During the height of the global COVID-19 pandemic, artist Steven Cozart craved community. As the quarantine lifted, Cozart, like many others, struggled to establish a new normal in the aftermath of sustained social isolation. In the summer of 2020, as the pandemic raged on, the murder of George Floyd spurred waves of protest and social unrest. The virus, set against a persistent plague of racism and violence, heightened anxiety, fear, and anger within the Black community and among people of color.

On a Fall day in 2020, Cozart sent an email to a group of Black male artists. At the time, he was looking to create a space that would introduce artists to one another and share information about resources for them to weather storms of economic, political, and social uncertainty, but it evolved into something much larger. Through email and text, he said, “I know you don’t know each other, but you all know me. I would love to get online for one hour.” What started out as a quick video meeting one Sunday turned into a much-needed catharsis. And within this cultural climate, a new artist collective was born.

In creating a space for Black and Brown men to virtually gather and “chop it up” (a colloquial term for old friends spending their time together reconnecting), they not only forged a strong bond but also formed a powerful network of artists committed to creative, professional, and personal growth. Within three meetings, the group named themselves The Chop Shop Artists Collective. The sixteen men who make up the Chop Shop hail from various points along the Eastern seaboard, representing a range of art forms from figurative painting and portraiture to assemblage and sculpture. The oldest artist in the group is eighty years old, and the youngest is twenty-eight. Many of the members of the collective work in education, with each member bringing their own unique skill set, perspective, and professional experiences to monthly group sessions that include critiques, knowledge sharing, and thought-provoking discussions on the art world and their respective roles within it.

The Chop Shop shares a structural and philosophical resemblance to historic collectives like Spiral in New York, a group created during the Civil Rights movement, and regional collectives like AfriCOBRA, which formed in response to the Black Power movements of the late 1960s and early 1970s.

In May, Steven Cozart and Roymieco Carter, the Chop Shop’s founding members, curated the group’s debut exhibition titled Chop Shop: We Are Here at the Harvey B. Gantt Center for African-American Arts + Culture in Charlotte, NC. In this interview, the two curators discuss the collective, now in its fifth year, and its decision to mount a group show that is both an introduction and a declaration of presence. The following conversation was edited for length and clarity.

COLONY LITTLE: Steven, please take us back to the day you decided to send that fateful email during the pandemic that led to The Chop Shop.

STEVEN COZART: It was November 2020. We were isolated online, and people had transitioned to having group meetings and providing education offerings on Zoom calls. I sat in on a workshop regarding minorities applying for grants, and I found it frustrating because the information offered wasn’t cohesive. At that point, I wanted to bring my own group of people together to talk. I started making a list of people in my mind to introduce: I thought it’d be great if this artist met that artist, that artist met this artist…I sent out a mass email saying, “All I want is one hour of your time. We can just talk about what we’re doing in the studio.” When we talked, it was supposed to be a one-hour meeting, and it ended up lasting four hours.

ROYMIECO CARTER: I’m more of a forced extrovert introvert; my favorite spaces are in my studio or classroom. Steve is an introvert too, but he has a magnetism that really brings people together. It didn’t surprise me that he knew all these people who were naturally brought into his orbit. It started out as a community conversation asking, “What’s going on with us?” I always have more questions than answers, and Steve happens to be the person that I always direct those questions to. When we talked as a group that day, we found out everybody had questions and everyone had a perspective.

CL: After four hours, it was quite clear that this was a space that was needed. What made you decide to schedule the next meeting, and how did the formal structure of the collective take shape?

SC: The feedback from the participants was great. Some wanted to meet every week, or twice a month; we settled on once a month, and we put a time limit on the meeting. We faithfully met every month starting that November. The first thing one of our members, Berrisford Boothe, asked was, “Is anybody recording this?” If someone missed a meeting for whatever reason, they can go back and play it in the background of their studio and listen to it like a podcast. There were debates about artists and critiques of our work. I remember the first formal critique, everybody sent in work (in shared drive), and we talked about it, getting everybody’s opinions; the crits eventually became more informal, and somebody would literally just bring a piece along and say, “Hey man, let me share a screen.” Because the Chop Shop meeting was 90 minutes once a month, in the interim, people started to create offline connections on the phone. We also started texting each other to stay in touch and to share a quick idea or good news.

CL: At what point did you decide to mount an exhibition and introduce yourselves to the public, beyond the Chop?

SC: Around 2022, I talked with Roy and said, “You know, my opinion is that if something’s not growing, it’s dying, so what is the next iteration of us?” We had been doing this for a couple of years, and it was going well. There had been buzz in the meetings about how it would be great if we showed together. Specifically, we were beginning to see how the conversations in the Chop Shop were affecting our work.

RC: From the conception of the exhibition to talking to arts administrators, curators, museum directors, and other professional partners, the reactions were fascinating, but there was a lot of interest in the sensationalism of the dialogue, and sharing that was not our intention.

SC: For Roy and I as curators, what we didn’t want was to appear like we were just trying to get seen.

RC: It was so important for us to know what we wanted and how we wanted to be seen, because if we didn’t, there were so many people willing to tell us what we needed to look like and how we needed to respond. With that group clarity, it really helped us put together the exhibition.

SC: The only caveat that Roy and I made was that works were made during the window of the Chop Shop, starting in 2020, because the goal of a visual representation of our work is to show how our gathering in the Chop Shop affected our respective work and studio practice.

CL: From this one guideline, how did you select the works in the show? Can you take us into the curatorial thought process on the selection and the conversation that emerges between the works?

RC: Everybody put the work that they wanted to submit into a directory, and Steve and I were sitting side by side, having a conversation about each piece;. We knew the work, and what the artists were thinking about it.

I would say the work in the show unfolds like the chapters of a book that speaks to being a Black man in America at this time. There are sections and chapters; these are all the things that we bring to the table within our meetings, when one of us would say, “I need to check in with you on this…” In the Chop Shop we’re checking in with each other, and now, through the show, we’re checking in with the public.

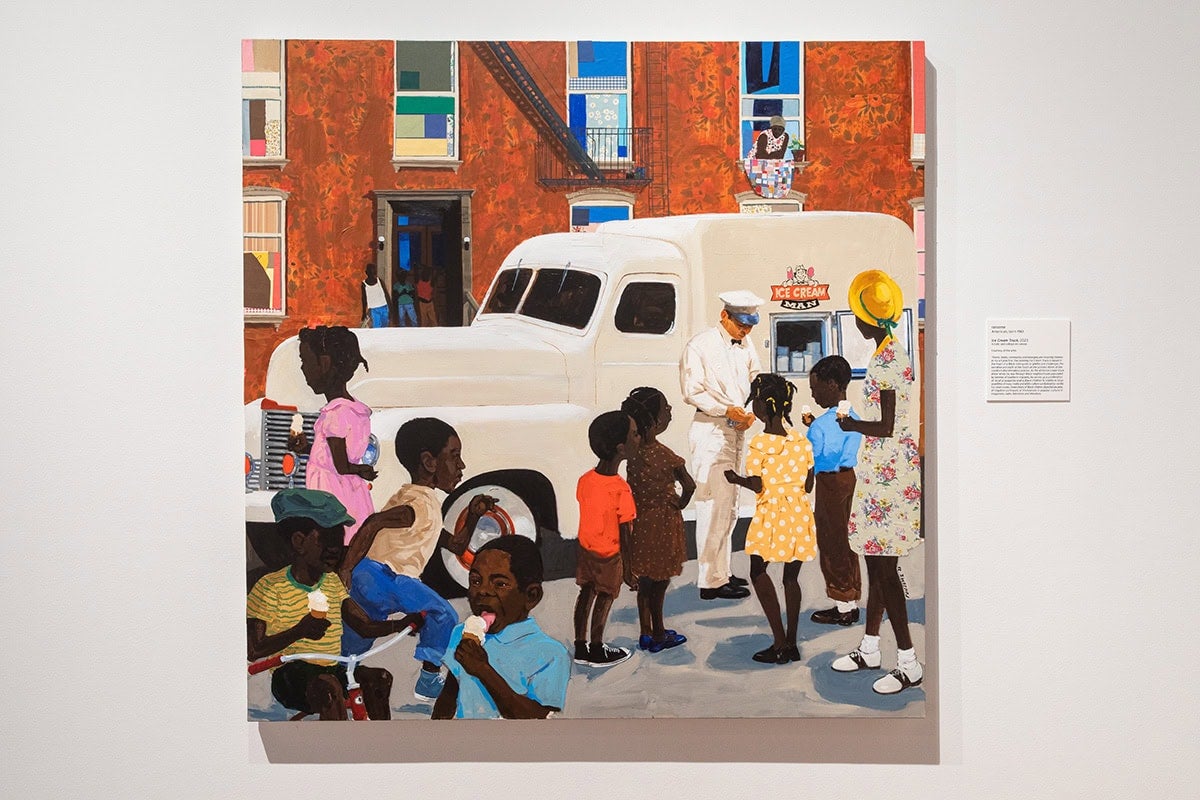

CL: I appreciate the chapter reference there because pieces in the show set the tone for me. Clarence Heyward’s Looking for Terry (2024), coupled with ransom’s Ice Cream Truck (2022), address externalized perceptions of Blackness. Then I see another conversation taking place among Ja Ja Swinton’s portraits and Jalen Jackson’s self-portraits that beautifully render internal, emotional struggles. I also see a world-making element among works by Tyrone Geter, Bryan Wilson, and Percy King. There were distinct artistic conversations taking place.

In your opinion, what is the takeaway that you want visitors to experience with this show?

RC: You could probably ask every member of the group, and they would all have a different response, but I think Steve could probably give you the best overall reason for the show’s purpose.

SC: Everything is an extension of our thought processes. At the end of the day, I am concerned with how the Black community treats each other. We don’t always see eye to eye, which is fine, but if you can remove that smoke screen, my hope is that we could align. I want us to simply talk to each other.

I think about Jalen Jackson’s boxing series. In it, he’s going through the emotions of an altercation he had in Middlesex, North Carolina. Each section of the triptych is a different emotion. During the opening, he mentioned that someone walked up to him, pointed to one of the panels, and said, “That one right there, I feel that every day. I feel like that at the job every day.” People are sharing that common thread. It’s been interesting to see reactions to the show within the Black community.

I also think that part of it is understanding the “art world.” We’re trying to be in the art world, but not of the art world. Of course, we want to make and show our work, but this idea of hoarding information and gatekeeping is not part of it. Within the art world, there are expectations based on stereotypes, that makes for a weird mix between what the art world is supposed to be and what black men are supposed to be. I feel like this group defies both of them.