired by the American lunar landing in the summer of 1969, Flag for the Moon: Die Nigger is Ringgold’s most notable depiction of her frustrations with the plight of African Americans in the United States. She responds to the costly expense used to land on the moon when poverty levels, particularly among African Americans in the United States, were at their highest.

Consider the title and content of Ringgold’s painting. Subtly she buried the words DIE, in the blue field of the flag, and NIGGER, sideways, in its red stripes. Behind the guise of the American flag, a message of deeply felt dishonor is suggested. Even though a groundbreaking achievement was reached on a summer day in 1969, underlying issues in neighborhoods across America were ignored. Is this work one of Ringgold’s most effective messages for discourse and reflection today?

AB: Flag for the Moon: Die Nigger is among the most discussed works in American People, Black Light. I reflect on a conversation that I had with co-curator Thom Collins when the exhibition was on view in Miami. He explained that if the opportunity to acquire a work from this nationally touring exhibition presented itself, that he would without hesitation select this work. Flag for the Moon is really an examination of contradictions. What’s hidden and obvious? What is visible and invisible? There is a particular moment when people realize that “DIE NIGGER” is embedded in the stars and stripes of the painting. The painting prompts reactions from viewers and underscores the overall tensions that are associated with the word “nigger”: the origins and historic use of the word, who society deems can use the word, the pervasive use of the term “the N word” as a substitute, and the widespread belief that such conversations should only be held behind closed doors.

The flag is an icon that artists continue to engage. By associating the lunar landing and the historic planting of the American flag on the moon with the volatile command “die nigger,” Ringgold unapologetically asserts herself … and protests [the fact] that the country had categorically decided to withhold resources and basic necessities from some of the Americans who were in need the most.

It is useful to discuss Flag for the Moon: Die Nigger in tandem with the large painting American People Series #19: U.S. Postage Stamp Commemorating the Advent of Black Power (1967). Both incorporate text and explore what is hidden and what is obvious and serve as large metaphors for discord and national pride. American People, Black Light places Ringgold’s story quilts within a whole new and vibrant context. It also proclaims: If you think you know Faith Ringgold, think again.