Back in January 2015, we visited Gwen and Larry Walker in their home in Lithonia, Georgia. The Walker home is a multi-faceted dwelling. While certainly “home,” it also houses their art collection, including works by Gwen and their daughter Kara along with numerous local artists, along with treasured memorabilia and Larry’s spacious studio. Over a light lunch they had graciously prepared, the Walkers reminisced about their early days and talked about how they ended up in Atlanta.

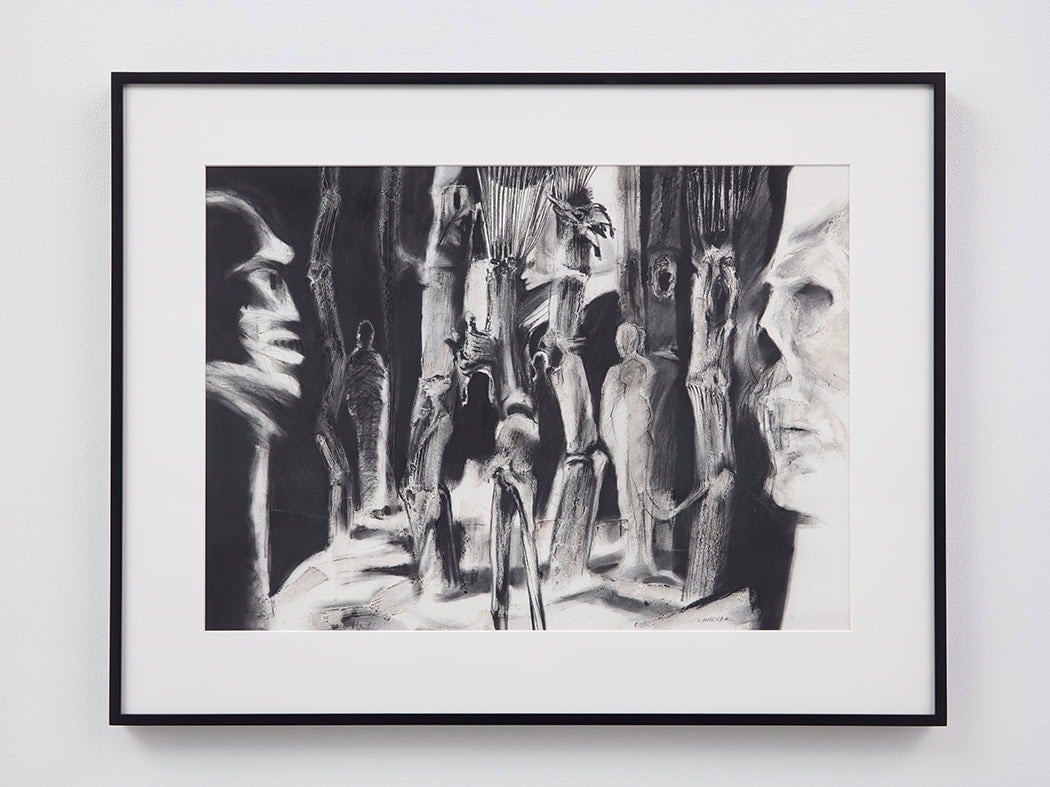

Earlier this summer, Larry had an exhibition (curated by Kara Walker) at Sikkema Jenkins in New York, which was favorably reviewed by Artforum. Another show, “Selected Works by Larry Walker,” just opened at the Welch Galleries at Georgia State University and will remain on view through November 11 (a reception for the artist will be held on September 8).

This Saturday, Atlanta Contemporary will honor Walker as its 2016 Nexus Award Winner. At 80, Larry Walker is hitting his stride.

STEPHANIE CASH: Did you return to Georgia for a job or because you had family here?

LW: It was because of the job. I also moved to California for a job. When I moved to Detroit, that was a different situation. My first college teaching job was in California. Well, let me start from the beginning. I graduated from the High School of Music and Art in New York City, and I had no idea what I was going to do next. People said, “What are you going to do? Are you going to college?” I figured, you know, maybe I’ll go to college for a little communion, maybe I’ll join the service for a little bit, maybe I’ll keep working in the supermarket—I don’t know.

Meanwhile, my mother, who was ill, went to Detroit because my oldest brother lived there. He felt that he could take the best care of her, better than any of the rest of us — I’m the youngest of eleven. My father died when I was six months old and my mother never remarried. As the kids grew up, they dispersed here and there. They wanted me to come to Detroit, too. They were worried about me because I was the youngest. They said, come here and you can go to Wayne State University. That summer, I moved to Detroit and got a job at A&P supermarket. At the end of the summer I said, “Okay, I’m ready to go to school now.” Since I didn’t have my transcript or any application paperwork, I had to take an entrance exam, and I didn’t pass. So I went to the community college and transferred into WSU after a year. I eventually graduated from WSU and then went back for my Masters. Between all that stuff, Gwen and I met and got married.

Gwen Walker: Growing up in Detroit, and living in various places, my mother wanted to be sure that I went to the right high school. I’m a daydreamer, and my mother didn’t know what to make of me. So I went to the High School of Commerce, which was the type of education I needed, because one thing I hated was sitting in the classroom listening to someone talk. And so at Commerce, of course, you’re always doing something: typing, shorthand, all that good stuff. Halfway through the program, you get a job. So it was neat working four hours a day and making money and going to school. Eventually, I went to WSU. I was working full time, so I was only going to school at night. I met Larry in the supermarket. In high school, during my senior year, I stopped in the store and I was wearing my high school beanie. This tall guy was stocking cans and he asked me about the beanie and I thought, “Hmm… He meets the first qualification: he’s tall.” But I stopped going to the store and that was it.

LW: Yes, she stopped going to the store. Her mother would still come in, and one day I asked her, “Where’s your daughter? Did she get married?” She said, “No, she didn’t get married.” So of course her mother went home and said, “He asked about you!” So she magically appeared again!

GW: I had the world’s worst cold! My eyes were red. My nose was runny. He asked for my phone number as he was checking out my groceries. So I gave him my phone number.

LW: After finishing my undergraduate degree I was an elementary school art teacher in the Detroit School system while also working on a Masters degree. Once the MA was completed, I was moved to a high school position. I applied for teaching jobs in colleges and I received the opportunity from the University of the Pacific to take someone’s place who was going on sabbatical leave. So they flew me out for an interview. It was my first flight, first airport, and I met Bing Crosby! So I ended up taking the job, and the professor extended her leave to two years. The administration told me they wanted me to stay even if the professor came back. I ended up working there 19 years, moving from a temporary assistant professor to a full tenured professor, to chair of the department for seven years.

Once I left the chair position, I went back to teaching for another three years and came to realize that I missed the connections I had as department chair. As chair, I met people all over the country and there were a lot of opportunities and decisions to be pursued. I didn’t want to wait another three years to reapply for the position so I started looking around for other opportunities. I received a call from Georgia State University. The chair of their art department had retired and I was invited for an interview. Then I had another interview a few weeks later with the dean, who also invited my wife to accompany me. So I came in as chair of the art department. After a couple of years, we were able to change the name from Art Department to the School of Art and Design and my title changed from chair to director. I stayed in that position for 11 years. I finally gave up the director title but stayed at GSU to teach until I retired in 2000. I was there a total of 17 years.

SC: Were you always drawn to teaching?

CR: I read that you very logically started eliminating the jobs or positions that did not quite fit your personality, and the only thing left was the desire to teach. How did art play into that? What were your early influences that made you pursue an art education instead of another discipline?

LW: Well, I was always going to be an artist. I didn’t know what that meant, but I was going to be an artist. I have been drawing since I was six years old. When we lived in New York, I would look out the window — we lived in a six-story tenement — and I would see the people scurrying by and all of the streetcars. I would draw the apartment buildings and the people.

CR: So you married your passion with a vocation of sorts?

LW: Yes. We first lived with my sister Betty and her husband Charles when we moved to New York. Among other things, Charles did some artwork and he painted landscapes on glass. He painted backwards. He would put the detail in first and then cover it up with all of the other stuff. I would sit there and watch him, and that was kind of fascinating. I remember he gave me a book once. He was in the Merchant Marines for a while and therefore he had done some traveling. He gave me a book of van Gogh’s work. I would look through the book and somewhere along the way I came up with this notion that I wanted to be an artist. At one time I thought I’d be an architect, but someone told me that I’d have to get good math skills.

My first encounter with an art teacher was when I got to junior high school. Ms. Evans would encourage people to do things, and somewhere along the way she made the decision to send four kids from her class to the High School of Music and Art to take the entrance exam. I was one of those four kids. That was the first time I went to school with kids who were of different nationalities, from different areas. That was a wonderful experience, because everyone got along and everyone had goals that went along with either music or art. So I got a little influence here, a little influence there. I was introduced to the Museum of Modern Art, and I would go there on Sunday, and I would listen to what people would say about the art because I could learn from them. People standing in front of a Jackson Pollock painting, you know, would say, “Isn’t it this? Isn’t it that?” or “I see this and I see that.” I would be looking and looking and think to myself, “I don’t see any of that! I’ve got so much to learn.” None of the stuff was there anyway, it was just stuff that they were seeing, but I didn’t know that at the time.

So the notion of being an artist was developed, enhanced, and engraved by the time I finished high school. That’s all I knew — art and the supermarket, and I had some wonderful experiences in the supermarket. In Detroit, I’m taking some art classes and organizing shelves at the supermarket so that they look artistic. I loved the days when there was nothing on the shelf, because I got to go in and organize them myself as long as I kept everything in order. So, one day I would arrange the cans in a ribbon pattern based on the color of the labels. The next time I might do a checkerboard pattern, but all of the peas, beans, and corn were grouped appropriately. It kept changing, though, and I had fun doing it. When I finished an aisle I was able to look at the different patterns from different angles, and I came to understand perspective and design.

SC: Did you ever take pictures of the shelves?

LW: No, but I did occasionally send students to the supermarket for a couple of assignments so that they could see and understand perspective and design. I learned an interesting thing when I moved to the University of the Pacific; one of the reasons they wanted me was because I had taught at an elementary school and a high school, and because I could also do artwork. So I was teaching life drawing, painting, and art education. The students in the school of education had to take at least one art class in order to meet their credentials. So I became the art educator. For the students who only had one class with me, it was my opportunity to spark their imaginations, to show and teach them everything I could: drawing, painting, sculpture, printmaking, ceramics, etc. We made things out of cardboard boxes, found objects and scrap materials as well as the traditional art materials. [cont.]

LW: As you know, our move to the South is a major factor in Kara’s work now.

GW: Oh, it always was. I found one of her letters she wrote to me when she was in high school. She was angry, she was upset, she hated school, she said that I could ground her for life but she had to say what she needed to say. “No matter what,” I told her, “write it down.”

LW: In California, she grew up in a neighborhood and school setting where there were blacks, Hispanics, Asians, and whites, and they all related with each other one way or another. When we moved here, it was very different. There was black and there was white. You’re either with one group or the other, and the one was ostracized from the other. Also, we moved to Atlanta in 1983, right after a series of child murders. It was in the late ’70s, early ’80s, and that resonated with Kara, too. You know, she thought, “Why are my parents taking me to this place with all of these child murderers?”

GW: And it was on the news—that’s the thing. We had TBS, we had the Turner channel—we knew what was going on in Atlanta and we figured we wouldn’t be living in Atlanta, we would just work in Atlanta.

LW: The first year we lived here we were in Decatur in a townhouse, and then we bought a house in Stone Mountain. We would get announcements to attend Klan meetings. So the first one we laughed about, and I said “Hey wife! We’ve been invited to a Klan meeting, we’ve got to go!” And she was like “Shh—Kara’s home.”

GW: And a Klan member used to own a gas station at the corner of Memorial Drive [in Stone Mountain], and I always made a point to never go into that place.

LW: Every year the Klan would have their annual march on the mountain and they would congregate at the gas station as the starting point to go up the mountain.

CR: So that must have been quite a change for all of you, though—not just Kara. After being in California and Detroit. It must have been quite a shock to have to deal with post-segregation Georgia.

LW: When I was at University of the Pacific, there were two black faculty members hired in the same year. It was Juanita Curtis in the College of Education and myself. We were the first black faculty members at that institution. There were only about three or four black students at the institution at that time. Everybody else was upper-middle class white. And I was there, like I said, 19 years. I came to Georgia State University and one of the questions one of the faculty members asked me was, “How are you going to react when you go to your first faculty meeting and see all of these white faces? How are you going to respond to that?” I was blown away.

GW: Yes, we both went to integrated schools.

LW: I thought, “Where does this guy think I came from?” [laughs]

GW: Our goal was integration and that’s how we lived in California. We said we weren’t going to live in a section of town just because other people lived there. We were going to buy a house wherever we could buy a house. We decided we would put up with what we had to put up with. Now, our retirement years, is the only time that we have lived in a predominantly black neighborhood, aside from growing up.

SC: Did your work change as you moved from Detroit to Stockton to Atlanta?

LW: When I moved to California I was enamored with the landscape — the openness and the big sky. I was doing more landscape stuff than I had before. In Detroit, the work was predominantly figurative. The shift from California to Georgia … I guess there was the impact of the Civil Rights movement. I was very conscious of that. I did a few things that touch on the ideas and the ideals of the civil rights movement without falling into the category called “black art.” When that term came around, there were a number of questions and issues related to it. I had some issues with it, but I understood the need for the term at that time. The whole notion of doing work that articulated something about who you were or the people you knew and so forth—I was doing some of that already without it having a label. Then all of a sudden it was “black art.” Over the years, various groups tried to define the term, but the definitions were never really satisfactory. The worst one that I came across was the one the Black Panthers put on it. They said, “Black art is work by black people, for black people, about black people.

CR: The black experience, right?

LW: Yes. Anything short of that was not acceptable. That eliminated people like Henry Ossawa Tanner, Edward Bannister, and a bunch of others. That just didn’t seem right. So there’s got to be more than that. You can express who you are in ways that allow you to be human, natural, honest, without having to package it into a “thing.” When I was finishing my graduate work in Detroit, I was looking for “a style.” I didn’t know what that meant, but some people had told me things like, “the shapes and lines in your sculptures don’t look like they were done by the same person who did these drawings or paintings.” So I thought, “Oh. There must be something missing. It must be style.”

So I took a drawing, a painting, and a sculpture class at the same time, with the intention of developing a common thread. What I discovered was not a style at all, but structure. It was like, you take an arm, remove the skin and you reveal muscles, and tendons…you see striations. You look at the landscape in California and you see similar striations. There’s tension there – there is push and pull. It was happening and I could see it in the landscape, I could see it in my sculpture, and I could see it in my arm, I could see it in my leg, and I could see it in people and I began to see it my paintings.

Driving down the street you look in the side view mirror and you see what you just passed: you saw it going and now you see it behind you. So I created a series of paintings called Microscapes. They were little circular paintings with things, kind of abstracted, inside and outside the circle. That ultimately led to another series about people called The Children of Society. The title came about because of a song by Janis Ian called “Society’s Child.” Those were the hippie days. [laughs] The Children of Society series was characterized by a circular format and by images of people pushing against a barrier. There’s a line that runs through about the upper two-thirds of the painting, and this line was like a competition stripe. People were living down there [bottom third] and sometimes they were very complacent, sometimes they were agitated, sometimes they were struggling. They were trapped in this environment. That series further evolved when we lived in Mexico for four months, in Guadalajara.

I did a series called Remnant Series that contained bits and pieces of things—ticket stubs, ripped portions of magazines, whatever—that would get laminated into a space. I started wondering where some of these images and ideas were coming from and decided that they related to my time spent in New York as a kid. So I went back to New York in 1982 and retraced some steps and came away with the notion that, indeed, my time in New York was a factor in some of this work, looking at urban environments, condemned signs on buildings, graffiti markings, gang tags as well as official information all focused on walls. I started using a brick format somewhere in the painting and that definitely focused on the barrier surface and launched the “Wall Series,” which replaced the “Remnant Series.” With this wall, I could put things on it — more and more posters. I was literally in some instances peeling posters off walls and laminating them to the canvas

SC: And now Mark Bradford does that.

LW: Yes. Mark Bradford does it and he does it in a much bigger way too. I peeled a little bit here and there, but he takes a whole section. Anyway, that series kind of grew and grew and reached a point where a shadow was introduced—representing a person who was either homeless, ill, sick or struggling in his own way, the kind of situation where you might walk past this person.

SC: Where are the posters from?

LW: Various places. There are some from New York, but I don’t know which ones they are any longer. This one’s from Mexico. This one’s from Brazil. Some from Decatur.

SC: Are you selective or do you use random posters?

LW: No, I don’t put the things up there with any sort of selectivity other than my interest in color, pattern or shape. I don’t try to match things up. I’ll mix up things with something that took place this year versus something that took place another year. So there’s no chronological reason for them to exist together.

SC: What about these works with the cables?

LW: The cable thing came about a little later, around 2007 or 2008. The idea was to make the work a little more up to date. I met a kid who took a look at my work and said, “I thought you were much younger.” I said, “What made you think that?” He said, “I took a look at your work and I thought you were into hip-hop.

CR: What do you think of hip-hop?

LW: What do I think of hip-hop? I could take it or leave it.

CR: Who are some of your favorite contemporary working artists?

LW: Mark Bradford for one. Wangechi Mutu.

SC: Earlier you mentioned that you had a Van Gogh book that was formative for you as a kid. Are you influenced by his work?

LW: No. There have been a lot of people who’ve influenced my work over the years, but none of it stands out. Raymond Saunders was a big influence on my work, and I didn’t know him at the time. E.J. Montgomery, who used to curate exhibitions for the Rainbow Sign Gallery in California made a comment once, “I’d really love to see your work and Raymond Saunders’s work together” and I said, “Who’s Raymond Saunders?” I eventually met him. Rauschenberg’s series of Combines was an influence, and I’m still putting things together that don’t belong together. [cont.]

SC: Did you visit Georgia when you were a kid living in New York? Did you visit family?

LW: Once I moved to New York, I never came back to Georgia. When I was in Detroit, I came to Georgia once, because my brother was ill. But it was a very short trip and I didn’t experience anything else other than seeing him because I had to get back for graduation. The only other time I came to Georgia was to see relatives who had not seen our youngest daughter [Kara] or any of us for a while. So we got in the car and we drove from California, making stops in Detroit, Cincinnati, New York, Washington D.C., South Carolina, Florida, Georgia and back.

SC: How long did that take?

LW: A little over a month. I said “never again.”

SC: So it didn’t feel like you were coming home in any sense?

LW: Never. Well, no place is home anymore, because I’ve been here longer than I’ve been anywhere else—since ’83.

SC: What about your legacy?

LW: One time I thought it would be a great idea to have a creative foundation, a foundation where we could share the work with museums or open it to the public. But I had to rethink that idea because setting up a foundation is not as easy as it sounds, and I won’t be around to police it.

CR: One stipulation you mentioned is that you want people to see it — you don’t want it boxed up or stored somewhere.

LW: There’s the idea of giving it away to an organization that would care for it. I won’t give it to a university unless it has a museum, strong curatorial program because they don’t have the resources to take care of it. I donated several pieces to the University of the Pacific, then when I was retired, I wrote them because I wanted to borrow a couple of pieces and they couldn’t find them. I was so annoyed.

Unfortunately, the attitude still exists among a lot of people that in order to be a real collector of art, you have to go to New York, that you can’t get it here in Atlanta. There are some other people for whom, if you’re from Atlanta, they don’t even want to look at you.

The other thing that’s annoying about Atlanta is that our visibility has gone downhill as far as I can tell. There used to be an art critic writing for the paper, so there was an opportunity for exhibits to be reviewed and so forth. And that started changing with the Internet, where there were more opportunities for people to write about the arts. But there are some limitations around who gets to see that, and I don’t think it’s the same audience that you had when it was just the newspaper. There’s nothing wrong with shifting to a different audience, it’s just that there’s a whole bunch of people out there who are missing out. Even the way galleries and museums would send out announcements about exhibits changed to using email as opposed to U.S. mail, and a lot of people got left out because they didn’t have email or didn’t pursue the information in the way that other people did. Some got back into the game and some didn’t. It’s hard for an old guy like to me to keep up with who’s doing what, where, and when. I am not going to look on a computer everyday.

SC: What do you read?

LW: I’m a subscriber to Art in America and ArtNews and the International Review for African American Art. All that’s fine except most of what happens in those magazines is about someplace else as opposed to what’s happening here in Atlanta. That’s kind of unfortunate and I know there have been some efforts to try and bridge that gap and give more exposure for Atlanta artists. In fact, the organization Artadia has made an effort to do that and they’re still doing that not just for Atlanta but also for other cities. [Walker received an Artadia grant in 2009.

SC: So, you thought it was improving here for a while –

LW: Well, it was improving over what I had experienced in California. But in the long run there’s a whole new set of problems here that are different than in California. And those problems are predicated in some ways by cliques. I guess I’ve been out on my own for a long time. I’ve heard someone say on more than one occasion: “curators make artists.”

SC: I feel like that’s more true these days, whereas critics used to wield that kind of power.

LW: If there’s any sort of truth in that, that means you’ve got to make sure that your relationship with curators is up to par, always. You don’t want to rub anyone the wrong way because you’re cutting your own throat.

SC: How would you like to see that change?

LW: Relative to me? It would be nice to have some more visibility in terms of my work. It would help with the decision about what to do with [all my work]. If nobody is interested in it then that helps make that decision. For me, the opportunity to be more visible hasn’t happened a lot. There are some people in the area who know me and my work, a couple of collectors here and there and so forth. But I don’t have widespread visibility; I’m like an unknown entity.

CR: Did you ever feel like you missed out on New York?

LW: Yeah, I felt I missed out on New York because New York missed out on me.