“She knew you would come when we called you in her name,” said Michelle Lanier in her steady voice ringing with clarity and urgency, of formerly enslaved autobiographer and abolitionist Harriet Jacobs, to the sixty or more Black women who dined together that night in Raleigh, North Carolina.

It was Thursday, March 21, 2024, just days after spring’s arrival, and most of us traveled that day from elsewhere to participate. An hour or so into the dinner, Lanier, director of the Harriet Jacobs Project and North Carolina Historic Sites, and Johnica Rivers stood together at the center of the room. They announced the emergence of Rivers as Curator-at-Large of the Project, and of all of us as a dawning collective, gathered across generations to witness the enduring life of Jacobs by dwelling in the “land that saw it all,” to therefore realize our own possibilities. In the gravitational pull of the duo’s presence, many of us arose and moved toward them.

The inaugural Sojourn would unfold across three days, carved by the meticulous hands of Rivers and Lanier. They would take us to the land and waters of Edenton, North Carolina where Jacobs was born. We would touch the place where she disappeared from enslavers for seven years in her grandmother’s nine-foot by seven-foot garret, where she bore a miniscule “loophole” in that place’s wall to see and breathe with the gimlet her uncle made, where she escaped by way of the Chowan River that carried her north, where her family lie buried on a hill. We would move through the 1767 Chowan County Courthouse, recast by Southern American artist Letitita Huckaby’s site-responsive installation for the Harriet Jacobs Project. We would weep, we would sing hymns, we would dance. We would meet and engage in conversation with each other, and—perhaps unknowingly—behold the God that Jacobs wrote about, her guide and salvation. We thereby had the opportunity to redefine the terms of our freedom at such a time when ourselves and our world so desperately need it.

Camille Bacon, Daria Simone Harper, and I all sojourned together. Before we even left we longed to return to that place, both geographically and spiritually. And so this conversation is an attempt and an invitation to linger there. This is also an attempt to hold our overwhelming gratitude for Johnica and Michelle whose gracious determination brought us to Sojourn, creating another “loophole of retreat.”[1] We are honored and transformed by your love, and that of our fellow sojourners—those who were there physically and beyond. Unlike a traditional interview, I gave Camille and Daria a few prompts that they responded to in conversation together below. The following conversation was edited for length and publication. Here we endeavor not to capture but to open a portal.

“We love you. Even those who we are just meeting,” continued Lanier in her remarks. I can’t help but feel that we are at the cusp of a movement. Harriet Jacobs Project beckons: “Let us draw nigh.”

—Niara Simone Hightower

“The dream of my life is not yet realized” – Harriet Jacobs

NIARA SIMONE HIGHTOWER: First I would love you both to describe your arrival to Sojourn.

CAMILLE BACON: The first person I saw upon arriving was Michelle Lanier. I immediately noticed she had triangular parts in her box-braids as a devotional nod to the garret that Harriet Jacobs hid in, i.e. the architectonic geometry of Harriet’s escape was etched all over Michelle’s scalp. What a wonder, from the very first second!

We embraced and she looked at me in the way Michelle does–with that permeating regard that makes you melt more deeply into yourself–and she was like you know, Camille, we knew that Harriet was going to make sure you were here. Otherworldly forces were at play, orchestrating a togetherness that felt like it was millennia in the making.

Having this conversation is a really vast and welcome challenge because I don’t really know how to thank someone, how to thank Johnica, how to thank Michelle, how to thank Harriet, for breath itself.

DARIA SIMONE HARPER: I love that expression: How do you thank someone for breath itself? There was such an exchange of breath and such life poured into one another over the course of those days that each of us so clearly needed but hadn’t even recognized before we arrived. It felt incredibly prophetic that Michelle and Johnica would place us all in communion with one another in that specific time and place.

NSH: How did you feel leading up to Sojourn, how did you feel during, after?

CB: The gathering came at a time when it felt like the walls were closing in. I remember feeling this brittle lightning around my body and I was questioning whether or not I “deserved” to be in North Carolina when we had so much work to attend to. We were in the final stages of bringing our second issue of Jupiter across the horizon and we were juggling a cascade of new responsibilities that we were (and are) still learning to stretch into. I wasn’t sure how I’d be able to put all that down to make way for the modes of being that Sojourn necessitated. At the same time, attending felt like an urgent biological need I couldn’t turn away from.

Sojourn was special in part because we were not expected to produce anything. We were only expected to be there and to be together. That was the only mandate. It was overwhelmingly reorienting to be received in a language of care that did not depend on our being taken or extracted from.

DSH: My expectations were shattered in the most profound way possible. In the days leading up to the Sojourn, life was swirling and I felt a bit spread thin on the physical register.

From the moment I stepped foot onto the hotel grounds and began encountering other guests of the Sojourn, it was as though my nervous system was being recalibrated. I felt held in a very specific way, which was so welcome given the nature of our convening.

As Camille mentioned, it certainly was not all joyous. We were reckoning with and holding space for so much. We shared collective grief and all kind of came undone, before helping each other to put the pieces back together.

Leaving North Carolina I felt totally washed anew, baptized in a way. There was this beautiful reflection that fellow Sojourner Virginia Cumberbatch shared of her time, which is that this gathering seemed to grant so many of us with a permission that we didn’t realize we were in need of. I walked away feeling a renewed sense of this fire which I’m not only allowed to move through this existence with but destined to.

CB: The “granting of permission” that took place was so crucial because it reminded me that while we have a responsibility to do right by our commitments, we also have a responsibility to find our clearings, to enact respite as often as we can.

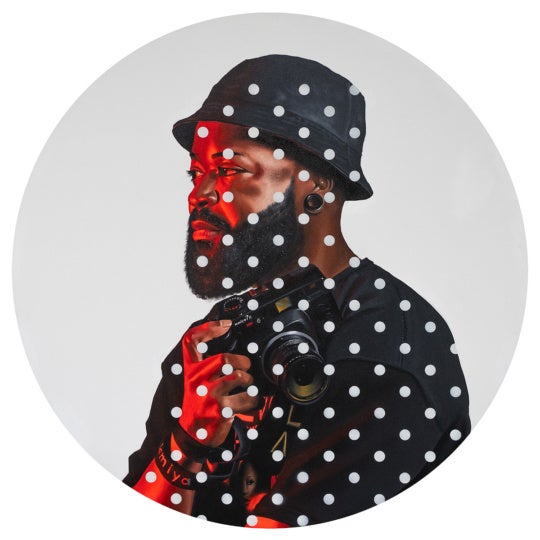

Edenton, North Carolina. Photo by Victoria Louisa Sanders and courtesy of The Harriet Jacobs Project.

NSH: “skin to soil”

“It is not enough to read the book,

It is not enough to go into the archive,

You need to go to the place.”

—Johnica Rivers at Sojourn

DSH: Johnica gifted us with this gem during her remarks at dinner on the first night of Sojourn. As we arrived in Edenton at the grave site of Harriet Jacobs’s family, the Horniblows, there was a strike through time and space that seemed to alter each of us on a chemical level.

I recall this specific moment when we each gathered white flower petals from a large basket that Michelle held. We all moved together toward this body of water which carried Harriet to freedom, to spread our offerings along the water’s edge. In that instant, I felt the massive presence of all the ancestors and guides I carry with me every day, including Harriet, speaking with such clarity.

I was so moved by the force of our collective spirit. We were able to hold and hold space for one another in a way that was so massive. There may have been some seventy of us there physically, but it felt as if there were thousands of us there in spirit to honor Harriet’s legacy.

When I sit with this notion of putting skin to soil and moving outside of the text, outside of the archive, I’m reminded of the real spiritual residue that exists within an environment, and particularly within our sacred sites. Within the soil, the water, the flora and fauna…there’s so much life there. Simultaneously, there’s such tremendous joy and pain there. In the spirit of vanessa german, we experienced the fullness of grief and love and grief and love at the same time.

CB: The notion of putting “skin to soil” recalls that this was a pilgrimage of sorts. You used the words “communion” and “baptized” earlier and there was indeed something deeply theological about it all. It felt like an initiation. Like we were meeting God more deeply with every breath. I came apart at the seams; I think we all came apart at the seams.

I have never participated in a ritual with that many people before and our ceremonies were a reminder that study is not only what you do at your desk in solitude, surrounded by your books. Study is also what you do when you hold hands and walk towards the water in silence with an unspoken and shared promise of what you’re about to do together.

The memory of offering white rose petals to the river all together–to the exact water that carried Harriet to freedom–is etched onto my insides forever. To hear ripples of Harriet’s voice alongside the voices of my own ancestors, to feel the vastness of that support is something that defies language entirely. But what I will say is this: I didn’t know that there was that much love available to me. I didn’t know how easy it was to reach for it until Sojourn.

Our journey to Edenton reminded me of all the places that wisdom has always lived for us. It reminded me of how deeply I have neglected the magic and mystery of the wisdom of my body and spirit. In the same stroke, it reminded me of how deeply I have also neglected the wisdom in the bodies and spirits of all those I love, both enfleshed and otherwise, and I felt urged to act otherwise. It reminded me, too, of the grief that comes with understanding the scale of the forces that seek to forebode our recognition of that wisdom. Our rituals allowed me to touch the hot core of that grief, and then to be rocked back into a cradle of sublime levity. I sensed our boundlessness on a cellular level. It was catalytic. Yes, Sojourn was catalytic.

I also feel like we made a tear in the timespace continuum. I have this sense, still, that in being together for three full days, we built another place that we now get to draw wisdom from in order to continue revising the realities we inhabit. We made another place by going back to the place. In an oblique way, that makes me think about the fact that Harriet was operating in two different dimensions at once, in a sort of simultaneity of time wherein she knew she was free while also being wrapped up in a material reality that sought to pillage that sovereign self-relation. She reminds us that our freedom dreams are bound up with this necessity to actually project ourselves beyond the reality that we’re living in to then write it anew.

NSH: what is not free? / (re)defining freedom / on refusal

“You are an emergent emergency.”

“You are a danger to what is not free.”

—Michelle Lanier at Sojourn

CB: There are two sentences from Michelle’s remarks that shifted the tectonic plates of my being. “You are a danger to what is not free. You are a danger to what is not love.” I have incanted these phrases every morning since we got back from North Carolina, and each time I do, it feels like I’m striking a match of possibility within myself. I aspire to do justice to those words; I aspire to embody their world-bending and insurgent implications. They became the thing that I brought home with me to carry forth the enchantment of Sojourn even after and from afar.

Through Michelle’s remarks and my meditations around them, I now also understand Harriet’s conception of her own freedom as something that existed out of the bounds of the rhetoric of a legally and culturally entrenched system constructed to negate her aliveness. She says, for example: “It seemed not only hard, but unjust, to pay for myself. I could not possibly regard myself as a piece of property…I knew the law would decide that I was [Dr. Flint’s] property…but I regarded such laws as the regulations of robbers, who had no rights that I was bound to respect.”

Her disobedience to “the regulations of robbers” indicates that she understood her aliveness under an alternative rubric that, in “not possibly regard[ing] [her]self as property,” jeopardized the ideological register at which the system of slavery justified itself. So, part of why that incantation of “you are a danger to what is not free” and “you are a danger to what is not love” feels so galactically enthralling is because there are other possibilities that suddenly emerge when we understand that we’re already sovereign and that we can, like Harriet, rebuke the antebellum vocabularies that seek to grind our self-possession down to dust. She made herself otherwise, and we can do the same.

Harriet also says in a letter to Amy Post, which appears in the appendix of the book, that: “I thank you for your kind expressions in regard to my freedom; but the freedom I had before the money was paid was dearer to me. God gave me that freedom.” She knew from a God beyond herself that neither she nor her freedom was a commodity. Her freedom was not something that could be bought or sold because for her to acknowledge her life and freedom in a market context would be to betray the fundamental underpinnings of her inherent sovereignty.

Based on that other way of knowing what a life can be and how not to betray it, she rewrote her self-hood in excess of the law. And so, of course, Harriet was “a danger to what is not free” and “a danger to what is not love” too.

DSH: It’s been such a blessing to continue returning to this language: “You are a danger to what is not free.” You mentioned the word galactic a moment ago, and I think that is perhaps one of the best lenses through which we can frame things. The very nature of Harriet’s understanding of the machine of slavery and how it functioned, it shattered everything, especially in that time and place.

With all of the tools that she possessed, Harriet was committed and dedicated to asserting this truth about her own sovereignty. She was thinking and visioning in a way that was so cosmically, infinitely ahead of what everything around her said was possible. For her to not only possess this knowledge, but to continue asserting it is so profound. For me, it sparks this deeply existential thread about the responsibility that comes along with this knowledge, especially as I reflect on all that Harriet was capable of.

Each of us left our time in Edenton feeling totally and forever changed by what we experienced collectively. Realities were seismically altered. The visionary that Harriet was reminds us all of the spirit that we must carry on with throughout this existence. I’m so deeply honored to have convened and to have held that sacred space.

CB: One of the last things Harriet writes in the odyssey that is Incidents is “the dream of my life is not yet realized.” She lived in the subjunctive tense. Her story spills over and there’s so much more to speculate around, still.

I still want to muse more about her smirk as a gesture, as a precise way of marking a density of feeling and knowing. A smirk is neither a full smile, nor is it a neutral expression. It’s latent and thrumming and full of activity. When I close-read her portrait, I sense that smirk as a kind of emotive punctuation and a signifier of her propensity for life-extending disobedience.

I still want to deepen my thinking about Harriet alongside the tradition of minimalism, especially when we consider her negotiations with the triangle of the garret, the rectangle of the loophole and the point and curvature of the gimlet. To that end, I still want to talk about the contemporary reverberations of her legacy through the work of artists like Zenobia, Ben Giska, and Torkwase Dyson, all of whom carry forth her brilliance through relative degrees of abstraction.

I still want to talk more about the ambivalence of the form through which her story is told and the fact that abolitionists were involved in its publication, which likely means the fullness of her expressions were mediated and therefore reduced by at least one degree.

I still want to consider the metaphysical conspiracy of it all, the fact that this is a woman who was collaborating with the Divine and the people in her community to fundamentally restructure the fabric of American society, to usurp the prisms through which we regard humanity and collective responsibility.

In the spirit of Harriet and Johnica and Michelle and all those we Sojourned with, we keep garnering our gimlets, lingering in the loophole, and rebuking all freedoms that come tethered to contingencies.

“What I want to say even more is this

There is another danger

And that danger is

You.”—Michelle Lanier at Sojourn

A Sojourn for Harriet Jacobs in Edenton, North Carolina, was organized by Johnica Rivers, Curator-at-Large of the Harriet Jacobs Project, and Michelle Lanier, Director of the Harriet Jacobs Project and North Carolina Historic Sites.

Letitia Huckaby’s Memorable Proof will be on view at the 1767 Chowan County Courthouse through August 31 before traveling to the Center for the Study of the American South at UNC-Chapel Hill, where it will remain on view through the end of the year.

[1] “The Loophole of Retreat” is the title of Chapter 21 in Harriet Jacobs (1813–1897)’s Incidents in the Life of A Slave Girl. It was also the namesake for Loophole of Retreat: Venice (2022), a symposium organized by Rashida Bumbray with curatorial advisors Saidiya Hartman and Tina Campt for Simone Leigh’s exhibition at the U.S. Pavilion.