The English translation of this article directly follows the Spanish.

Comienza con el coro de coquíes, un sonido que gotea cuando se aproxima la noche, anunciando el giro que dirá el día con la intensidad y cadencia crecientes de una cascada. En una habitación poblada por el equipo de producción—las cortinas amontonadas, las pantallas de las lámparas inclinadas—una joven está enervada en un sofá, con una pila de libros entre sus rodillas explayadas. Su apatía es una fatigada aquiescencia. La mano que descansa sobre su corazón podría denotar ansiedad; sus ganas de moverse señalan que es una de esas ansiedades que te tumban. Su marido, fuera de cámara, declara que se marcha para siempre. Ella ya le había rogado que lo reconsiderara. Ahora está resignada, sin la energía ni las ganas de seguir peleando. A medida que se desarrolla la escena, la directora—la madre de la actriz—aparece en un segundo cuadro, asintiendo con la cabeza mientras observa. En esta escena de Retiro, la película multicanal de Natalia Lassalle-Morillo, la artista retrata brevemente a su madre, Gloria Morillo Cabán, el foco de la obra y la coescritora. Retiro tiene un título intencionalmente ambiguo, que se traduce en inglés como “retreat” o “retirement”, como verbo o nombre; el proyecto en curso, nacido en 2015, incluye la película terminada y sus presentaciones en cambio constante. Esta parte tiene el carácter de un palimpsesto, un hilo de la primera encarnación de la película: la reconstrucción que realiza Natalia de un momento fundamental de la vida de Gloria, dirigida por la propia Gloria.

¿Cómo nos convertimos en nuestras madres? Estoy fascinada con el comienzo de la vida: un bebé en el útero contiene, en sus ovarios, todos los ovocitos que su cuerpo alguna vez convertirá en óvulos (la poeta boricua Julia de Burgos describió el Río Grande de Loíza —en su poema del mismo nombre— como “mi manantial, mi río / desde que alzome al mundo el pétalo materno”; tal vez estaba haciendo referencia a este florecimiento de un capullo preexistente). Cuando mi propia madre, enfermera y partera educadora, me leyó estos versos, me estaba contando una historia, un dulce mito etiológico que nos uniría a la matria. Aunque solo he estado allí dos veces, anhelaba reconectarme con Puerto Rico, donde ella nació. Hace mucho convivimos allá, cuando yo nadaba en las aguas de su vientre. La veracidad no es el punto; tampoco fue un elemento determinante en los cuentos de mi abuela traídos desde el archipiélago—recuerdos fantásticos de visitas espectrales de antepasados, un terremoto que se tragó a una niña desatendida—; aunque ella insistió en que estos recuerdos cuasi-ficticios de Borikén eras historias reales.

Me atrae Retiro con su matriarca boricua que escribe su propia historia. En otro punto de la película, se establece que la escena inicial, aunque técnicamente biográfica, está entretejida con las manipulaciones artísticas de Gloria. De hecho, sus instrucciones directivas se nos presentan por los múltiples canales de Retiro. En una conversación reciente, Natalia, cuya formación es teatral, dijo que está conmovida por lo que ella llama “la viveza” o la convivencia de muchas realidades vividas en el espectáculo, el cine y la vida y, especialmente, en Puerto Rico. Es “La última década de tragedias —y los siglos precedentes de colonialismo— nuestra desconfianza en el gobierno, la importancia de contar nuestras propias historias: Borikén es un lugar donde la ficción y la realidad se han fusionado”, explicó. Este es un concepto que explora gracias a una investigación artística del Smithsonian de 2021 (2021 Smithsonian Artist Research Fellow), que le posibilitó estudiar objetos ceremoniales de las prácticas del Voudoun haitiano y el taíno Arahuaco y cómo se conectan inherentemente dentro de una visión amplia de la cosmología caribeña.

Para Retiro, explicó Natalia, “Quería crear un nuevo archivo de historias puertorriqueñas, uno que honre nuestras cuentos, nuestros mitos … [mientras] simultáneamente busco formas para que mi mamá y yo nos entendamos. Le dije que podía reescribir su historia; Quería entregarme a su narración”. Este acercamiento es clave para el método de Natalia a lo largo de su práctica e investigación: la forma en que la realidad y su construcción se mezclan, el potencial de renovación en una narrativa recontada. Con su reiteración alquímica del pasado, Retiro archiva una cronología casi mítica de Gloria durante los últimos años, que es a la vez factual y quimérica. Esta película prismática es también el intento desde el corazón de una hija de vincularse con su madre a través de la colaboración creativa, invirtiendo la típica relación cineasta-sujeto, para dar a luz algo nuevo.

En 2013, Natalia estaba estudiando teatro experimental en la Universidad de Nueva York y asimilando la conclusión cargada a la cual llegan muchxs: me estoy convirtiendo en mi madre, un horror y una bendición. Sintió que la distancia entre Nueva York y Bayamón, Puerto Rico, su ciudad natal, reflejaba el espacio entre ella y Gloria, su creciente tensión generacional, el tramo de millas de su historia compartida. Al incursionar en el cine después de graduarse, Natalia exploró la experiencia entrelazada de la maternidad y el ser hija y se vio impulsada a trabajar directamente con Gloria para desentrañar sus traumas solapados y conocerse a profundidad. Tras el fallecimiento de su madre (la abuela de Natalia), Gloria estaba en duelo: “Ella había perdido su origen”, dijo Natalia. Natalia regresó a Puerto Rico en 2015, mientras consideraba un nuevo proyecto del cual Gloria sería musa y colaboradora. “Estaba pensando en el teatro”, dijo Natalia.

“¿Qué pasaría si comenzara a trabajar con ella de una manera que no se enfocara en este dolor o este trauma, sino en la reconstrucción de la historia? Estaba pensando en crear una ficción a partir de la realidad, difuminando las líneas entre los dos para formar algo nuevo, en vez de recontar el pasado. También siento que Retiro fue un intento consciente de enlazarme con mi madre, de tratar de verla, no como esa persona con la que estaba en conflicto o en la que simplemente me estaba convirtiendo”. Natalia es parte de una creciente ola de artistas en Borikén que se reconectan con sus ancestrxs, reinventando sus recuerdos para comprender mejor el presente. “Sobre todo”, explicó, “quería recordarle a mi madre su brillantez”.

Gloria nació en San Juan, Puerto Rico, “en los años cincuenta”, me dijo en una entrevista reciente. Explicó que cuando Natalia, su hija menor, nació en 1991, “estuve muy feliz de tener una hija porque eso era algo que desde pequeña había querido. El embarazo fue un poco difícil. Me tuvo que atender un especialista, pero finalmente tuvimos a esta bebé y la quiero mucho”. Gloria, que ya no trabajaba fuera de casa ya que tenía un título en ciencias ambientales, esperaba pasar más tiempo con sus hijos, continuó satisfaciendo sus demás pasiones e intereses. “Exploró de todo”, dijo Natalia. “Hizo repujado de metal. Horneaba. Era brillante en todo lo que hacía”. En 2007, Gloria cumplió un sueño de muchos años de tomar clases de pintura y, en 2009, regresó a la Universidad de Puerto Rico para estudiar ciencias políticas, matriculándose en cursos de filosofía e historia de Puerto Rico. También dedicó tiempo a nutrir su arraigada inclinación hacia las artes visuales y la escritura. “A medida que avanza la vida y uno gana más experiencia”, dijo Gloria, “estos conceptos se incorporan a lo que eres. Se vuelven parte de ti”. Luego, se inscribió en un curso de cine, fortaleciendo su conocimiento del medio.

Al concebir la escena inicial de Retiro, en la que se disuelve un matrimonio, Natalia le había pedido a su madre que seleccionara un momento “trascendental” de su vida. Con base en este evento, harían una película. Gloria inicialmente había escogido el nacimiento de su hija, pero las limitaciones presupuestarias no permitían que se realizara esa visión. Eligieron otro momento decisivo, explicó Gloria, “una experiencia muy difícil de la que pude salir. Exitosamente. Sanada”. Mucho antes de que nacieran Natalia y su hermano, Gloria se casó joven y deliberadamente en contra de los deseos de sus padres. Cuando Gloria discutió conmigo el eventual divorcio, lo describió como un período de esperanza y metamorfosis personal, un corazón roto a temprana edad que se transformó en una fuerza. Gloria se describió a sí misma como “una luchadora. Algo que quizás es traumático puede tornarse en algo positivo “. Natalia estaba de acuerdo y explicó: “Le dije, hay algo que se puede trabajar aquí, en términos de realinear tu relación con este momento, que quizás recuerdes como traumático”. Con Gloria detrás de la cámara y su pasado frente al lente, ella es la artista y la historia se hace maleable. Natalia-como-Gloria entra en una bañera con su vestido de novia, como quizás lo hizo, o no, Gloria, hacía décadas. Se ríe y llora: un desahogo eufórico. Gloria se ha liberado.

En 2016, escribieron y filmaron la película en Miami, Florida. Natalia, que vivía entre Miami y Montreal, Canadá, se mudó a casa después de su finalización para continuar entrevistando a Gloria sobre “su proceso de envejecimiento, cómo se sentía sobre el futuro y cómo se sentía sobre la situación política en Puerto Rico”. En la versión actual de Retiro, estas conversaciones, que se habían eliminado en el primer corte, están en todas partes, entrelazadas con escenas del cortometraje de Gloria y fragmentos del proceso de edición, incluyendo el equipo de filmación que está crucialmente visible en la escena inicial. La revelación del proceso de producción de Retiro hace que la fábula situada en su centro sea asombrosa y disloque—un núcleo anidado en su propia deliberación creativa, que se muestra en tres canales simultáneos. “Hay algo de ficción”, agregó Gloria, refiriéndose a sus elecciones imaginativas para el guion y su conciencia de que la mujer de la película “ya no soy yo”. El realismo aparentemente orgánico (a veces árido) del documental se ve influido por las meditaciones de las mujeres y la divulgación de su proceso. Juntos, estos dos aspectos forman una tierna carta de amor mutuo de Natalia y Gloria. Ningún momento se presenta sin la mecánica o las preguntas que le dieron forma: Gloria está en el jardín junto a flores floridas y azulejos azotados por la lluvia; en un cuadro adyacente, están las preguntas subtituladas de su hija.

Gloria flota en el mar, a horcajadas hay tomas de la costa y un pequeño sol abrasador, en que las indicaciones de Natalia son audibles. La actuación periscópica central presenta, en un cuadro, a Natalia como la joven Gloria; en otro, a Gloria, la directora con auriculares y un cigarrillo; y, en un tercero, vemos a Natalia preguntando, en español: “¿Por qué tú escogiste este momento en particular?” El corazón palpita al vislumbrar lo que ocurre tras bastidores.

“Retiro se convirtió en una forma de proximidad, una manera de acercarnos y profundizar en nuestra historia colectiva e individual”, dijo Natalia. “No sabía que iba a tener que crear tanto espacio para su dolor, incluso encarnándolo. Ese acto de entrega consciente cambió la forma en que nos relacionamos”. Las aparentes capas de la película permitieron a Gloria y Natalia verse a sí mismas por separado y mutuamente: su agencia creativa compartida, la reverencia por su hogar, el desenmarañamiento de sus pasados y la intimidad de analizarlo juntas, el lirismo de Gloria, la insistencia de Natalia. A mitad de la película, Gloria sostiene rosas rosado-rubor en el cementerio, sus palabras subtituladas en un marco contiguo: “Tu abuela me decía que esperaba la muerte. Yo no estoy esperando la muerte. Estoy esperando una evolución”. En otro marco, Natalia pregunta: “¿Tú hubieses querido que tu vida fuese diferente?” “A veces si, a veces no. […] Son cosas que pasan.” Gloria enumera sus deseos y cómo la urgencia de éstos se profundiza: “Quiero nadar, rebajar, dejar de fumar. Disfrutar más la vida. Sacar de mi mente las sombras que me atormentan”.

Con el tiempo, vemos un cambio de humor suave, pero perceptible, particularmente en las imágenes filmadas después de los huracanes Irma y María a finales de 2017. “Mi mamá me dijo que había una brecha entre las personas que éramos entonces y las que somos ahora”, dijo Natalia, “llena de revoluciones políticas, una pandemia, terremotos y huracanes”. En estas escenas posteriores, juntas viajan por la neblina de las cimas de las montañas de Borikén, nadan en sus aguas. Puerto Rico es el tercer personaje de la película. Las dos mujeres se transforman en una especie de parábola, un continuo intergeneracional de roles sincrónicos. Natalia le dice a su madre: “Mira el mar”. Se irritan mutuamente. Se vuelven más cercanas.

El verano y el otoño pasados, Retiro se expuso en Hidrante, una galería en San Juan, como parte de la exposición individual del libreto escrito por Natalia, Guión escrito, aún no existe—la primera presentación del proyecto en Puerto Rico. Los canales de la película se proyectaron en tres “pantallas”—persianas verticales, frente a las ventanas, que se podían ver desde dos mecedoras. “Como debe ser vista”, dijo Natalia. “Tienes que venir al espacio y tener la disposición para verla”. Antes, el espacio que hoy día es Hidrante fue un hogar, y su domesticidad previa es palpable. En lo que se sentía como la penumbra y el silencio vespertino de una sala, los ojos de un espectador flotarían sobre las pantallas, absorbiendo a Retiro incrementalmente. Mientras escribo este artículo, la exposición todavía está abierta con un componente pronto a incluirse que, como el título, aún no existe. Gloria y Natalia se encuentran actualmente realizando ejercicios performáticos, dirigidos por el primo de esta última, Ángel Blanco, un coreógrafo, bailarín y sicólogo. Ángel está “extrayendo gestos del lenguaje corporal de Gloria y creando un glosario”, que Natalia memorizará e incorporará somáticamente a gestos tomados del ballet. Natalia explicó: “Es un intento de traducir el proceso de realización cinematográfica en una actuación en vivo y cambiar los roles preestablecidos por la dinámica en Retiro“. Natalia volverá a ser su madre “más allá del diálogo verbal”. Esta vez, Gloria no solo es directora, sino también directora de fotografía, que sostendrá la cámara y filmará a su hija.

Cerca de la sala de proyección, Natalia se refiere a una sección de la exhibición como “La habitación de Gloria”, cuyo título oficial es Estamos desarmadas, meciéndonos en un columpio de ilusiones, una anotación de Gloria—decorada con muebles de la casa de sus padres y pintada con un color vino tinto cálido, como una tripa. Un proyector de diapositivas de 35 mm proyecta imágenes de varios materiales de archivo sobre la pared: las fotos de una Gloria adolescente, el sonograma de Natalia, las ilustraciones de Gloria y sus notas garabateadas al calce de uno de los primeros guiones de la película. Muchas de las notas de Gloria son lapidarias con sus reflexiones sobre el cine y la existencia, que poseen una cualidad filosófica. “La conciencia de lo que uno tiene dentro de una, de lo que es el tiempo de Retiro, ha cambiado”, dice una. Algunos aluden al terreno psicogeográfico de Borikén: “…Mapas, de la región del caribe, con todas las fallas geológicas subterráneas, que nos plantea nuevamente, y nos recordar, que somos bien vulnerables”. Parece que Gloria ha expuesto su corazón en el papel, aunque podríamos estar leyendo su poesía: “Aquí nos encontramos, enfrentando la ficción que hemos creado de nuestras vidas”. Sus palabras imparten un archivo escrito, que rima con la cinematografía de Retiro, de madre, hija y la archipiélaga de Puerto Rico, que también es una matriarca. Una suena como una melodía: “Porque todos cambiamos/ en el transcurso del tiempo/ e incorporamos a nuestra vida/ cosas irrelevantes que nos marcan,/ pero hay otras cosas que se mantienen/ esenciales/ que van a la médula de lo que una realmente es”. A medida que avanzan los créditos del título, resurge la canción nocturna de los coquíes, evocando una tierna tradición maternal: una canción de cuna.

It begins with the chorus of coquis, Puerto Rico’s beloved frog, trickling in the way it does at night, heralding the turn of the day with increasing volume and the tonal cadence of a waterfall. In a room bustling with a production crew—curtains shoved, lampshades atilt—a young woman is enervated on a couch, her knees splayed with a pile of books between them, her listlessness a weary acquiescence. The hand to her heart might denote anxiety; her unwillingness to move means it’s the sort that topples you. Her husband, unseen, declares he’s leaving for good. She’d begged him to reconsider. Now she’s resigned, stretched thin. As the scene unfolds, the director—the actress’s mother—appears in a second frame, nodding, watching. During this scene of Retiro, Natalia Lassalle-Morillo’s multichannel film, the artist briefly portrays her mother, Gloria Morillo Cabán, the subject and cowriter. Retiro is intentionally ambiguous in title, translating in English to “retreat” or “retirement”; the ongoing project, born in 2015, comprises the completed film and its ever-changing presentations. This part is palimpsestic, a thread from the film’s earliest incarnation: Natalia’s reconstruction of a pivotal instance from Gloria’s life, directed by Gloria herself.

How do we become our mothers? I’m fascinated with the way life begins: a baby in the womb holds, in her ovaries, all the oocytes that her body will ever grow into ovums. (The Boricua poet Julia de Burgos described the Río Grande de Loíza—in her poem of the same name—as “my wellspring, my river / since the maternal petal lifted me to the world”; perhaps she was referencing this blooming of a preexisting bud.) When my own mother, a nurse and childbirth educator, shared this with me, she was telling a story, a sweet etiological myth that’d yoke us to the motherland. Though I’ve only been twice, I’ve yearned to reconnect with Puerto Rico, where she was born; we once lived there together, when I was in the waters of her womb. Veracity isn’t the point; nor was it a factor in my grandmother’s tales from the archipelago—fantastical memories of spectral visits from ancestors, an earthquake that swallowed a wandering girl—though she insisted on their truth, these quasi-fictional recollections from Borikén (the land’s Indigenous name).

I am drawn to Retiro, to its Boricua matriarch writing her own history. It’s later established in the film that the opening scene, though technically biographical, is woven with Gloria’s artistic manipulations; her directive instructions, exposed to us in Retiro’s multiple channels, make this plain. In a recent conversation, Natalia, whose bedrock is theater, said that she’s moved by what she calls “liveness,” or the coexistence of many lived realities in performance, film, and life, and especially in Puerto Rico. “The last decade of tragedies—and the preceding centuries of colonialism—our mistrust of the government, the importance of telling our own stories: Borikén is a place where fiction and reality have melded,” she explained. This is a concept she explores as a 2021 Smithsonian Artist Research Fellow, studying ceremonial objects of Haitian Voudoun and Arawak Taíno practices and their inherent connection within a broad view of Caribbean cosmology.

For Retiro, Natalia explained, “I wanted to create a new archive of Puerto Rican histories, one that honors our stories, our myths…[while] simultaneously searching for ways for my mom and I to understand each other. I told her that she could rewrite her story; I wanted to surrender to her storytelling.” This approach is key to Natalia’s method throughout her practice and research: the way reality and its construction commingle, the potential for renewal in a retold narrative. With its alchemical reiteration of the past, Retiro archives an almost-mythical chronology of Gloria over the last several years, equally factual and chimerical. The prismatic film is also a daughter’s heart-centered attempt to bond with her mother through creative collaboration—inverting the typical filmmaker-subject relationship to birth something new.

In 2013, Natalia was studying experimental theater at New York University and reckoning with a fraught realization that befalls so many: I am becoming my mother, both a horror and a blessing. She felt that the distance between New York and Bayamón, Puerto Rico, her hometown, mirrored the space between her and Gloria, their growing generational tension, the miles-long stretch of their shared history. Dabbling with filmmaking upon graduation, Natalia explored the intertwined experience of motherhood and daughterhood and was compelled to work with Gloria herself, to unpack their overlapping traumas and know each other more deeply. After the passing of her mother (Natalia’s grandmother), Gloria was grieving; “She’d lost her origin,” said Natalia. Natalia returned to Puerto Rico in 2015, considering a new project for which Gloria would be muse and collaborator. “I was thinking about theater,” Natalia said. “What if I started working with her in a way that isn’t about this grief or trauma, but about reconstructing history? I was thinking about crafting a fiction from reality, blurring the lines between the two in order to form something new, as opposed to retelling the past. I also feel that Retiro was a conscious attempt to thread myself to my mother, to try to see her not as this person I was in conflict with or simply becoming.” Natalia is part of a growing wave of artists in Borikén reconnecting with their ancestry, reimagining their memories to better comprehend the present. “Mostly,” she explained, “I wanted to remind my mother of her brilliance.”

Gloria was born in San Juan, Puerto Rico, “in the fifties,” she told me in a recent interview. She explained that when Natalia, her younger child, was born in 1991, “I was very happy to have a daughter, because that was something I had always desired since I was young. The pregnancy was a little difficult; I had to be followed by a specialist—but finally we got this baby, and I love her very much.” No longer working outside the home and hoping to spend more time with her children, Gloria, who already had a degree in environmental science, continued indulging her other passions and interests. “She tried everything,” said Natalia. “She did metal embossing. She did baking. She was brilliant in everything she did.” In 2007, Gloria fulfilled a longtime dream to take painting classes and in 2009 went back to the University of Puerto Rico to study political science, enrolling in courses in philosophy and Puerto Rican history. She also spent time nurturing her deep-rooted inclination toward visual art and writing. “As life goes on and you gain more experience,” said Gloria, “these concepts are incorporated into who you are. They become part of you.” She later signed up for a cinema course, enriching her knowledge of the medium.

In conceiving of the opening scene of Retiro, in which a marriage dissolves, Natalia had asked her mother to select a “transcendental” moment from her life. They’d make a film about it. Gloria had initially chosen her daughter’s birth, but budget constraints wouldn’t allow for that vision. They selected another turning point, Gloria explained, “a very difficult experience that I was able to get out of. Successfully. Healed.” Long before Natalia and her brother were born, Gloria married young and willfully against her parents’ wishes; when Gloria discussed the eventual divorce with me, she described it as a period of hope and personal metamorphosis, an early heartbreak transposed into strength. She was, she said, “a fighter. Something that may be traumatic can become positive.” Natalia agreed, explaining, “I told her, there’s something that can be worked here, in terms of realigning your relationship to this moment that you might remember as traumatic.” With Gloria behind the camera and her past in front of her, she’s the artist, and history is malleable. Natalia-as-Gloria steps into a bathtub clothed in her wedding dress, as Gloria may have—or not—decades before. She laughs and cries: a euphoric release. Gloria has freed herself.

In 2016, they cowrote and shot the film in Miami, Florida. Natalia, who was living between Miami and Montreal, Canada, moved home after its completion to continue interviewing Gloria about “her process of aging, how she felt about the future, how she felt about the political situation in Puerto Rico.” In the current version of Retiro, these conversations, initially removed in the first cut, are everywhere, interlaced with scenes from Gloria’s short film and snippets from the editing process, including the opening scene’s crucially visible film crew. The unveiling of Retiro’s production renders the fable at its center uncanny—a nucleus nestled in its own creative deliberation, displayed across three simultaneous channels. “There’s some fiction,” Gloria added, referring to her imaginative choices for the script and her awareness that the woman in the film “is not me anymore.” The seemingly organic (sometimes arid) realism of documentary is inflected with the women’s meditations and the disclosure of their process. Together, they form a tender love letter from Natalia and Gloria to each other. No moment is presented without the mechanics or questions that shaped it: Gloria in the garden, florid flowers and rain-lashed tiles and her daughter’s subtitled queries in adjacent frames. Gloria afloat in the sea, astride shots of the shoreline and a small blazing sun, Natalia’s cues audible. The central periscopic performance features, in one frame, Natalia as young Gloria; in another is Gloria the director with headphones and a cigarette; and in a third, we see Natalia asking, in Spanish, “Why did you pick this moment?” It’s heart fluttering to peer behind the curtain.

“Retiro became a form of proximity, a way for us to come closer and dig deep in our collective and individual history,” Natalia said. “I didn’t know I was going to be holding so much space for her pain, even embodying it. That act of conscious surrender changed the way that I relate to her.” The film’s apparent layering permitted Gloria and Natalia to see themselves and each other: their shared creative agency, their reverence for their home, their unspooling of the past, and the intimacy of parsing it together. Gloria’s lyricism, Natalia’s insistence. Midway through the film, Gloria holds blush-pink roses at the cemetery, her words captioned in a bordering frame: “Your grandmother used to say she was waiting for her death. I’m not waiting for my death. I’m waiting for an evolution.” In another, Natalia asks, “Would you have liked your life to be different?” “Sometimes yes, sometimes no. Things happen.” Gloria enumerates her desires, how their urgency deepens with time: “I want to swim, lose weight, quit smoking. Enjoy life more. Get rid of these shadows that torment me.”

Over time, there’s a gentle but perceptible mood shift, particularly in footage shot after Hurricanes Irma and Maria in late 2017. “My mom told me there was a gap between the people we were then and now,” said Natalia, “filled with political revolutions, a pandemic, earthquakes, hurricanes.” In these later scenes, the pair travel through the fog of Borikén’s mountaintops, wade in its waters; Puerto Rico is the film’s third character. The two women transform into a kind of parabola, an intergenerational continuum of synchronous roles. Natalia instructs her mother, “Look at the sea.” They irritate each other. They grow closer.

This past summer and fall, Retiro was on view at Hidrante, a project space in San Juan, part of Natalia’s solo exhibition Libreto escrito, aún no existe (Written script, it does not exist yet)—the project’s first presentation in Puerto Rico. The film’s channels were projected onto three “screens”—vertical blinds, in front of windows—viewable from two rocking chairs, “the way it’s meant to be seen,” Natalia said. “You have to come to the space and make yourself available for it.” Hidrante’s space was once a home, and its former domesticity is palpable. In what felt like the dim evening quiet of a living room, a viewer’s eyes would’ve floated over the screens, absorbing Retiro incrementally. At the time of this writing, the exhibition is still on view with an upcoming component that, like the title, doesn’t exist yet. Gloria and Natalia are currently engaging in performative exercises, led by the latter’s cousin, Angel Blanco, a choreographer, dancer, and therapist. Angel is “extracting gestures from Gloria’s body language and creating a glossary,” which Natalia will memorize and somatically incorporate into balletic gestures. Natalia explained: “It’s an attempt to translate the filmmaking process into a live performance and shift the roles pre-established by the dynamic in Retiro,” with Natalia again becoming her mother, “beyond verbal dialogue.” This time, Gloria is not only director but also cinematographer, holding the camera and filming her daughter.

Near the screening room, Natalia deemed a section “Gloria’s Room”—officially titled Estamos desarmadas, meciéndonos en un columpio de ilusiones (“We are disarmed, rocking on a swing of illusions), a written observation by Gloria—decorated with furniture from her parents’ home and painted a warm, deep burgundy, like a gut. A 35mm slide projector shines images of archival materials onto the wall: photographs of an adolescent Gloria, Natalia’s fetal sonogram, Gloria’s illustrations and her footnotes scribbled across an early script of the film. Many of Gloria’s notes are lapidary; they possess a philosophical quality with their reflections on filmmaking and existence. “The awareness of what one has, of what the time of Retiro is, has changed,” reads one. Some allude to the psychogeographic terrain of Borikén: “…Maps, of the Caribbean region, with all the underground geological faults, that raise us again and make us remember that we are very vulnerable.” It seems Gloria has divulged her heart on paper, though we might just be reading her poetry: “Here we meet, facing the fiction we’ve created of our lives.” Her words impart a written archive, to rhyme with Retiro’s cinematic one, of mother, daughter, and the archipelago of Puerto Rico, itself a matriarch. One reads like a melody: “Because we all change / in the course of time / and we incorporate into our life / irrelevant things that mark us / but there are other things that remain essential / which go to the core of who you really are.” As the title credits roll, the coquis’ nocturnal song resurfaces, recalling a tender maternal tradition: a lullaby.

Image Credits:

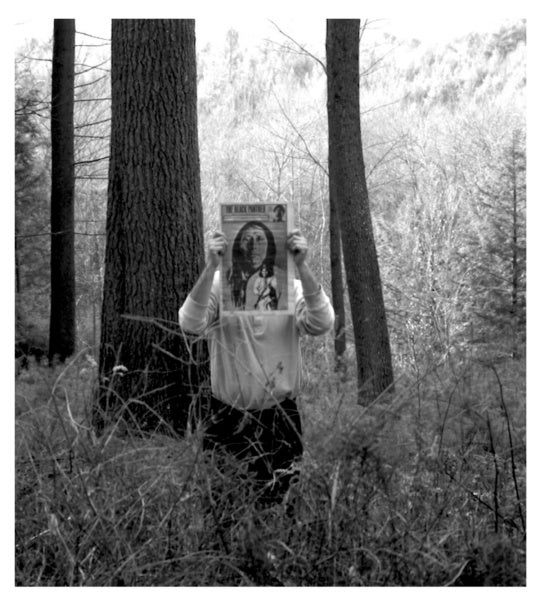

Natalia embodies Gloria in Gloria’s film, 2016, directed by Gloria. Credit: Diana Larrea

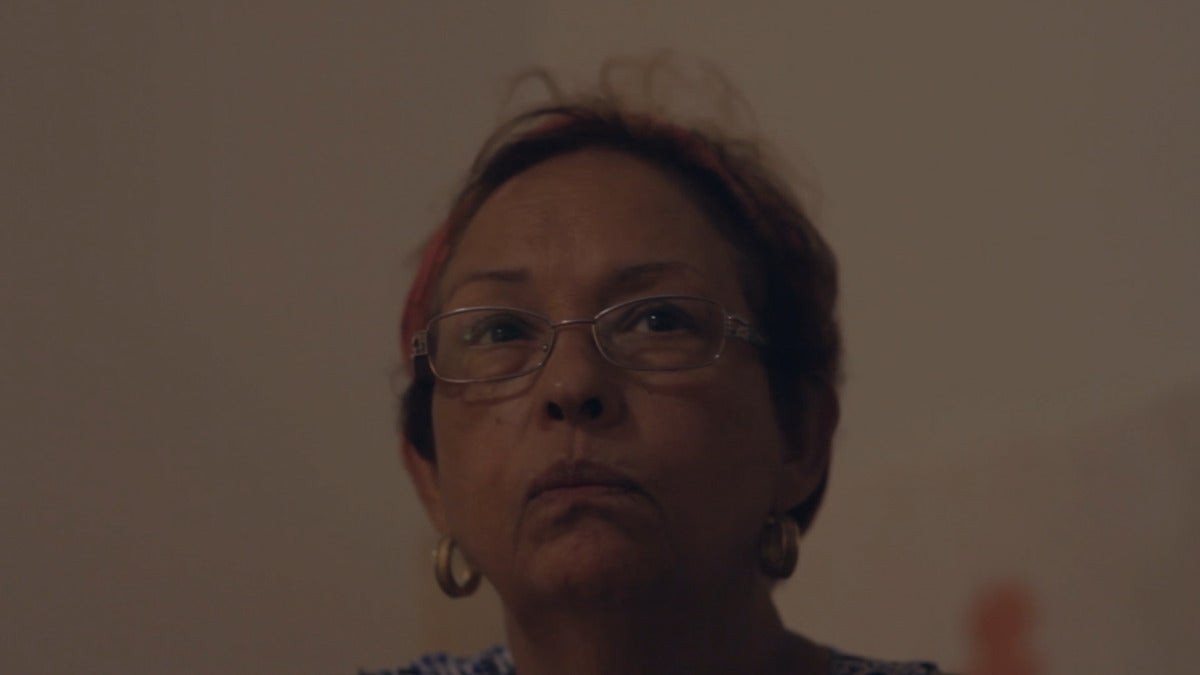

Gloria watching Natalia embody her reconstruction of her past, 2016. Credit: Terence Price III

Gloria tending to her garden in her house in Bayamón, Puerto Rico, 2017. Credit: Natalia Lassalle-Morillo

Natalia and Gloria rehearse in Gloria’s home, 2021. Photo Credit: Christopher Gregory

This was originally published in our 2021 Reader, Treasure.

This essay was part of Burnaway’s yearlong series Belief and Fiction.