Frontotemporal degeneration (FTD) is a disease that is relentless in the trauma it inflicts on both the person with the disease and the families that care for them. Dashboard executive director and artist Beth Malone has an intimate experience losing her father to FTD and is using her time as a TED Resident to explore the parallels between caring for her father and her immensely influential Atlanta-based organization Dashboard, which organizes exhibitions in vacant, usually commercial, properties. Tori Tinsley, also an artist with an FTD parent, called Beth Malone to talk about her recent acceptance into the TED Residency program, what she hopes to accomplish during her time in New York, and how the cultivation of authenticity is at times a collective effort.

Tori Tinsley: Congratulations on the TED Residency! Tell me what that’s about.

Beth Malone: I did a TEDx talk last September with TEDx Peachtree about Dashboard and the work that we do around the country. Afterwards, a woman who was there from “big TED” invited me to apply for residency in New York, where you work out of TED’s office for three months and give another talk, but on the big TED stage. I applied, really thinking that I had no chance of getting in … but then I got it! It is really exciting, and nice to be here. This time though, I decided that I not only wanted to talk about Dashboard’s work in the arts but about how that work has influenced my relationship with my dad’s illness, and how his illness really influenced my own studio work. I’ve never really dissected that before, but I knew that it was interesting: how things shifted at Dashboard and within my own art practice when my dad got really sick. So, I am still kind of working out these details, but it’s a fun thing, and it’s helpful to have the time to do it.

Tori: Can you talk a little about the residency?

Beth: There are fifteen other people from all over the country who are part of the residency and doing projects across the board—people working in academia, say, studying the effects of “fake news,” bias, immigration or the war on terror. We get to work on different things and share ideas and issues and concepts with each other throughout the course of the day. It’s exciting to get the perspectives of different people who are doing really fascinating work. Something I’ve noticed is that everyone has a very big network. So, if I have questions about something, like, I need to talk to someone who has had family members with dementia, chances are someone in my cohort will be able to answer my question or connect me to someone who can answer my question.

Tori: Could you talk about the connection between your father’s illness and your practice as an artist, and how that plays out in your project?

Beth: When I was applying to TED, I had just done the talk about Dashboard and felt like I had presented so much good information about Dash that I didn’t really know what more to say. I thought it would be more interesting to talk about something a little more personal, like how my father’s illness affected my work at Dashboard. Then within my own artwork, there have been a couple things that I have done over the past few years that really helped me to verbalize, share his illness, process the illness, deconstruct the illness. For me, this is really important because this particular form of dementia is so bizarre, so traumatic. It’s not something that people see every day. It is still relatively rare.

When I did a performance in Philly at the Gingko Parlor last year, I did this silly little stand-up routine talking about how I thought about killing him. The only way I knew how to process it was to make it humorous because it is such a horrific disease that at some point I realized that I had to find humor in it. The audience was either totally put off, like”wow I don’t know how to handle this woman,” or they were people also dealing with something similar. Some came up to me after the performance and said, “oh, I didn’t really know how to talk about this because I feel shame and guilt around it too. It is a really hard thing to process, so it is nice to hear someone talk about it.” I think that, through that performance, talking about it for me was therapeutic I realized that it was something I really wanted to do for this particular TED talk. The most interesting way for me to talk about it was through Dashboard and artwork and the way things have shifted for me and my brain in the past couple of years.

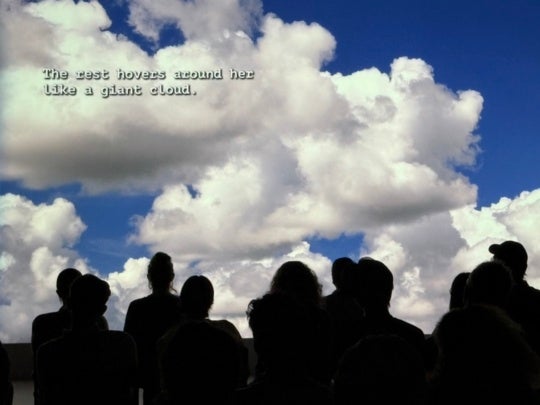

When I hear you talk about your work and when I first saw your work, it was so therapeutic to me because it was like, oh, I can actually talk about this stuff, and we don’t have to talk about it in a way that puts our parents front and center. We can just talk about the disease and these mutations of the disease, and it is not specifically talking about my dad alone or your mom. We are talking about the illness as this very aggressive thing, but we are talking about how it affects people universally. We are talking about how it affects us personally, but we are not—I don’t want to say exploiting — but we are not talking specifically about our parents and their identities. I’m really trying to be mindful of that too.

Tori: That’s something I have struggled with too. I feel a tinge of guilt about dragging my mom into this, but I also want to honor and protect her. It’s a fine line in a lot of ways. Humor is sometimes the only saving grace in all of it. Are you thinking of continuing the performance piece with your TED talk?

Beth: I don’t know yet. Public speaking has always felt a little performative for me because it’s obviously horrifying, right? It is scary to talk to hundreds of people, specifically about stuff that is so close to your heart and that you don’t talk about often. Any time I speak publicly, even about Dash, I feel like I morph into another person and put on this extra professional face. So, I do kind of think of this as an art piece, as a performance piece. I kind of have to or I would cry through the whole thing. It’s a tool to get through it all. I don’t think I will do it as a standup routine though. I think it will be more storytelling. I haven’t quite figured out what my best story is. At the end of the day, I think Dashboard is my most interesting story. I know my talk will have something to do with the stories and memories that buildings hold for us. I think I will probably talk about the home that I grew up in, and then having to move my dad into a home that is no longer his, and how that has been for my family. Meanwhile, I will also be talking about how Dash goes to certain spaces full of lost memories, and how the artists we work with revive those memories.

Tori: I’m interested in what you said about Dash being your best story. Can you talk more about the relationship between your work with Dash and your dad’s illness?

Beth: He got really sick three years ago … I think. I’ve lost track of time over the past three years; it has been so traumatic. He has been sick for fifteen years, but we only had to move him out of his home about two years ago. He’s been living in a nursing home since then. He’s been so sick that we’ve had to have someone stay with him, and I would go a couple times a week. It was a lot. When I started thinking about this talk and what to do with it, somebody asked me how has this illness affected Dashboard? I had never thought about that. So, I’ve been trying to go back through the stuff that we’ve done and thinking about what I was processing at the time. I think I’m going to formulate this by going back through a couple of the shows we have done and create parallels between those and what was happening with him at the time. I’ve realized that I was getting obsessed with archiving and preserving people’s stories with Dashboard.

We did a show called “Nexus, Sexus, Plexus.” I got so obsessed with telling the stories of Atlanta’s art history and wanting to preserve people’s stories and make sure they were heard. I think that is a direct response of me being afraid my dad’s story wasn’t going to be heard. I also did a Truck Talk program with Atlanta Contemporary, where I was interviewing people in my truck and recording their oral histories. I think about the parallels between different exhibitions I was doing and him being unwell — but also me being unwell — and how the artists Courtney [Hammond] and I worked with really helped me to get through it by doing the work. The project we did in Detroit involved site-specific installations in response to a particular building and to the city. I stayed there for eight months, and I dug in and made a good group of friends and really committed to that place because again, I just wanted to make sure that the story being told was authentic and the one they wanted to tell. I think that directly responds to the fear I was having about my dad not getting to tell his story. I kind of skipped out because it was too heartbreaking to see him in the nursing home. I had a lot of guilt about leaving my best bud in this horrible place. I think that’s why I committed to telling the stories of these other people, because I had this guilt and wanted to pay homage to these people and their stories. I don’t know if any of this makes sense, I really don’t.

Tori: To me it makes complete sense! You’re talking about authenticity and people being their authentic selves. I feel like I lost the authentic mom I knew. I feel you are wanting to give people the opportunity to focus on that and I think it’s a beautiful way of connecting people with themselves.

Beth: I hope so. It’s been tricky finding the best story because there’s so many different options.

Tori: I understand the guilt, I have immense guilt and that’s why I focus so much on my own story with this disease in everything I do. It’s exciting that you’re getting to focus on your experience too. Does it feel like the right time? You’ve been working on these related things, and I know you’re excited about this next project, but this is going to be something more personal.

Beth: That’s such a good question and maybe this is something you’ve gone through, too, where for a while he was all I could think about. I’d wake up thinking about him in the nursing home. I felt so unhealthy and afraid, so heartbroken for so long. But then I started to process it more. As you know, this disease makes people lose their ability to speak and ability to form language. All of these things get lost. So, I made a couple pieces about the deconstruction of language and how inadequate language can be. People responded to hearing about it, and we did so many beautiful exhibitions with Dash that I started to feel better. In the past few months, I’ve been feeling okay with where he’s at and knowing that he’s really in the safest possible place. He’s gotten really calm lately and my family is healing.

When I first got to New York I was like, “is this really something I need to talk about? Do I need to drudge up all this pain when I feel pretty okay? I feel pretty calm. I’m not devastated.” Then I realized it’s probably the perfect time to do it because when you’re in the middle of the shit storm and you’re spinning around and you’re telling everybody about it, and you’re making artwork and you’re telling all the artists you’re curating about, it’s kind of a mess. You’re a sloppy little mess. So, coming at it from this new perspective of peace and acceptance allows more reflection. I can think about it critically and about how it truly has affected the past couple of years of my life and my work. So, I do feel like this is as good a time as any. I still want him to be fresh in my brain. I still want this very big transition in my life and my family’s life to be fresh in my brain. So that I can tell the truest story that also really honors him. I think that’s the biggest goal, to make sure there’s a story here for him, and how he has really influenced my work forever. He’s been such a good and amazing role model. He’s forever an amazing impetus for me to act.

Tori: What you’re saying is so beautiful.

Beth: Do you ever wonder if people will understand this? Does it feel universal to you? Am I just being really indulgent, or am I telling a story that people will say: “I get it, this is really helpful”?

Tori: I’ve been trying to figure that out for so long … what to say. There are so many facets of this whole experience and so many ways you can explore or talk about it, depending on what’s going on. I’ve decided to be self-indulgent and I’m fine with that. I do create these pieces that are for me, but it’s nice that I’ve found ways for other people to bring their own stories to my work. I think that was a happy coincidence. I really love it when people can say “I totally know what you’re talking about” or “I have someone in my family who’s going through something similar.” I like it when there’s that bit of dialogue. But at the same time, like you were saying with your performative piece, some people are shut out and they don’t want to know any more after they know the background behind it. They’ll think it’s funny and then they learn about it and run away, and that’s just part of it. I think this is a discussion that needs to be had, maybe not specifically about this disease but about caring for a parent. This may become the norm as they age. If we can talk about it, then it’s not as scary and we’re not as alone and we have better resources. That’s my hope. And I totally get what you were saying earlier about the dark side of it, of wanting to put your dad out of his misery. I have similar thoughts on a regular basis.

Beth: That’s a conversation I have weekly. As soon as you said it’s okay to be self-indulgent, my body relaxed. I think about your work, and that people don’t know the story of it. You still have these really gorgeous paintings. I know that I have a good story in Dash, and I don’t want to take away from that story by adding this new layer, but I do feel like I want to process and talk about the way that grieving affects us, and the way that it improves us. I guess I’m preparing too, because at some point he’s going to pass away. It doesn’t seem as scary when we really talk about death and illness. We’re children of baby boomers and they’re aging. At some point, it’s going to start happening pretty rapidly. I think talking about it makes everything a little bit sweeter; it keeps everybody vulnerable and open for present-tense living and loving harder. I think I’m convincing myself that it’s okay that I’m going to talk about this.

Tori: If it changes, that’s okay. It sounds to me that it can only enrich your practice as a curator and as executive director of Dash. I foresee only positive things from this. I’m sure that it will be painful along the way, but I’m very excited for whatever follows. It’s not easy to do.

Beth: I think in the calm and peacefulness comes from submitting to the disease; I submit that he’s sick, and I can see myself forgetting bits of him.

Tori: I’ve found a very similar thing. I’ve forgotten, except in dreams, who my mother was. I have to make the time to meditate and focus on trying to recoup those memories. It’s important.

Beth: My older sister, Penny, made this really beautiful book a couple of years ago about dad. On every page, there’s a picture: a spread of me and dad, and Katy and dad, and mom and dad, and Penny and dad, and the kids and dad, and his grandkids. It’s so sweet, and it looks like a book about our dad, but really, it’s a book about our dad for her kids. She wants to make sure they know who Poppy was. It was her intuition to create this story for her kids about him, and I think my intuition is to create this story about me and him.

Tori Tinsley is an artist and BURNAWAY’s Outreach Coordinator.