I recently sat down with close friend and fellow artist David Onri Anderson to talk about his painting practice. David is from Nashville and still calls it home. He’s a prolific painter and recently had a solo show at the Fluorescent Gallery in Knoxville. In addition to his own work, David runs a gallery out of his basement, the Bijan Ferdowsi Gallery, and also helps curate and run the artist-run space Mild Climate.

Matt Christy: Did you always paint on everything?

David Anderson: On everything …

Maybe that’s too broad. Are you more choosey about what you paint on than I’m giving you credit for?

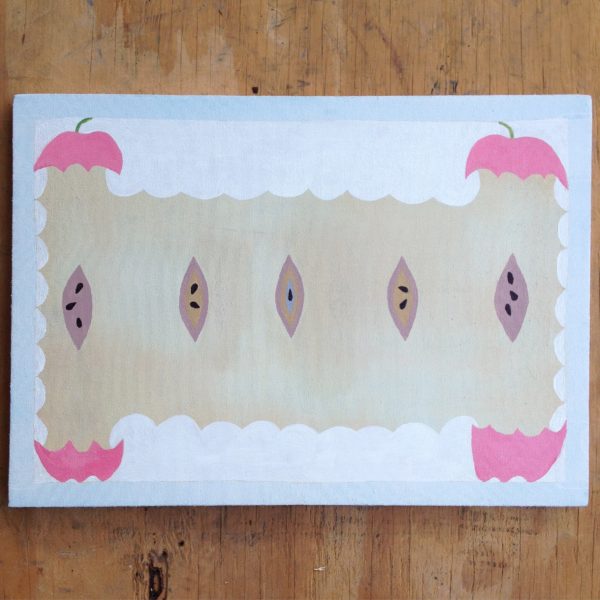

I think I have some criteria, but it could pretty much still be anything. Like, I’ll paint on a rock and a baking sheet and a loose piece of silk. I’ll see something or find something on a walk and for some reason it compels me to paint. It has a power that’s not all my intention. And I figure out that source of being compelled through painting.

Like the chip bags?

Yeah. I discover some potential. That makes life better or richer. I discovered chip bags can be great paper lanterns. I relate that way of thinking to Isa Genskin or Richard Tuttle. When I was younger, those people blew open my mind to the fact that a piece of string can hold a lot of gravity and space. In your daily life you don’t think that because you’re trying to find food or money or something. But in this art space, all of a sudden you can place a higher value on things that are otherwise not very valuable. But if you believe everything is valuable, you can figure that out through art.

So you elevate a chip bag from its trash position?

Yeah, like finding Buddha in a chip bag.

Do you think elevate is a good metaphor?

I don’t know. It’s hard. I would say yes, but at the same time it doesn’t need to be above. It’s horizontal. It goes back to my soup metaphor; everything is soup. That’s the politics, it’s just everything is in a broth and you take a spoonful of whatever and it’s all soup but it’s all different ingredients.

So it’s all necessary.

Yeah, it’s all individual but it’s all part of the soup.

But what happens when there’s poison in your soup?

That’s hard. That’s a real thing. You might have poison mushrooms in there. But when you make the bowl of soup, it’s good to know which mushrooms are good to pick and which are not.

I like all your food metaphors. You seem to use it in a therapeutic sense.

I guess it’s like a deep therapy. Because for me, the preparation of food is very therapeutic. When you make food you’re not thinking about yourself, you’re thinking about all the things you gotta do. You gotta chop up the garlic and think about when it goes into the heat. You think about the flavors and how they work together. For me, all those criteria apply to good art too. And food is spiritual as well as physical. When you eat food that’s really processed, and just eat hastily while watching TV, you don’t get the spiritual energy. You just feed your mouth and check it off your list or whatever. But it’s a big process, the actual ingredients integrating with your body. It’s holistic. There are lots of things going on. Recently, I’ve met a lot of artists that are great painters and great cooks. Hmmm. You can make a great curry and a great painting, interesting.

There’s a Dubuffet quote about cooking and its relationship to art: “If you serve someone spinach that is cooked the way it should be, no one notices or remembers that they have eaten spinach. Whereas if you burn it, it shocks their taste-buds and they become immediately aware that it is burned spinach and they gain new insights into the characteristics of spinach, cooking, etc.” (1) Dubuffet is talking about making it indigestible so you see it in a new way. I think you’re talking more about a sort of generosity.

The way I was raised, my mom was from France and she loves French cooking and her dad is from Algeria. There’s this African French cuisine that’s spicy and so buttery and always has really warm rich flavors. My mom’s idea of loving people is to make good food and everything else happens around that. So food, that’s my way of connecting with creativity and what’s good. It’s weird we think about what’s good with food. But the generosity is what I look for in life. I want to find something that helps me generate.

Generosity and generate.

I don’t know why Dubuffet would want to make indigestible art. Maybe there was a time that was necessary.

I think it’s a different approach to an audience. I think part of it was breaking down the propriety around painting and bringing in things that were being suppressed and denied.

I guess to me that’s not about making burnt food but just realizing rice and beans is where it’s at, and you don’t need lobster or something. To me, what he did was still creative and beautiful but it’s raw, like raw vegan food. It’s slightly scary. It’s the way bananas were before we processed them so much, they had huge seeds and were not so easy to eat, but we made them into little candy bars. I think his paintings are about those wild bananas.

There’s an emptiness to some of your images. Don’t you think?

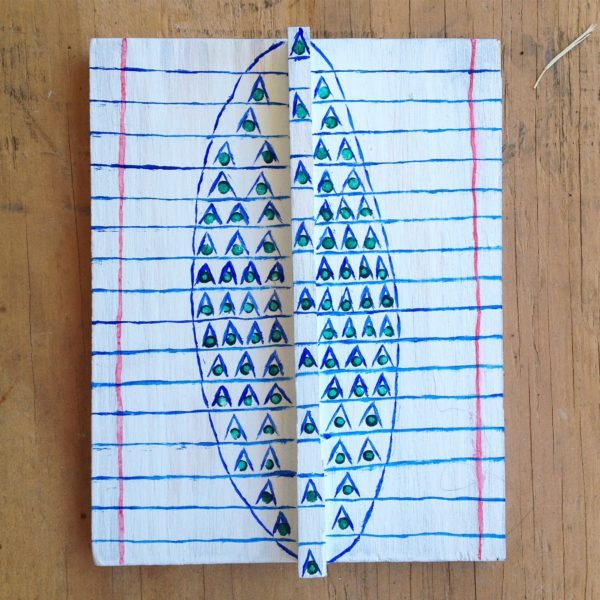

I would say my subject is emptiness. I wanted to somehow imply that my paper lanterns are infinitely empty.

I’m surprised you don’t get more blowback because of that.

No one talks about that.

It can potentially frustrate a viewer. A viewer can say, it doesn’t give me enough to go anywhere, it just alienates me, it doesn’t tell me anything.

I think there are some artists who make pieces thinking they are about something, and there are other pieces they make that they know are empty. I feel like there are lots of artists who want their art to be about everything, but that sort of stuff makes me uneasy because its feel like it’s delusional, or like the art thinks too much of itself or something. So I want to make art that doesn’t think anything of itself.

But what about art that is about something, like say, the politics of a river. I think there’s an implied moralistic imperative sometimes when you are going through an art education, and it’s like the world you’re building is isolated in some ways.

That’s a way of thinking about it that could be at fault. But I think emptiness is the opportunity for anything to happen. Art should not be an object or an obstacle but a space. And Space to me is emptiness. When you experience one of my pieces because it has a space your mind can settle in, it involves you.

But it’s not a literal space. Why don’t you make literal spaces?

I guess I feel like I’m already in the space. I want to get to a deeper understanding of space, so that when you’re in the space looking at the object your mind can go into it. It’s more like the definition of space. And to me, a necessity of meditation or contemplation is to realize that you have a quiet or calm space in your mind no matter what is going on around you and no matter what emotion you’re feeling.

It’s an imaginative space. Since you aren’t doing installation work.

Yeah, that would take out half the journey.

Do you see your paintings as resistant to certain things?

Yeah.

What do they resist?

I think they want to resist technology and being beholden to new media. They want to resist trends and the need to be monumental or spectacular. They are resistant to being promiscuous and to being … infatuated. They just want to quietly have a conversation with you before they know whether or not they like you or love you or only want to be associates or something.

Can they love you?

They can love you, yeah. Some pieces are so ready to love. But they aren’t all the same. Some of them just want to go to the lake with you and not even talk. I don’t know. I don’t think about making an art piece about something. It’s just the character of this thing.

Why promiscuous?

I see that as something that is popular. It’s expected, assumed even. Like it’s a joke if you’ve only slept with one person, where in other cultures that’s the norm. I’m not judging promiscuity as right or wrong, I’m just saying it’s something that has taken hold. I see my paintings as just wanting to be one thing not a bunch of things.

They’re monogamous paintings?

Yeah. Promiscuity takes something that is intimate and special and rare and de-rarifies it. It’s like wanting a bunch of truffles. But one truffle is a whole lot.

If you’re promiscuous enough you want all the truffles.

Yeah, and I see some paintings go after a bunch of truffles all at once. My paintings know that one truffle is enough.

Or to be so still that just an element of the truffle is enough.

Yeah, like the smell of a truffle making you feel full for a week.

- Dubuffet, quoted in Margit Rowell, “Jean Dubuffet: An Art on the Margins of Culture”, pp.15-34 in Jean Dubufet: A Retrospective, New York, 1973, p. 23