TYGAPAW is a Jamaican-born techno artist currently residing in New York. Their music chronicles personal history (such as their immigration from Mandeville, Jamaica, to Brooklyn, NY) and communal relations within the Black electronic music diaspora. When DJing in white-dominant spaces, their art manifests as sonic interventions that question, subvert, and overcome the ways colonialism manifests in the club (e.g. the exclusion of BIPOC and queer people from venues, the tokenization of Black queer DJs, and the erasure of Black musicians despite their contributions to the electronic music genre).

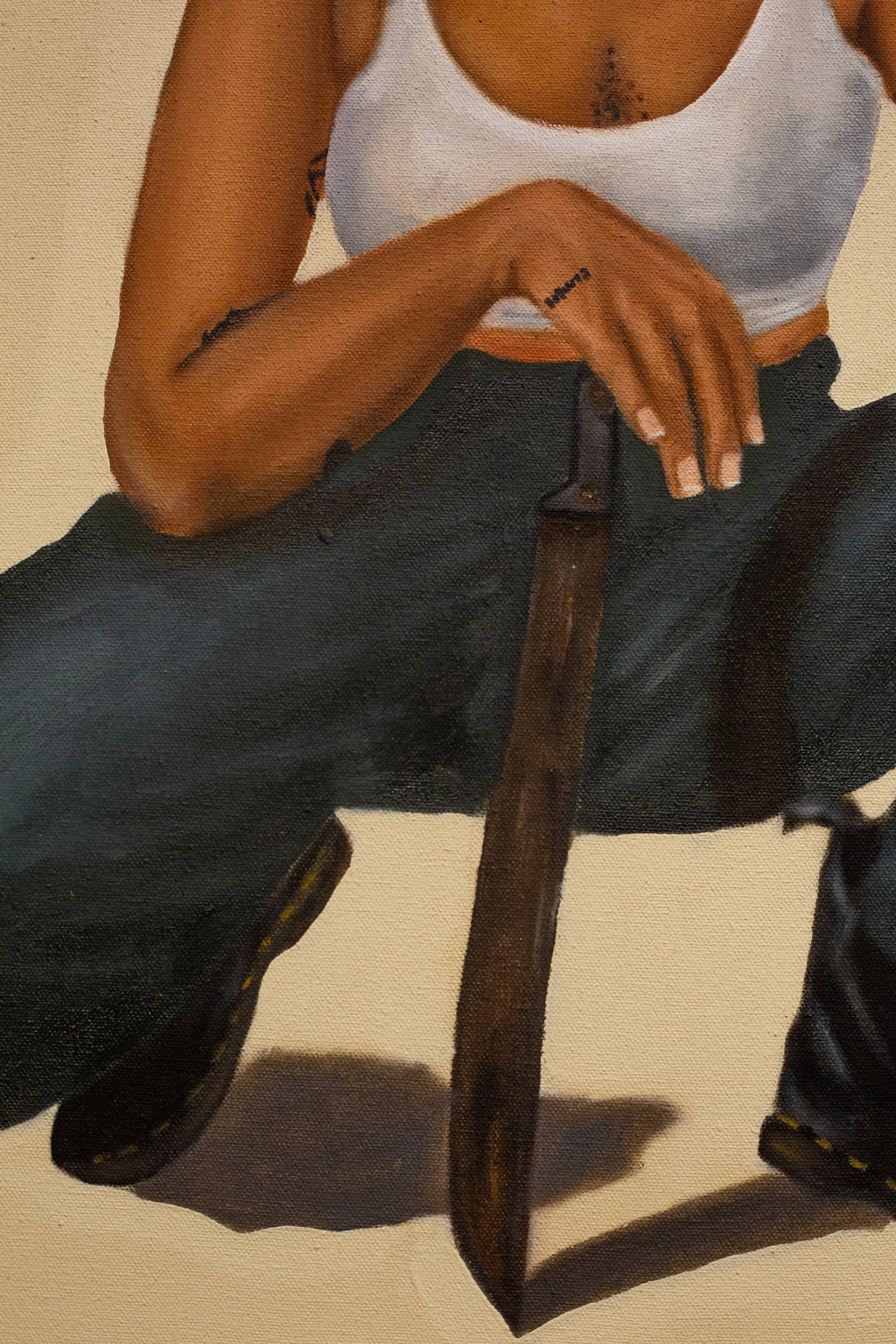

In July 2024 as a participating artist in BOFFO Performance Festival Fire Island, TYGAPAW performed a techno-opera titled Duppy Know Who Fi Frighten in the Fire Island Pines, a vacation town which attracts affluent white cisgender gay men. The glamorous mansion where TYGAPAW performed was a charged venue where capital, clout, and queerness collided. The work’s title was a reaction to these circumstances: Duppy Know Who Fi Frighten is based on a Jamaican proverb which the artist interpreted to mean “those who exploit know exactly who to target and who not to try.” TYGAPAW unleashed an auditory confrontation on festival-goers where they used synthesizers, pounding drum machines, and a wailing electric guitar to create a destabilizing techno soundscape. A roaming dancer in an all-black Duppy costume teased and taunted audience members. TYGAPAW channelled their personal experience of Fire Island as a Black trans-masculine person into the public sphere. Through Duppy Know Who Fi Frighten, the artist called into question whether the LGBTQ+ haven where they debuted this performance was as inclusive and liberating as some claim it to be.

Lucas Ondak: I would like to begin with the figure of the duppy in your work. In the 2024 BOFFO Performance Festival, you evoked the duppy through the sonic interventions you were creating in the performance venue (a vacation home transformed to mimic the club). What about the duppy was inspiring to you, why did you conjure it into being in this performance?

TYGAPAW: It’s definitely tied to my ancestry as a Jamaican; being born there and growing up there. The island possesses quite a mystical and powerful energy and aura that is connected and tied to its history. I grew up with a lot of folklore. Even if I didn’t understand it, I was intrigued by the visualization of frightening things. Rolling Calf is one of the stories I was told as a kid that was extremely scary because it’s this looming, monstrous figure with horns that lurks in the deepest abyss of darkness. To me, Rolling Calf is a story tied to slavery in the Caribbean. There’s also Annie Palmer, who murdered all of her husbands and now haunts the plantation she helped run. Duppies are a big aspect of Jamaican culture. The duppy represents acts of violence that no one has atoned for.

LO: In the performance, was the duppy an external manifestation that you noticed and brought attention to, or was it coming from within you?

TYGAPAW: I was the duppy. I am the duppy.

To me, you can either accept the duppy’s presence and all it represents, or you can resist it and be in constant conflict. I was mirroring how I felt on Fire Island. There, I embody elements that have been purposefully pushed out. I understand it was a necessary safe haven for gay men. But I question why the majority of the people there are white. As I transition, I’m very cis-passing. Still, it’s not a comfortable environment for me. So the disturbance is within me. I am the disturbed. I am an unsettled entity in a space that doesn’t accommodate my presence. It was up to the audience whether they accepted me or resisted me.

I think so much of Fire Island is that intense noticing of who’s not there, especially because of the beauty. That’s another Jamaica reference point: the land possesses an abundance of beauty, but who is entitled to it? Who gets to enjoy paradise?

Sometimes I wonder if the duppy stories are just a challenge to the status quo or the established narrative of a place. I come from an island that’s predominantly Black, but the people struggle to make ends meet because the government prioritizes whiteness through colonial infrastructures. Then, I’m on another island, which is supposed to be a utopia for people from marginalized groups, and all I see is white, cis gay men occupying the space of “paradise.”

Human history is so horrid, horrific things have been done to my ancestors. Being born Jamaican, being raised as a Jamaican, I understand that people view us in a certain framework. They expect us to be powerful athletes and profound songwriters and singers. Maybe being an immigrant, how I honor my ancestors in these spaces is to present work that brings attention to my history, histories of the Caribbean, and of the African diaspora. I was using the duppy as an entity of exploration and interrogation.

LO: On that topic, you’ve spent over a decade amplifying Black musicians and Black music history, and highlighting Black artists’ contributions to electronic music. You’ve resisted the erasure of real labor and real history. Could you talk about what fuels your advocacy and your commitment to the amplification of the Black Caribbean diasporic relationship to electronic music?

TYGAPAW: Sometimes I just think it’s instinct. It’s instinctual for me to bring attention to suppression, because my work has been suppressed. My suppression started with the colonial history that I was indoctrinated into. Going to high school in Jamaica—and, mind you, I went to all girls high school in Jamaica—I was conditioned to believe that there are roles assigned to me in society. There were very limited possibilities for me to go outside of that. But what’s true about Jamaican energy and ancestry is that we are rebels! It is literally in our blood. We have a history of resistance against colonial tyranny. That’s what revolutionized me: the histories I was taught were inaccurate, blatantly racist, and framed us as docile. We were fed lies to keep us subdued.

Electronic being a white-washed genre of music doesn’t sit well with me. I had a desire to see more people that look like me, that have the influences that I have. My work is always about experimentation and exploration of the truth. That pursuit of the truth led me to techno. It led me to make connections to dub music and Lee “Scratch” Perry and the invention of reggae. Perry’s work influenced whole genres within electronic music that are tied to Jamaica. Then I learned more about hip hop (Jamaicans created that genre as well). I followed The Prodigy, and it took me to Detroit and all the pioneers of techno. The false histories that I was taught in school and the lies our governments tell were debunked through the avenue of music. I’ve done my due diligence to go and reclaim my histories, to realize that I’m right where I’m supposed to be.

LO: Ghosts and duppies are messengers from the other side, or the eruption of obscured stories. I’m finding myself drawn to the phrase, “don’t shoot the messenger.” Some people view your work as difficult or confrontational, but all you’re doing is noticing injustice and bringing attention to it through your artistry.

TYGAPAW: When we look to history, it also creates mixed reactions. I think that that’s where the confrontation is. I get a kick out of situations when a white audience wants me (a Black artist) to present work that makes them feel comfortable. What I am doing is decolonizing electronic music—decolonizing techno—it’s work that is disruptive. I am being disruptive to the status quo.

World-building is a big part of my practice. I improvise quite a lot with musical instruments, synthesizers, and drum machines, and it’s like a conjuring or a seance. I create an atmosphere with sound, distortion, and heavy electronic beats and percussion. I can put you in a trance-like state that becomes the access point to the past, to the spirits, and to join in a ceremonial sort of practice.

I am the disturbed. I am an unsettled entity in a space that doesn’t accommodate my presence. It was up to the audience whether they accepted me or resisted me.

In Duppy Know Who Fi Frighten, I was trying to portray the highly spiritual work that we do as artists, and how that work can be lost if the audience doesn’t align with what it is that you’re trying to portray. That was a bit of the experiment within the performance; there were disruptive elements, but there was harmony as well. The intensity of my performances can create an overwhelming experience. These sounds are representations of the cries and the battle calls of my people.

LO: You’ve worked for many years to uplift your community and highlight Black music history. You’re a trailblazing musician, yet you face censorship, exclusion, and a lack of accessibility to a consistent livable wage. What needs to change to ensure that the Black creatives who build the nightlife and music scenes so many people benefit from have access to the safety and stability they need to continue their vital cultural work?

TYGAPAW: Yeah, such an important question, and I never know how to approach it. I’m Black, queer, and trans. It’s interesting, I had a lot of opportunities before transitioning, but as soon as I started to pass as a cis man, those opportunities stopped coming in.

What we’re seeing on a global stage is that the billionaires are unhinged. They’re letting the world implode. There’s an abundance of money, and then there’s multiple genocides happening at once, there’s famine, there are climate-change-induced natural disasters. A combination of horrific things are happening at once that are straining the majority population.

All I want to do is have the resources available to me to make some change and to continue the work that I do. However, I am financially restricted. I’m a highly skilled DJ, producer, curator, nightlife worker, and visual artist with a degree from a prestigious art school, but opportunities for everyone are dwindling. I’m putting out another album, but the budget is tight. I don’t have the financial wherewithal at this moment to produce my work. So my work gets suppressed.

LO: Your individual situation is emblematic of wider actions by large conglomerates of people who are invested in the systematic silencing of artists. The Israel-aligned equity firm KKR is acquiring music festivals and venues like Boiler Room, which are cultural scenes where artists like you rely on gigs to make your money to survive. Artists are being pushed to their breaking point: by taking a principled stance and fighting systems of oppression, you lose visibility, money, and opportunities. The alternative option is to capitulate to these powerful entities and compromise your vision and your integrity.

TYGAPAW: And that’s one thing I’m not ever compromising on. That’s another big aspect of ancestral power where I come from. Look at Jamaican artists. Nah, we’re not regular. We know a little bit about resistance. I won’t submit. I’ll find a way. My strength and my work comes from building community. For the past three years, community has been my savior in New York, which is in contrast to the capitalist society that is being forced onto us.

You can practice socialism in your own personal life. That’s what I do. When I can only afford one meal a day, my friends make sure I’m fed and healthy. I think that people get overwhelmed at the task of fighting fascism, but it’s small things: it’s giving emotional support to others, it’s talking to your neighbor, it’s inviting your friend over for dinner. As humans, we need each other. That is always the foundation of my work.