Marquetta Johnson’s legacy is much like her quilts: rich, connective, experimental, traditional, emotional, and withstanding. As a teaching artist and fine artist, her practices were steeped in her jovial passion for life and resolve that teaching young artists can change the world. Her legacy is: drawing people together through the art of quilting, inspiring fresh and new ways of being an artist, and using kindness and generosity as an art practice in and of itself.

Any limits placed on her as a quilter, she surpassed. A student of the craft, she respected and honored the tradition and art of quilting but was also known to experiment fearlessly with fabrics, shapes, and approaches.

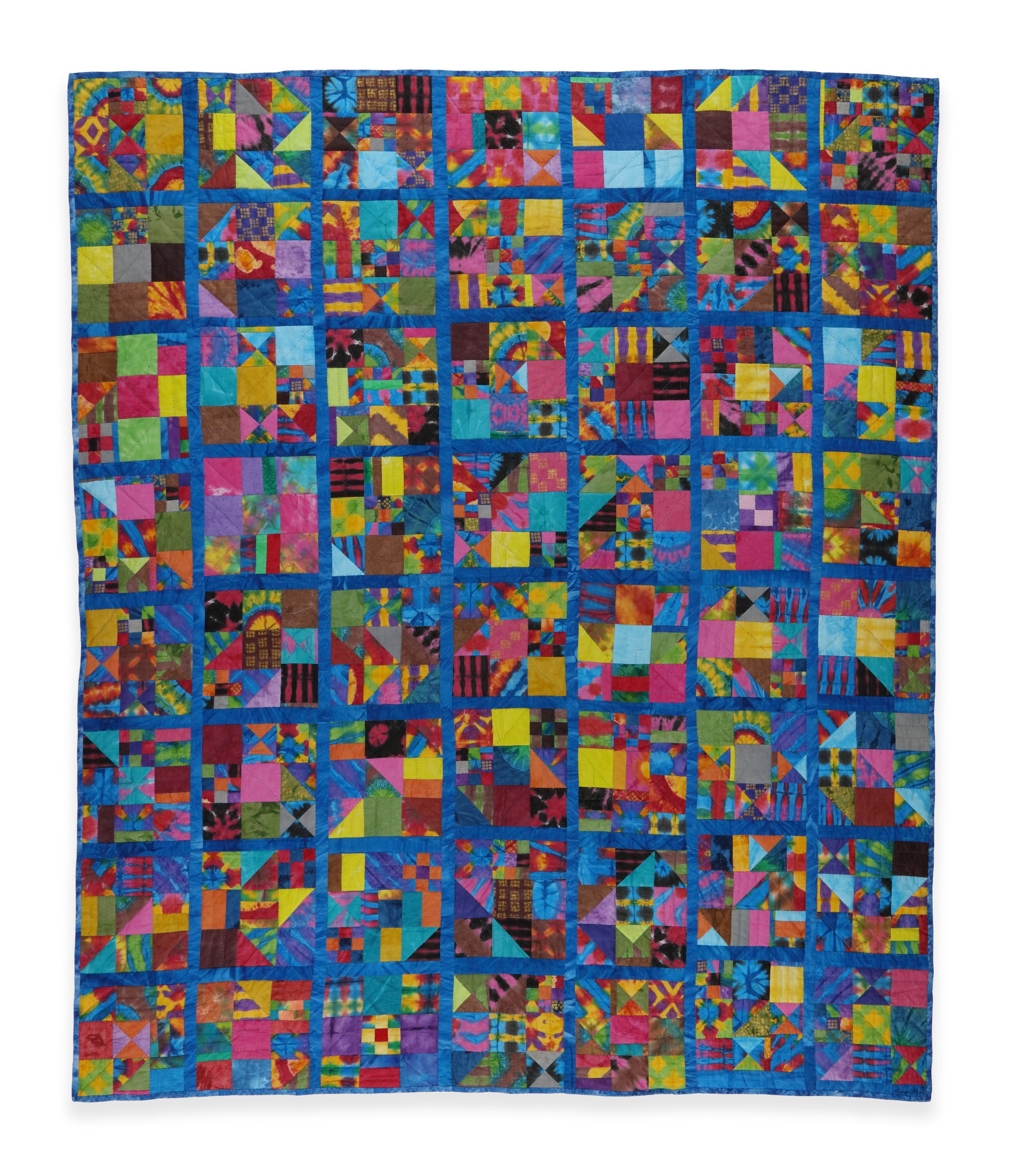

Nine Patch, completed in 2018, is a nine foot by seven and half foot display of neat, orderly squares made up of nine smaller, hand-dyed or painted squares. It is emotive, unyielding, expressive, and loud, using pattern in a way that both honors the precision of a traditional quilt pattern while still overflowing with novelty and movement. Some pieces of fabric are repeated, others are not. Reds, blues, pinks, oranges, and yellows placed together so tenderly, it feels both playful and gentle, yet somehow a bit somber too.

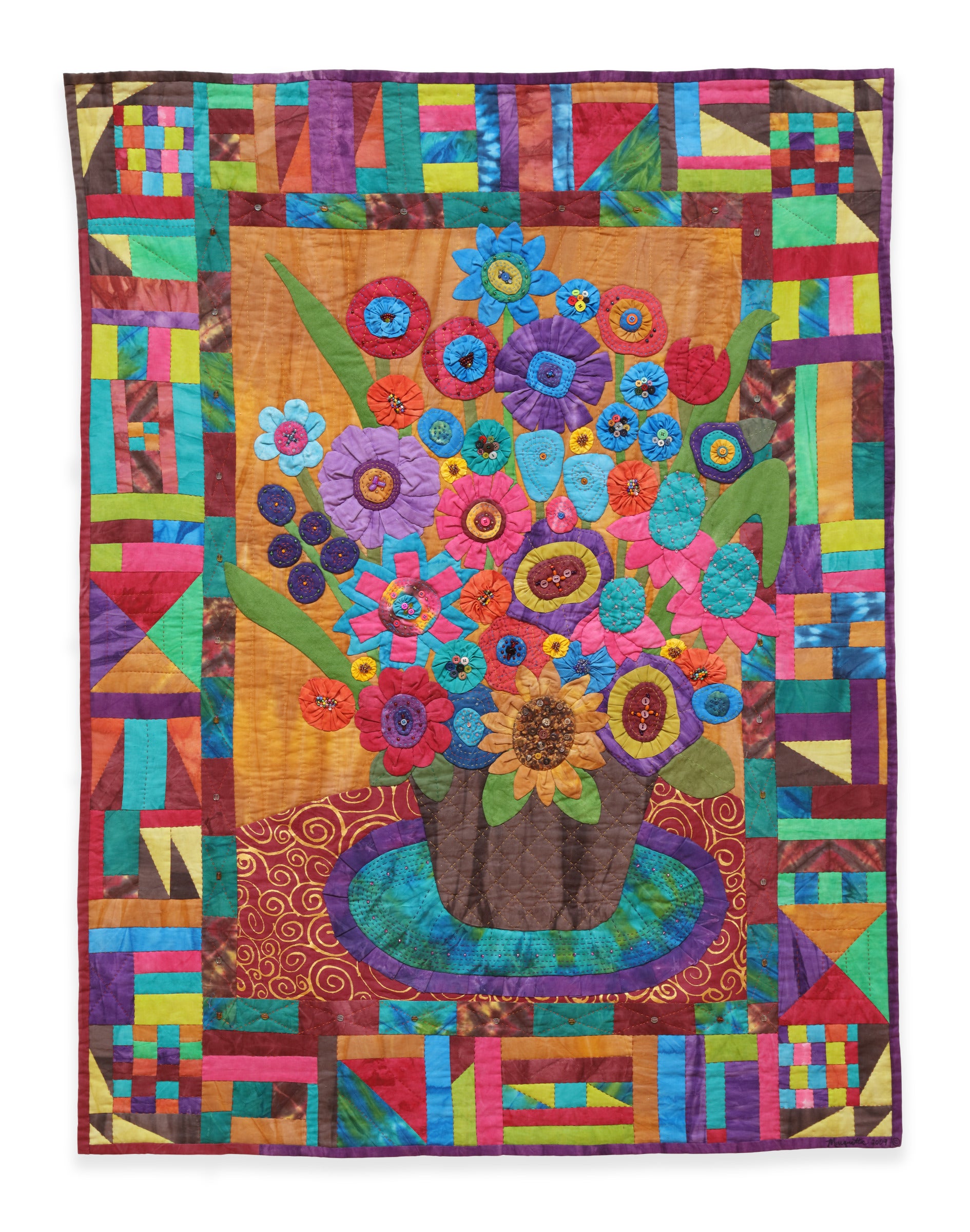

She continues in the playful, gentleness with the even more expressive Hope Blossoms, completed in 2009. Surrounded by a border of square patches, is an explosion of color in the form of a bouquet with about two dozen flowers of a wide variety stitched into the very center of the quilt. The flowers rest in a vase of water, of course, atop a burgundy surface adorned with gold spirals extending in every direction. Like Nine Patch, the fabrics used are also hand-dyed and hand-painted, with buttons and beads, all placed in a unique, but sensible arrangement.

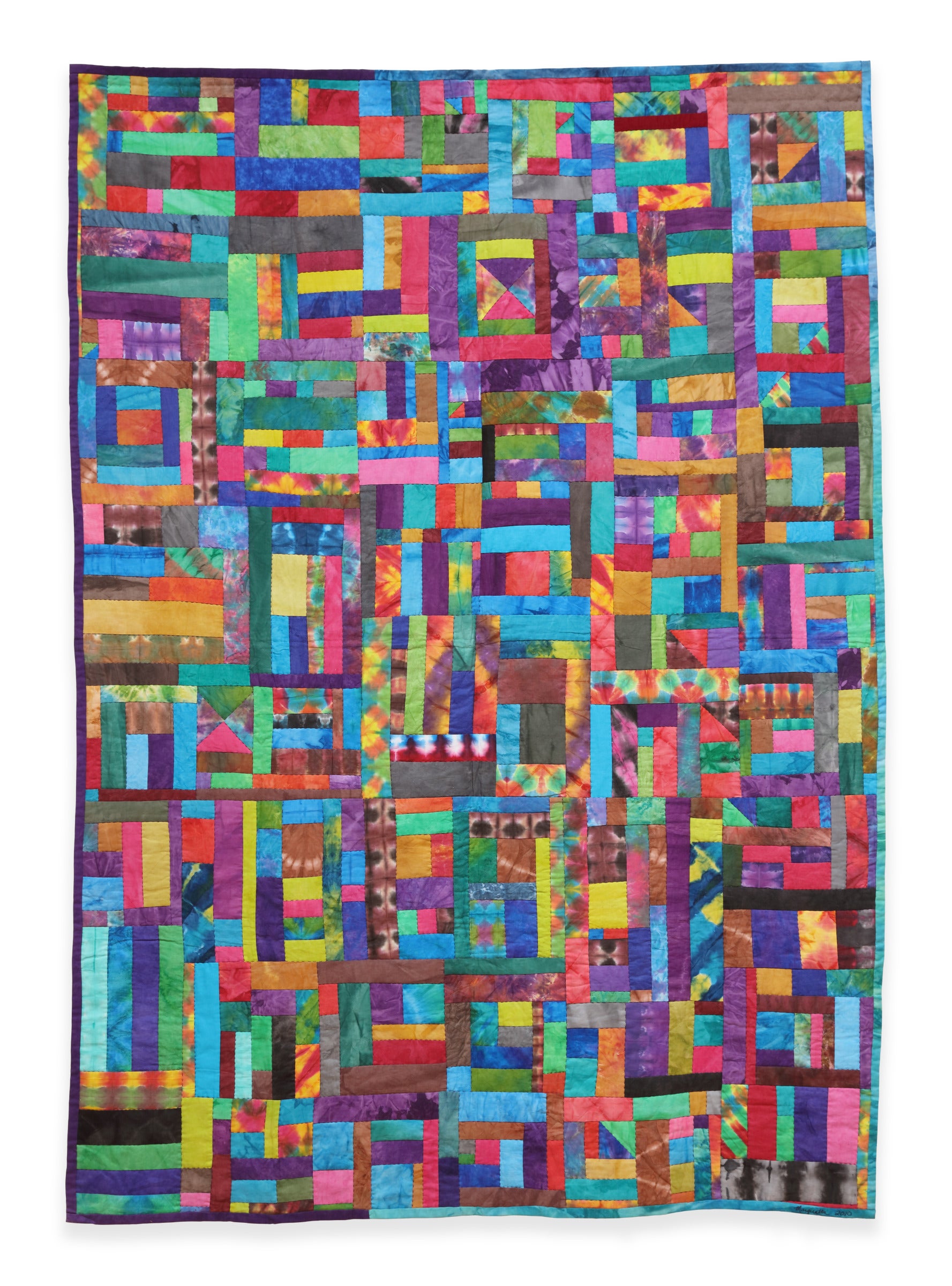

She compared her practice to jazz.1 An example, Small Steps (2017), calls to mind John Coltrane’s 1960 record Giant Steps in the improvisational, roaming style that tightly binds together the “standards” of the craft while bending them to the will and flow of the artist. The quilt truly is a series of small steps bumping and nudging against each other in a flowing arrangement of color, direction, pattern, and length. Each piece of fabric boldly calls back to another, like a visual reprise of a part tactfully added elsewhere, yet still somehow remaining in tactile tune with each other, never feeling overwhelming or disconnected. One of her jazziest works, indeed.

As an artist who learned to quilt from her grandmother, Hattie Miles, Johnson was a part of a longstanding artistic legacy that is still felt and seen in her students. Yet, even as a quilter with a medium rich in literal patterns and techniques, she offered a spirited, charismatic, and experimental approach to her work that faithfully reflected her approach to life.

It was for others, too, she broke down barriers and gracefully blurred the lines between teaching artist and fine artist. She stepped out of her own comfort zone and crossed the boundary between these two worlds to show others, especially her young artists, that any box that attempts to define what kind of artist one can become is optional.

Her students and participants made great progress as a result of her willingness to push them and push herself out of what is easy, typical, or expected. She left rooms, people, and groups better because she never shied away from spontaneity or doing something new.

Whether it was an apprehensive principal who wasn’t convinced their school needed to invest in teaching artists or a hardened student who wasn’t trusting of adults, let alone strangers, Johnson was known to win over a room with an energy of pure conviction. She called her students “young artists,” regardless of how much experience they had or how old they were, perhaps to invite them to feel confident enough to stretch the boundaries of a medium and their own imaginations. Generosity was her practice. Giving without hesitation, brimming with creativity and ideas, even calling her collaborator, Jeff Mather, at 7 AM to talk about plans. She started her days filled with excitement and desire to create not for personal gain, but for the benefit of others.

Any limits placed on her as a quilter, she surpassed. A student of the craft, she respected and honored the tradition and art of quilting but was also known to experiment fearlessly with fabrics, shapes, and approaches.

Alongside experimentation, her legacy also holds a childlike zeal that she had for life and the beauty she found in it. Once in Utah she insisted on driving south, because she learned there is the least light pollution there in the country. Upon arrival, she marveled from the car window, celebrating the patterns in the sky that she couldn’t see from Atlanta and gleefully calling them out one by one.

She was committed, working to the very end of her life to get her quilts into different exhibitions and projects. She wanted her work to continue to be shared, even after she was gone. Not wasting a moment, relentlessly extending beyond herself. Generosity even in death, she gives and teaches still. And her young artists—anyone who engages with her work—are better for it.

Johnson died on February 11, 2025 and now rests at the Salaam Memorial Cemetery in Atlanta, GA. She was sixty-nine years old. Her funeral program is deep purple with a thin white border. On the cover, she too is dressed in purple, smiling softly in front of a quilt. It is filled with prayers, two photos, the order of service, and her six-paragraph obituary. It concludes with the poem “She is Gone” by David Harkins, encouraging those who knew her to “love and go on.”

[1] Isadora Pennington, “A Stitch in Time: Artist Marquetta Johnson shares legacy of quilting with new generation,” RoughDraft Atlanta, July 15, 2021, https://roughdraftatlanta.com/2021/07/15/a-stitch-in-time-artist-marquetta-johnson-shares-legacy-of-quilting-with-new-generation/

This essay was published thanks to support from the City of Atlanta Mayor’s Office of Cultural Affairs Municipal Support for the Arts program.