In this letter, SHRINE founder and director Scott Ogden responds to Madeleine Seidel’s review of Mary T. Smith’s exhibition I WE OUR at his gallery, originally published on June 27, 2019.

Art historians have long grappled with the question of whether an artwork should be evaluated based on its merits—or lack thereof—or on its maker’s biography and background. There is no easy answer to this question, particularly when discussing artists who are self-taught, many of who live(d) in quite unique circumstances or conditions. Departing from stringent and sometimes polarizing art historical views on this subject, most of today’s critics and art writers take a more nuanced approach that includes both a discussion on the work of art itself as well as consideration for the artist’s history and what influenced their creations.

In her recent review of Mary T. Smith: I WE OUR at my gallery SHRINE, Burnaway contributor Madeline Seidel’s foremost and defining critique of this show is: “You should know that Mary T. Smith displayed her art in her yard, but there is no indication of this anywhere in Smith’s exhibition I WE OUR (…) at SHRINE.” This is simply not true or accurate. Seidel also admonishes the lack of wall texts, labels or biographical information in the exhibition, while at the same time making note this is very typical of most gallery presentations.

You should know that I am very aware Mary Tillman Smith’s paintings were displayed outdoors, and the decision to display these works on white walls and without texts was intentional. The exhibition’s press release, which is available both online and as a printed take-away near my front desk, clearly relays, “These paintings, which were displayed outdoors and obviously made to be seen and attract notice, fall neatly into the tradition in the Deep South of the United States of ‘yard shows’ created by African Americans on their properties to commemorate personal histories, or to allude to certain thoughts, beliefs, or social-political messages that cannot always be openly expressed.” The press release also provides basic historical background information on Smith and further descriptions about the original context of her artwork. These paintings also speak for themselves and bear the scars and wear-and-tear of having lived outdoors in her yard for many years. As a direct nod and subtle homage to Smith’s environment, a group of six irregular paintings on found sheet metal are installed together in a constellation that references her own yard arrangements without having to spell it out for viewers directly. Employing sod, yard plants, or even text and wall labels around her paintings would have immediately diminished the power and resonance of the individual artworks in the show, and it would have instantly altered viewers’ opinions of the paintings before they had had time to take them in as works of art.

I believe truly memorable and important works of art must be able to stand on their own, without knowledge of the artist’s biography or intentions to lean on. Is it helpful to know that scarecrows made by Hawkins Bolden were created by a blind maker? Yes, of course it is, but this alone is not enough to qualify them as strong art, and this fact should not immediately alter how we first perceive his creations. Bolden’s history and visual disability inform his work, but they do not define it.

As a great admirer of Mary T. Smith and her artwork, I have researched her along with many other self-taught artists for more than twenty-five years. When opening I WE OUR, I wanted to ensure that Mary T. Smith’s work was given its proper due on its own terms, and I wanted to display it with all the grandeur and reverence it deserves. As Seidel points out, Mary’s joy is something you can’t help but feel when you look at her paintings. Seidel, however, opts to chronicle the hardships Smith faced as a Black woman artist in the rural American South as opposed to the empowerment she garnered from creating her paintings and the sense of self-worth this pursuit surely gave her. You can feel her presence while looking at these paintings, even if you cannot directly identify her in the images or lack a full understanding of her life story and situation.

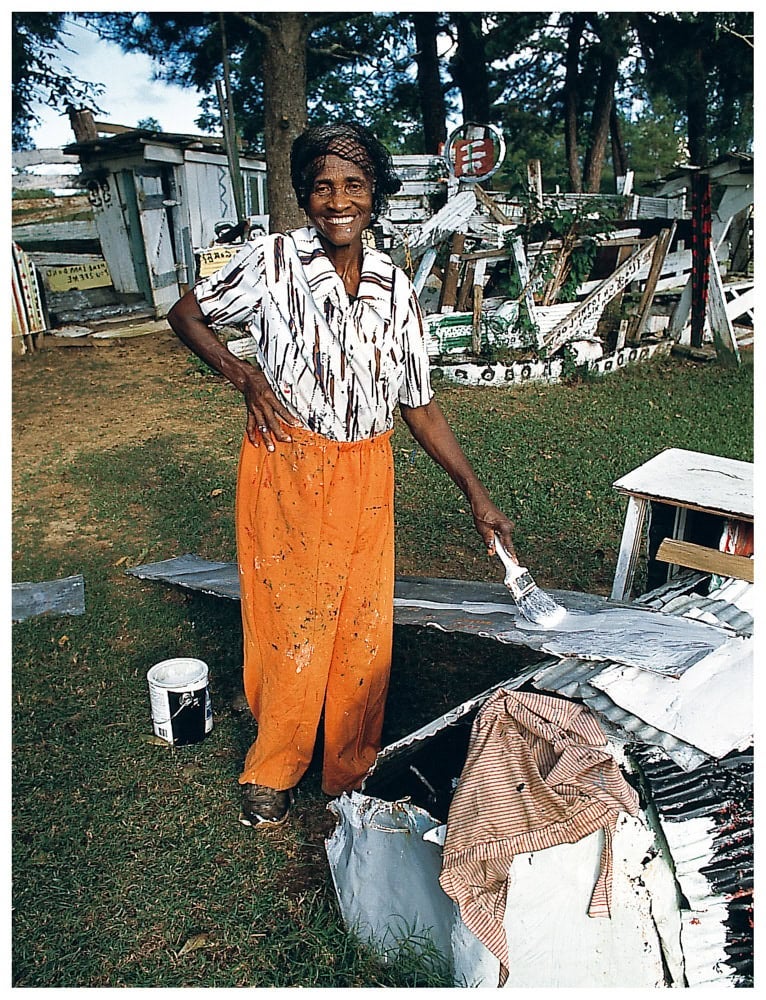

In her review, Seidel uses the word “anonymizing” to describe how the lack of historical context in this exhibition will bury Mary T. Smith’s name and history, and she uses the words fetishization and misrepresentation to describe the show’s “neglect of (her) personal struggles.” These sentiments are antiquated in terms of how museums and galleries have recently chosen to exhibit works by self-taught artists. An opposite effect actually happens when we follow Seidel’s suggestion of placing biography front and center alongside works of art: the artists and artworks become deeply fetishized the more remarkable the biography of an artist is, and this narrative effect tends to keep these artists relegated to the outskirts of “folk” and “outsider” art instead of being brought into the larger world of contemporary art. Even more troublingly, Seidel labels Mary T. Smith’s paintings as folk art more than once in her writing. This label haunts the field of self-taught art and particularly denigrates the wildly innovative and experimental nature of artwork created by Southern African American artists. It is obviously deeply troubling that an artist like Mary T. Smith passed away with little to no money and that she certainly must have experienced profound racism during the course of her life, but highlighting this over the joy she so obviously took in creating art is not a service to her artistic and personal legacy. To see images of Smith in her yard creating art makes it very clear that painting brought her intense happiness, purpose, and a powerful voice to communicate with the world around her—despite poverty, racism and hearing loss, not because of it. I WE OUR is a solo exhibition of works by Mary T. Smith in New York City; this is the complete opposite of an anonymous presentation.

Learning more about Mary T. Smith and the life she lived definitely adds an important layer of appreciation to her work, but it is also a profound and incredibly meaningful experience to view her paintings on their own terms, without any forced concepts or notions of what we think she was attempting to convey. The artist is not here to guide us directly, so I think it best to be extremely thoughtful while attempting to decode and interpret what she has left behind.

Mary T. Smith: I WE OUR is on view at SHRINE in New York through July 28.