When I landed in Houston, I knew exactly where I was heading first. Not to the Museum District or Trill Burgers. Not even to the hotel. I grabbed the rental car, pulled up the directions, and drove straight to Tom Bass Park. I wanted to start with John T. Biggers. I had a whole list mapped out, but this felt like the right place to begin—with a mural that still breathes with the rhythm of the neighborhood, tucked inside a quiet craft house in a well-used public park, holding the memory of sunlight on its surface.

I came to see murals by Biggers—murals that live where people live in Houston: parks, schools, community centers, and cafeterias. These are the same places where Biggers himself lived and worked. The fact that the murals are open, accessible, unguarded is part of what gives them their power. People can walk right up to them, sit with them, and eat lunch in front of them. And if you’re not looking, you might miss them altogether.

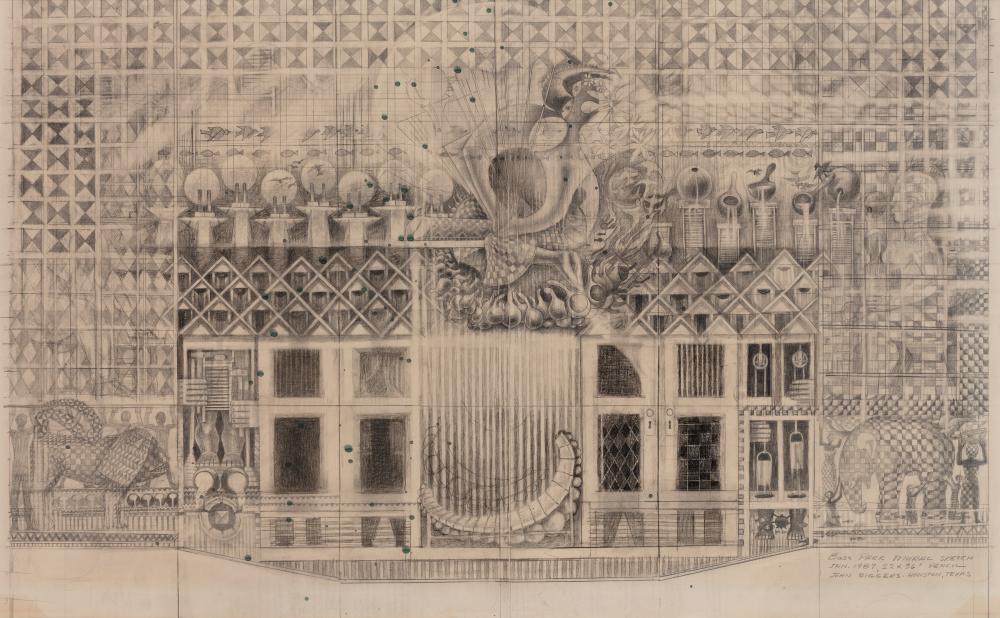

The mural, Song of the Drinking Gourds (1987) is enormous. It spans a wall inside the Tom Bass Regional Park Craft House, but one can already feel its presence before you step in. And once you’re in the room, it towers overhead. The piece is structured like a quilt, grids of earthy ochres, muted greens, and clay reds. The composition doesn’t unfold in a neat, left-to-right narrative, instead, it reads like a woven story, geometric and layered, full of symbols drawn from African, African American, and Southern folk traditions.

At the center, a blackbird hovers over a musical instrument. On either side, a king on a lion and a queen on an elephant watch over the scene. Look closer, and one sees birds, vines, spirits, symbols of water and fire, and a coiled serpent—all arranged in a way that feels both ancient and urgent. It doesn’t ask to be explained.

The mural is named for the spiritual “Follow the Drinking Gourd,” a coded song that led enslaved people to freedom via the Underground Railroad. He saw the gourd as the perfect shape: a vessel, a symbol of life that was used to carry water, make music, and hold seeds. The gourd is a recurring symbol for Biggers. Biggers doesn’t depict the song literally; he channels its deeper meaning—navigation, survival, ancestral guidance—into something cosmic and resonant. You can feel the water, the fire, the stars, the ritual. It’s a mural about how people move, how they remember, how they live. And though the surface has weathered over the years, the song is still in there. You just have to lean in and listen.

John T. Biggers relocated to Houston in 1949 to build the art department at what would become Texas Southern University. He had studied at the Hampton Institute at Penn State University with Viktor Lowenfeld. There he forged a singular visual vocabulary that drew from African art, Southern Black life, Mexican muralism, and regionalist storytelling. In Houston, he found a city on the edge of transformation, still deeply segregated but pulsing with energy. He made Houston his home, and over the decades, the city became the site of his most ambitious public work.

The murals tell stories that are vast and mythic yet grounded in real places and lives. They mark Houston like points on a constellation. Driving between them one traces something bigger than a biography—the visitor finds a cosmology of African American life, ancestry, and perseverance.

Take Family Unity (1974-1978), which spans sixty feet across a long wall in the bustling student center of Texas Southern. Students pass by with lunch trays. There’s no admission price, no museum hush. Biggers called it a turning point —not just in scale, but in process and vision. His earlier murals often followed detailed studies and linear narratives. Instead, this one unfolded image by image, drawing by drawing. It’s an epic but one built from the textures of ordinary life: wash pots, porches, ladders, quilts, and serpents. The mural reads like a visual prayer, with references to creation, birth, history, and the cosmos. At the center is Biggers’s “morning star”—a radiant skull, womb-like and full of light, from which knowledge, family, and spirit emerge. You see ancestors, future generations, shotgun houses turned cosmic symbols, and strong-bodied women with their backs to the viewers, carrying homes, children, and galaxies. This is a mural of reverence, of weight and transcendence, of home and the universe at once.

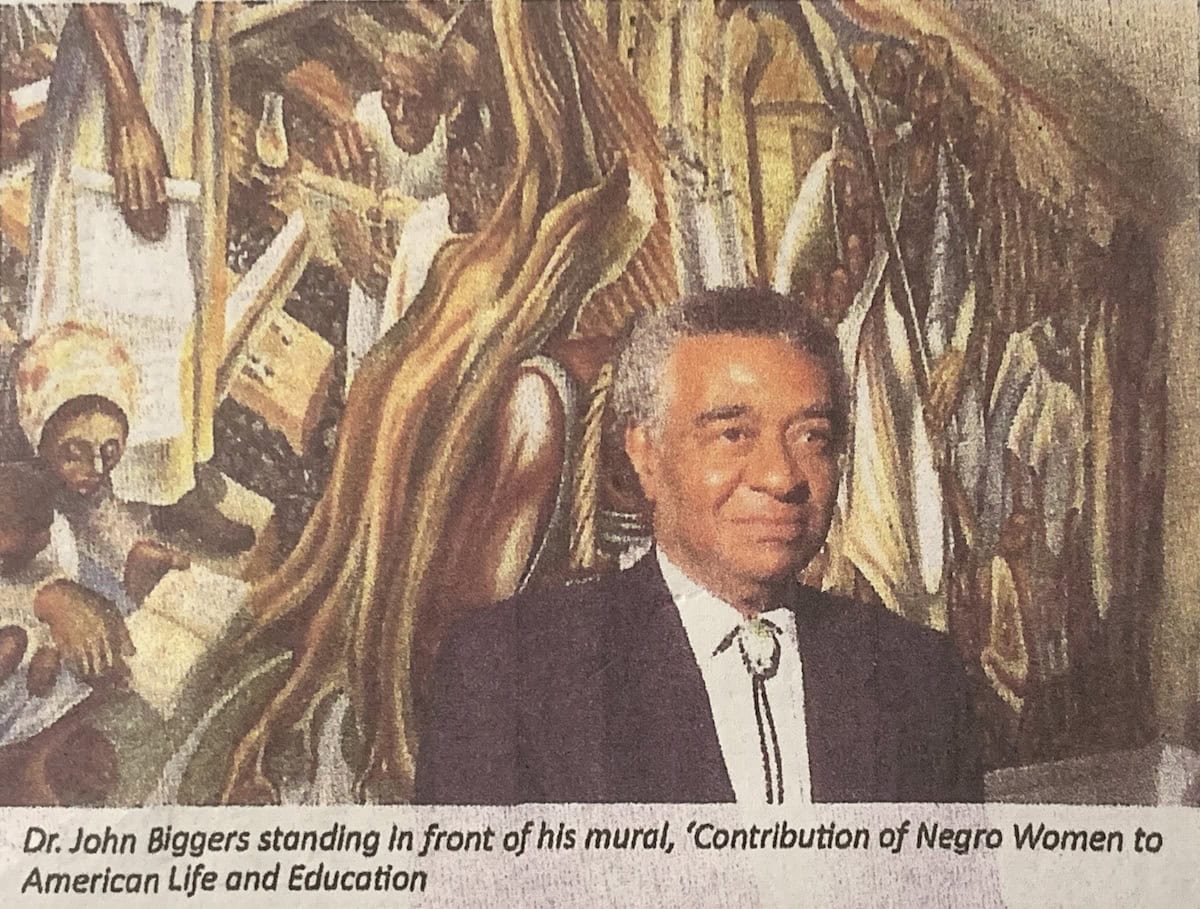

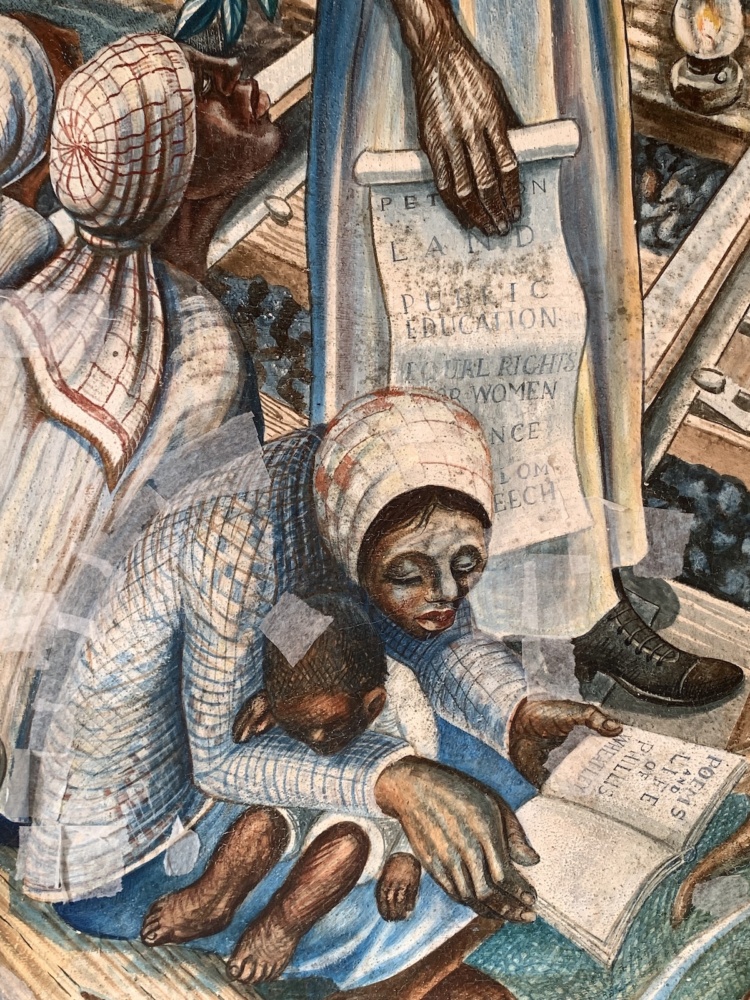

Not far away at the Blue Triangle Community Center, Biggers painted one of his earliest and most politically charged murals: The Contribution of Negro Women to American Life and Education (1953). The mural stretches twenty-four feet across the back wall of what was then the YWCA serving Black women and girls. It centers Harriet Tubman and Sojourner Truth—two monumental figures not as distant icons, but as muscular, commanding presences. Tubman leads with a rifle in one hand and a torch in the other, carrying both fire and force—freedom lit and fiercely defended. She’s less Moses than a flesh-and-blood Statue of Liberty. Truth, on the opposite side of the mural, preaches before a crowd gathered on railroad tracks, backed by a church and holding a scroll that demands land, public education, and equal rights for women. This is education as liberation—the written word as a weapon.

What struck me most about this mural is not just its political vision but its attention to labor—bruised feet, calloused hands, figures bent under sacks of cotton and still moving forward. Biggers gives weight to struggle and power to collective action. His Tubman leads not with ethereal grace but with militant steadiness. That alone unsettled some of the YWCA patrons when the mural was unveiled. These women weren’t “pretty,” they said.[1] But they were true.

A few miles away, at the University of Houston’s downtown campus, Salt Marsh takes a different approach. Completed in 1998 with help from Harvey Johnson, a professor at TSU, it pulses with color and ecological urgency. The campus overlooks Buffalo Bayou, where Biggers saw not just a waterway but a threatened cradle of life. The mural is both literal and metaphoric: children reaching upward from a watery baseline, animals swimming through layers of history and pollution, and celestial bodies tracing a cosmic arc. The sun and moon are a tortoise and a hare racing across the sky. A golden serpent forms the rooflines of shotgun houses. The message is simple and profound: transformation, metamorphosis, rebirth.

Biggers brings together Native American symbols, African cosmology, and the Houston landscape. The story may be “a children’s story,” as Biggers called it, but it carries the weight of generations. It’s not just about family; it’s about the ecosystem that sustains it.

Back in Southwest Houston, right across from Tom Bass Park, is a smaller park where Biggers’s Christia V. Adair (1983) mural sits in a state of neglect. The work memorializing the suffragist and civil rights worker was the last mural Biggers completed while still teaching. Inspired by the Dogon houses of Mali, the octagonal pavilion sits in a clearing, open on three sides, and the mural inside is like an altar screen. It tells the story of Christia Adair’s entire life—her birth, her education, her music, her church, her activism. And it’s filled with what Biggers would later call his “developing iconography”—rails and camels, beetles and moons, wash pots, and an ancestor figure built from shotgun rooflines and rub boards.

They shape—and are shaped by—their settings: the dining hall, the community center, the craft house, the bayou. They’re part of the city’s skin.

In 2017, Hurricane Harvey did considerable damage to several of Biggers’s murals in the Houston area, but to see the mural at Adair Park deteriorating under the elements is a gut punch. I knew it was outdoors, and I knew it had suffered over the years, but nothing prepares you for how rough it looks up close. It’s not just deterioration—it’s a kind of forgetting. Harris County Precinct 1 manages the park, and a restoration was completed in 2014 by EverGreene Architectural Arts. But in Houston, another hurricane is always around the corner, and without regular maintenance or a long-term preservation plan, even the best restoration won’t hold. One of the city’s most eloquent storytellers is being left to whisper into the void.

Biggers didn’t love this mural. But he recognized its importance. From it came the shotgun house motif, the quilt geometry, and the triangular mother figures that would shape so much of his later work. And in truth, standing in that pavilion, even in its weathered state, there’s something sacred about it. You feel how the structure relates to the world around it. You understand Rivera’s lesson: murals don’t just sit on walls—they belong to the spaces and people they serve.Each of these works—Family Unity, The Contribution of Negro Women, Salt Marsh, Song of the Drinking Gourds, and even the damaged Christia V. Adair—offer different facets of Biggers’s vision. They span decades and styles. But they all return to a few core ideas: the power of women, the continuity of ancestry, the rhythms of labor and nature, and the need to see the cosmic in the local. It matters deeply that these murals live in public places. Not just because they’re accessible, but because they’re alive in their surroundings. They shape—and are shaped by—their settings: the dining hall, the community center, the craft house, the bayou. They’re part of the city’s skin.

[1] When the mural was unveiled, some of the YWCA’s middle-class patrons reportedly objected to Biggers’s portrayal of the women—not because of what they stood for, but because they weren’t “pretty” in a conventional sense. As Biggers later reflected, these figures had “gnarled, calloused, trembling hands,” “bruised feet and bodies,” and wore “gingham and sackcloth.” They bore the marks of labor and history. Their beauty wasn’t ornamental; it came from strength, survival, and a life of collective struggle. See Stacy I. Morgan’s Rethinking Social Realism: African American Art and Literature, 1930–1953, pp. 96–97.