To understand the mythology of James “Son Ford” Thomas, I thought I should start with forensic dentistry. My plan was to extract one of the human teeth from the jawline of one of Thomas’s iconic skull sculptures, ship it to my odontologist friend, and have him search existing dental records for a potential record match. Needle in the haystack, sure, but an interesting exercise. There were, rightfully, concerns. If someone is identified, what do we do next? Where could the discovery lead? Do we write the names and biographical information about the deceased? What about that person’s family? A very legitimate question would be about me, a white writer, potentially stirring up old trauma for a Black family. This was a genuine and honest concern, big enough that I walked away from the gimmicky idea—but something didn’t sit right with me. This concern gave credence to the farcical tale that Thomas was out in a graveyard digging up members of his community as art supplies. That’s a felony! But it is also a hell of a story.

What do we know to be true about Thomas? He was born in 1926 in Eden, Mississippi, a village in northern Yazoo County. His maternal grandparents raised him, bestowing the nickname “Son” on him as a term of familial affection. His uncle, Joe Cooper, the noted Delta blues guitarist, was pivotal in Thomas’s artistic journey. Having no money for toys, Cooper showed Thomas that he could walk a couple miles to get some clay to sculpt into miniature mules, rabbits, cars, and tractors. Things to play with. Items to sell for money to buy school supplies: crayons, paper, and pencils. At one point, Thomas sold a box of clay horses to a man from Vicksburg for $3—this was more money than either of his grandparents earned in a week. He also learned the basics of blues-style guitar from his uncle and, after saving his wages from working as a cotton sharecropper, he bought his first guitar from Sears Roebuck & Co. at the age of sixteen. Every weekend, he played the blues in the juke joints and barrelhouses around Leland and Greenville. Long before he made ceramic skulls, there were speculations and innuendos about Thomas. As is often the case, perhaps they were cautionary tales from the pulpits of the church. As art historian Paul Arnett put it, “I think in the old days, certainly blues singers occupied a place that was kind of in between respectable and not respectable because most of their gigs were house parties and Saturday night joints. And that I think blues-style guitar got the association with devil music because that’s what preachers preached against on Sunday morning, it was Saturday night.”1

By age thirty-five, Thomas had a wife and six children to support. The family moved to Leland, Mississippi, after his mother arranged a job for Thomas as a porter at the Montgomery Hotel. Not long after the move, his stepfather, who was a one-armed grave digger, got him a well-paid job “opening and closing graves.” Thomas’s occupation, his art, and his music combined to prompt his friends and neighbors to associate him with death.

The first time he made a skull was as a mischievous ten-year-old living with his grandparents in Yazoo County. Knowing that his grandfather was scared to death of ghosts, Thomas sculpted a rudimentary skeleton topped with a giant skull with hollow eyes and corn for teeth. He placed it high up on a shelf. They had no electric lights, and when his grandfather walked into the dark room and lit a lamp, he lost it. Terrified, he dropped the lamp and ran straight to Thomas’s room, telling him to never do it again.

Much has been written connecting Thomas’s sculpted skulls to hoodoo, a form of traditional African American and Afro-Caribbean folk magic. Hoodoo is not to be confused with the West African religion of voodoo, which is often used interchangeably in writings about Thomas’s work. In hoodoo, the head is a common theme, an effigy that can give its victims headaches and loss of memory, ultimately leading to death. “To create a man’s image is to have power and control over him.”2 Thomas frequently referred to his portraits as “futures.” Local legend said that Thomas had the power to give or cure disease, similar to a hoodoo doctor. Identical to the folklore that surrounded many artists working in the rural South, there was community-wide awe surrounding each aspect of his life.

I think of Thomas’s sculptures as distinctly American, being very literally of the place they were created. The artist sourced the clay for his busts and skulls from the silty bottom of the Yazoo River, the lower hills around Greenwood, and the clay soil just around Leland and Black Bottoms. The soil in the Mississippi Delta is so sticky they say it has the consistency of a cold, gray gumbo. It has low moisture, so Thomas would have to soak it in rainwater overnight and then combine it with plaster of paris. His early heads, especially, were unfired, being just left to dry and become the color of bones. Before he had money for paints, Thomas would take the stone-colored hill clay and bake it in the fireplace. His little animals and early skulls would turn a burnt red and were as sturdy as bricks. Left unfired, the majority of his early works crumbled as soon as they dried. Before Thomas sculpted his either the skulls or the busts, he would cover his hands with Vaseline in order to be able to sculpt more smoothly, creating the form of a human head and then using a knife to cut out the eyes and split and spread the mouth. He shaped the nose and nostrils with a stick and accentuated the hollowed-out eye sockets by lining them with reflective tinfoil, or filling them with glass marbles or matchstick heads.

Thomas’s skulls live in a peculiar place, unequivocally between ghoulish and absurd. Each a hefty lump of clay crudely worked into the shape of a skull, they are squat and feel as though each of their identities comes from being mashed down to their very core. Unlike his full-face sculptures, the skulls are limited in their features, yet no two appear alike. When seen in groups, the skulls feel like a boneyard phone directory reflecting the artist’s ever-expanding community. Some represent very real people in his life. Others do not. The more articulated faces on the busts would come with many more variations and representations: human and artificial hair, tufts of raw cotton, plastic beads, aluminum foil earrings, and sunglasses. White faces are often crudely brushed with red paint. On occasion, to appeal directly to collectors, Thomas made busts of recognizable figures; Abraham Lincoln and George Washington were recurring characters.

The busts were routinely inspired by people in Thomas’s world, and resemble faces of people in his Black community. They sit cool and proud and are almost gentle. In contrast the misshapen white faces are frequently mangy and mangled—unpleasant neighbors, to say the least. Arnett has said that Thomas was “making pieces that were self-consciously grotesque or even ugly. Many of his people were not intended to be beautiful. It’s what being a human is all about. That itself is a part of this mythologizing, just projecting this need to maintain a hierarchy through how we perceive other people’s thoughts and creations.”3

This brings us back to the teeth. Where (how?) does an artist acquire a supply of human teeth to routinely use in their sculptures? This is where the mythology and misconception of Thomas as an isolated rural graverobber starts to break down. By the early 1970s, Thomas had begun continuously traveling the world as a successful blues musician, playing shows, and meeting art collectors. Between 1971 and 1976, he played at Jackson State University, the University of Maine, Tougaloo College, and numerous shows at Yale University, among other institutions of higher learning. He played large festivals in Scandinavia and Germany, as well as the Smithsonian Festival of American Folklife in Washington, D.C. He recorded albums in the United States, the Netherlands, West Germany, and Italy. He exhibited his sculptures at the Corcoran. A fair number of wealthy collectors were fans, and more than one worked as a dentist.

Originally the busts’ teeth were kernels of corn, sometimes colored a dull white with paint from the ten-cent store. At times, the corn would get a clear varnish to make them shine. But Thomas had to find an alternative once he realized that a bust he had given to Shelby “Papa Jazz” Brown was breaking apart at the lips because the corn was sprouting. Sometimes he lined the jaws with pebbles or—frighteningly—filled them with dentures. There is something particularly chilling about the contrast between the surface of one of Thomas’s bone-dry skulls and its ill-fitting shiny prosthetic teeth.

At the 2015 exhibition James “Son Ford” Thomas: The Devil and His Blues at NYU’s 80WSE gallery, I was troubled to see that the show’s catalog included the passage “organic human remains (human teeth and hair, extracted as part of his work as a gravedigger)” in a description of one of the works that perpetuates the rumors. After simple sleuthing, reading interviews with Thomas online, and speaking with his most dedicated collectors, I discovered that dentists in both Memphis and Richmond had happily supplied Thomas with jars of human teeth.4 A psychologist from Lafayette, Louisiana, was known for sending him sets of dentures.5 Thomas frequently would switch from human teeth back to pebbles because his supply of teeth had “run out.” Access to human remains was never as simple as clocking in for work at the graveyard.

Perhaps part of the missing puzzle was the mysteriousness of the artist himself, as a little mystery is good for business. When watching Thomas in documentary films6 by William Ferris, we see a bare, broken-down, two-room house. Forgoing bigger audiences in Chicago, St. Louis, or New York following his musical success and international fame, by choice Thomas continued to live in this house throughout his adult life. Arnett shared with me accounts of various collectors of the sculptures arriving in Leland on annual trips with several thousand dollars of cash in tow. But despite Thomas’s growing means, the home fit an image. When blues fans, art collectors, and photographers saw him, they preferred this ramshackle backdrop. They would come by with money in exchange for a song or a photo at his doorstep. Thomas would often make as much money staying at home as he might bring home from the concert circuit. Perhaps the house—and the rumors of being the “hoodoo man”—were all part of the show.

On stage or off, Thomas could put on a show that built a broad and diverse fanbase. Before it opened to the public on January 13, 1982, First Lady Nancy Reagan toured the exhibition Black Folk Art in America 1930–1980 at the Corcoran Gallery of Art, a seminal show that surveyed previously neglected histories, bringing to light the undeniable achievements of many southern self-taught Black artists. As she walked through the galleries, six of the exhibiting artists spoke with her personally about their art, inspiration, materials, and lives. When the group got to Thomas’s work, he leaped into his amusing story about his start being a prank to scare his grandfather, who was afraid of ghosts. Mrs. Reagan giggled and replied, “Aren’t we all?” They took a photo together, which Thomas proudly hung in his home for the rest of his life. Mrs. Reagan was so charmed by their interaction that she hired Thomas to perform for a fundraising dinner in Jackson, Mississippi, the following year. He was paid $100.7

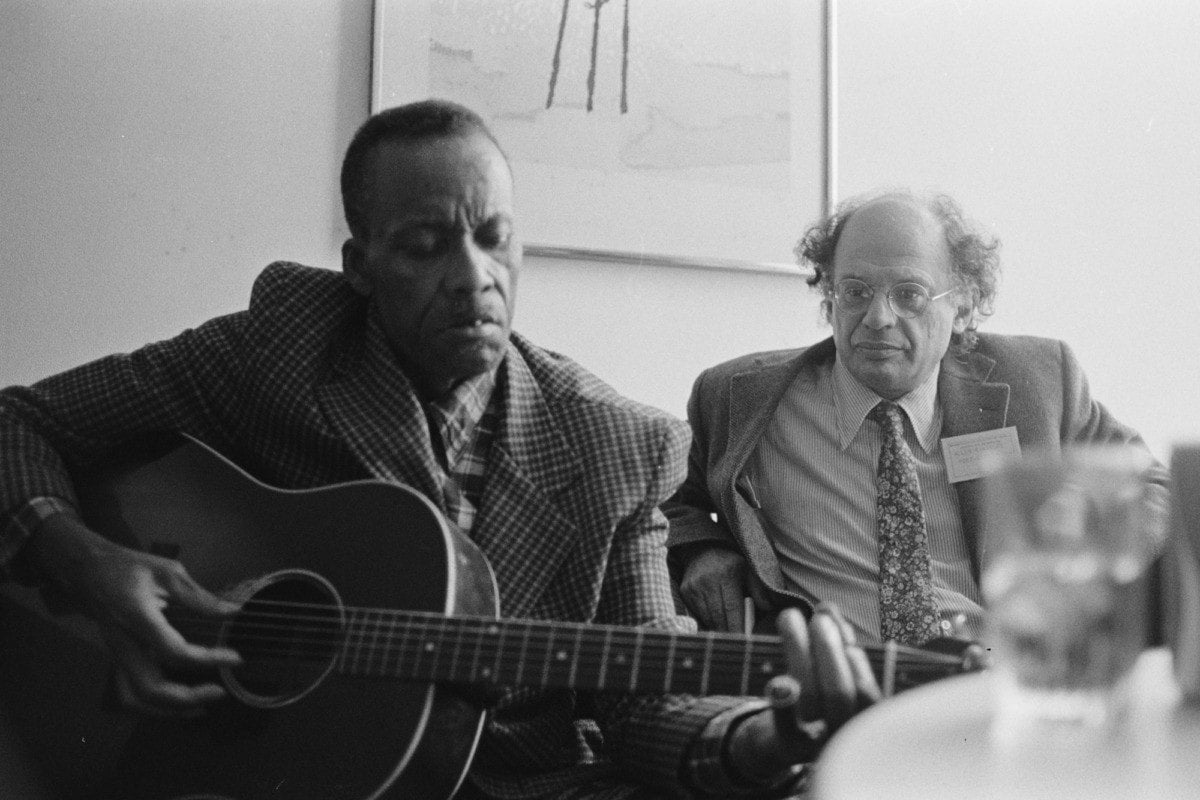

Earlier, in December of 1980, William Ferris and Thomas traveled to Houston to participate in a panel for the Modern Language Association—Ferris to speak, Thomas to sing. As Thomas performed, Ferris spotted an enthralled guest in the front row, who turned out to be Allen Ginsberg. After the event, they ended up back in Ginsberg’s hotel room playing music and exchanging lyrics. This scene perfectly embodies Thomas’s magical life and his place among the landmarks of our nation’s cultural history. A story could nearly place Thomas in any room, on any stage, in any museum, with any people, and I would believe it.

Arnett feels that this sort of lore hovers around most artists/musicians of the region: “Virtually every Delta blues singer is surrounded by this type of mythology. You think of the most famous of all, Robert Johnson sold his soul to the devil, went down to the crossroads, sold his soul to the devil so that he can learn to play guitar like that. Well, maybe he did go to a crossroads, and maybe he did meet the devil… I doubt it. And so, it just looks like to me, part and parcel of just the ongoing romanticizing of the blues and its practitioners.”8

After wrapping up my deep dive into Thomas’s skulls, the one thing that felt certain about was that I’d never arrived at a definitive truth. The art world figures who speak of or write about James “Son Ford” Thomas seem to live in an intricate game of telephone, each knowing roughly similar stories and believing that the others have the incorrect details. It seems that long ago, there was an unspoken contract made, the artist and the audience each projecting a narrative that added to an aura of mystique. Be it for self-preservation or profit, Thomas, ever the showman, developed stylistic choices with both his aesthetic and narrative that best fit the hierarchy of artist/collector.

[1] Arnett, P. (May 22, 2021). Atlanta, Georgia. Personal interview.

[2] William R. Ferris, “Vision in Afro-American Folk Art: The Sculpture of James Thomas,” in Afro-American Folk Art and Crafts, ed. William Ferris (Jackson, Mississippi: University Press of Mississippi), 121.

[3] Arnett, P. (May 22, 2021). Atlanta, Georgia. Personal interview.

[4] Philip Walker and James “Son” Thomas, Bomb, July 1, 1983.

[5] The Diversity Times, Culture Channel.

[6] Ferris, William and Josette, director/producers. Sonny Ford, Delta Artist (1969). Folkstreams.

[7] James “Son” Thomas, Hedges Projects.

[8] Arnett, P. (May 22, 2021). Atlanta, Georgia. Personal interview.

This essay is part of Burnaway’s yearlong series Word of Mouth.

Find out more about the three themes guiding the magazine’s publishing activities for the remainder of 2021 here.