Houston-born artist and environmental advocate Ayanna Jolivet Mccloud understands what it means to advance change. Her minimal, abstract paintings, site-specific installations and performances embody her desire to reconnect people of the African diaspora to the environment. In addition to art making, Mccloud is the Executive Director of Bayou City Waterkeeper, a non-profit that fights tirelessly against water injustice in Houston. A year-long residency and recent solo exhibition entitled New Suns at Lawndale Art Center brought new clarity to her interrogations. The exhibition explored the cosmologies within West African textiles, migratory bird patterns, and the unacknowledged presence of Black people within histories of land and water. In this conversation, we discuss her artist-entrepreneur lineage, the aesthetic possibilities of restraint and why policymaking should be reframed as a creative act.

This interview was edited for length and clarity.

Amarie Gipson: You’re a native Houstonian and fourth-generation artist; that’s an important legacy. Who are the people in your life that made way for your work as an artist?

Ayanna Jolivet Mccloud: In recent years, I’ve reclaimed being a fourth-generation artist; I’ve not always said that, but it’s important to name it as part of my practice and history. I come from a lineage of artist-entrepreneurs. Most people in Houston know my father. He is a sign painter but also a fine artist. There’s a blurring of fine art, commercial art, and public art because he has done murals, but he’s also had exhibitions in the Museum of Fine Arts, Houston, and performed at Lawndale and Diverse Works back in the day. My grandfather is also an artist-entrepreneur and that’s where my father learned that model. They’ve always worked for themselves. My great-grandmother was an artist, too. She was working more in the craft tradition and from a gendered perspective, there were limits to being an artist at that time. She was a mom to multiple children, so the fact that she was able to make space for creativity is powerful.

AG: Most artists that I know have left their hometown at some point, and while I’ve usually rejected this notion that leaving the South is vital for developing your practice, I do understand the benefits. Can you share more about your personal and artistic migration journey?

AJM: Leaving Houston opened my eyes in terms of diaspora. I see this larger constellation and expansiveness that I’ve created in my practice by leaving my home, going to these other places and learning about this larger sphere within which I place my creativity. I was thinking about African-American identity and activism within a larger context. Because of the imperialism of the continental United States, African Americans are cut off from our histories and connections to the larger Americas. Chicago introduced new ways of thinking about art. The history of activism and social movements, you see that collectivity seeping through in artist spaces. I’ve been super inspired by the Caribbean, thinking about mysticism and ritual, magic, and dreaming.

AG: What made you return to Houston after nearly a decade of being away?

AJM: I didn’t think I was going to come back to Houston, but I could never really find what home was. I learned that home is internal and that I was creating a home in these different places. I felt a pull to come back and I felt so rooted when I did. Growing up in South Park, South Union, Missouri City, I resonated with green, unpolished patches of land. I yearned for those things. I was piecemealing what Houston was for me. Houston was space. Houston was nature. Houston was rural but urban, too. Houston was a rich culture that I had just neglected.

AG: You made a lot of noise when you returned to the city, opening and running your own space for artists and diving deep into arts leadership. Eventually, you pivoted out of the arts and into more direct environmental advocacy roles. I admire the overlapping threads between the presence of the environment in your art and the very real environmental issues you’re working to combat through Bayou City Waterkeeper. How do you situate these two different approaches to making a change?

AJM: Well, I feel seen and it’s nice because I am in a lot of different spaces. I’m an artist first, although I don’t know if people have always seen me as an artist because I am an artist-activist and I have this artist-entrepreneurial background. This is the first year in a long time that I’m making more space for my visual art. When it comes to environmental advocacy, it’s a lot of work. I’m also a single mom. My work is quite physical and laborious. So, I try to be mindful of pacing. What I’ve learned from advocacy is that it’s a powerful thing. One thing that I have done is make a distinction. I push back on “social practice” work; I’m not a social practice artist. I make art about different things. Sometimes, I do paintings that are quite abstract. I do site-specific installations, often interrogating history and then there’s my advocacy. That is separate. I’m an artist leading advocacy, but I’m not trying to converge those worlds and that boundary is really important to me. I get frustrated with the pseudo-advocacy in the art world because it’s sometimes too poetic.

AG: Right, because are these things happening as a short-term performance of a certain politic, or are we genuinely striving to affect radical and long-term change?

AJM: And it becomes very self-serving and incestuous. Part of my approach in this work is to learn. When I took this job, I checked all the boxes except for policy. I’m not a lawyer. I didn’t go to school for policy, but as an artist, I belong in this space. And the people who hired me saw that we needed a new approach. So, I see that my being an artist in this space is a way to reframe policy as a creative act. Policy has been used against my people, my family and so much of our communities. How can we have a voice in building policy and writing it? It needs to be dismantled and understood as a creative act.

“Houston is a water city, we are the Bayou City. Let’s reclaim that, forget the energy city. We know that we are the petrochemical capital and we’re fighting that. What does it mean to reconnect to our waterways and to reclaim that while we’re fighting these injustices?”

AG: I love what you’ve said about policymaking being a creative act, or at least reframing it as such to make space for new voices to enter in an advance change. What drew me to your work is your essay, “Water is A Point of Entry to Celebrate Juneteenth,” in which you connected Juneteenth and Houston’s water-centric origins to the city’s current climate collapse. What inspired you to write this piece?

AJM: The writing that I did around Juneteenth was a narrative change. Black people are the most impacted by water injustices. When you look at the pollution, the stronger violations are in Black communities. Where is the untreated sewage going? Where do we see more flooding? It’s in Black neighborhoods. We have to talk about the violations, the violence, the death, the loss that we continue to experience. These neighborhoods that experience water quality and quantity issues have compounded injustices. So we’ve got to fight those, but they also have beautiful leaders, rich histories, cultures, and ecologies that exist there. Our ecology might not look the same as a white, wealthier neighborhood. Our parks are not the same, but we still have rich spaces. And so, that has been my work, building up the capacity around policy work and an intersectional approach to water work that involves different disciplines, is highly collaborative, and reclaims the narrative.

Houston is a water city, we are the Bayou City. Let’s reclaim that, forget the energy city. We know that we are the petrochemical capital and we’re fighting that. What does it mean to reconnect to our waterways and to reclaim that while we’re fighting these injustices?

AG: Your exhibit, New Suns, deepens this connection between the water, the land, and the stars. What is the sort of celestial calling that inspired this body of work? I’m fascinated with the surface of the paintings in the show and the way you’re playing with space.

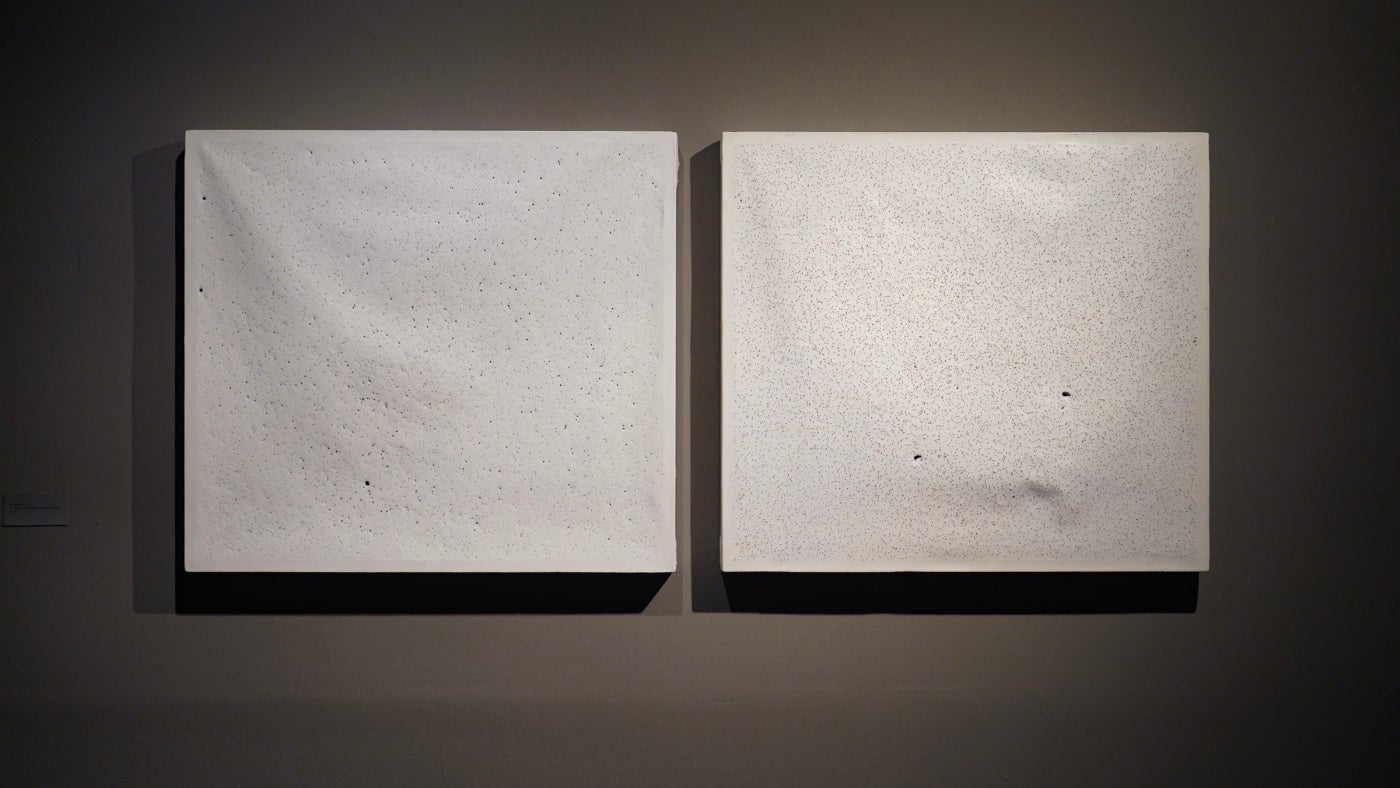

AJM: This [exhibition] has been a catalyst for me. Playing around with these connections to geography, nature and abstraction is a throughline in all of this work. The process might be dense, but I like sparseness and restraint from an aesthetic perspective because it allows people to insert themselves into these works. The work is quite internal. The process around the paintings is laborious: I paint the canvas, sand it, then gesso it, and sand it repeatedly until it becomes waxy. And at that point, I puncture it. It’s about internal space, about signaling to the space behind the canvas, the space that you don’t see. And visually, when you see all these punctures after this very in-depth process, it becomes cosmic. A lot of this work is about uncovering these cosmologies and geographies, this more literal space right in front of us.

AG: The larger star paintings cast shadows on the gallery wall that reminded me of the crescent shadows that appear on the ground during a solar eclipse. The ambient lighting in the gallery punctuated this sense of solarity. There are also a number of photos of landscapes connected to specific Black people, like Sandra Bland, Eric Gardner and Ahmaud Arbery.

AJM: I’m trying to converge these different bodies of work. I needed it to have something literal, to talk about Black people in relation to the environment in a direct way. There are these imagined spaces that Black people who were killed by the police could have touched or encountered, ones that have very specific connections to the land. That was an opportunity to say, “I see you.” We exist in these different histories. It just takes a little imagination to uncover these connections.