Aineki Traverso’s studio at the Atlanta Contemporary’s Studio Artist Program is a homey, brick-walled space packed with paintings in process. She tells me she just received news that she won a 2024 Atlanta Artadia Award. On her laptop, she virtually tours me through her long narrow canvasses and various tondos, stepping around carts of paints, brushes, and pastels. Immediacy rises from each work, dynamic sprawls of bodies emerging from what could be mud or dreams or the Heavens or a primordial soup of regeneration. Hands and knees extend then sink from view. Aineki points to two panels dominated by warm yellows, mauves, and forest green, recently shown installed into a corner at the Temporary Arts Center’s …an Atlanta Biennial…, and begins narration.

Burnaway is excited to present Aineki Traverso’s work at the New Art Dealer’s Alliance fair in Miami, on December 3-7, 2024, at Ice Palace Studios.

This interview was edited for length and clarity.

Aineki Traverso: I love this lady smoking, but she doesn’t have a cigarette or a face. She has other faces layered on top of her own. I started making two landscapes with unusually long aspect ratios of three by six feet, thinking about a diptych, but when I started adding bodies to the canvases, I realized the paintings belong in a corner, with the two panels touching. Where the edges meet, the main figure continues into the next canvas, or plane. I’ve been thinking about the way people interact with an object and space in relation to other people when viewing a painting. The corner placement makes for an intimate viewing experience, and can create a place of empathy because you’re thinking about your physical self and physical selves around you.

Aineki points to a section of the painting.

Aineki: Here a breast appeared, so I emphasized it, then in the corner I referenced Alexandre Cabanel’s “The Fallen Angel,” from Dante. I paint him often. His eyes hold a strange expression and subtle tear. Eyes are a shape I’ve always been interested in. I went through a period working to reduce eyes into minimal lines. I’d paint one with three lines or through a reductive method like scraping paint off. It’s an interest in their form, their complexity.

Jane Marchant: Do all your paintings rise on their own, or do you approach them with a specific thought, memory, or emotion? How much is intentional?

Aineki: I have some paintings where I choose one reference image and have the intention of painting that directly. My small works on paper are not just studies, they’re complete paintings, and creating them is an intimate experience similar to the way being on the ground as a child is an intimate examination of small things. The first thing I do when I enter my studio is resolve a small work on paper, then go into a bigger painting. I move between paintings and work on many surfaces at once, and there’s a throughline broken up by when I return to another work on paper. Sometimes at the end of my studio session, I’ll do another one. It’s not inception, but it is resolution because I finish them. I never go back to them.

Most of the time, I paint from my image archive. I’ll flip through a group of images speaking to me and land on one I’m most interested in, whether it’s for the composition, palette, or figures. I don’t do underpaintings, that’s not my style. Sometimes I start sketching with pastels, beginning with some kind of landscape.

I ditch my reference image quickly to begin layering, and that’s where the intuitive part comes in. I’ll start looking at other images in my archive and find one figure fits here or add from memory. I’ll be painting the tree from a photo then see and paint a face. By referencing photographs, I’m creating a landscape out of these condensed pieces of time. I’ll sit in a dark room with a projector, placing images onto the painting to figure out compositions, zoom into a photo, and see how the information synthesizes on the surface. That’s when the planes and bodies start combining and doing something interesting.

Jane: When you’re in the dark with a projector, does color matter, or are you more interested in the physical composition and layout?

Aineki: If I’m projecting onto a painting, color disappears. I mark where the figure begins and ends, then turn the lights back on so I’m not painting in the dark. I mostly spend time looking through photos on it.

Jane: For someone unfamiliar with your image archive, how do you define it?

Aineki: It consists of childhood photos, photographs family members have taken of places and objects, and photographs my mom took when she was younger. For her, photography was something she could do when she wasn’t able to paint. She has thousands of photos. On top of inherited material, my archive contains photos I’ve taken and photos saved from the internet and Google Street View. I try to take photos every day on my phone. If I want to paint a lady sitting in a chair, I could do it from memory, but with a photograph, I get more accurate information. I’m not consuming an image. Once you paint someone, the subject changes; there’s a transformation, the painting becomes a vessel rather than a person. A photograph is about learning, looking at information that’s been organized in a particular way, and reorganizing—transferring it with paint is my practice.

Jane: As you consider your paintings in relation to humans and space, how does your work transform?

Aineki: I’ve been experimenting with what I call thought paintings. For example, I came up with one idea about scale and magnification as I scraped my palette table, which had so much buildup helictites formed. I peeled layers of paint chips and looked at them though a TV rock, a mineral-like magnifying glass. Although it doesn’t change the scale, it made the paint look almost digital, as if on a screen. I thought, what if I had a show with paint chips and this TV rock for viewing? What if I had a magnifying glass? What if I change the scale and use a telescope? But then the painting would have to be really far away, and really big.

Once you paint someone, the subject changes; there’s a transformation, the painting becomes a vessel rather than a person.

Idea Capital’s Susan Antinori Visual Artist Grant proposal was due that night, and I thought, I’m going to apply. I ran home and wrote the proposal, and I ended up getting it. Later, I was commissioned to create the work for the Goat Farm’s festival, SITE, which took place during Atlanta Art Week. I modified the project to make it a site-specific installation at their old manufacturing complex, which is an arts space of partially-renovated buildings and ruins across 12 acres.

Jane: How did that site installation change the piece?

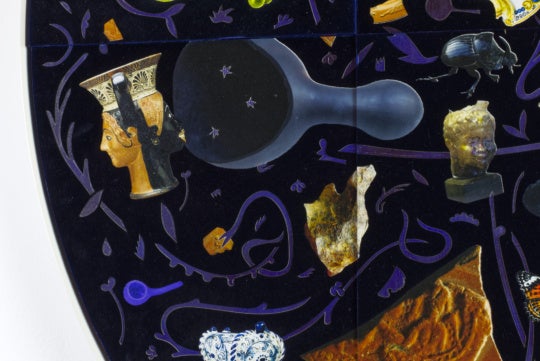

Aineki: My original proposal was for a viewfinder inside a building looking across the street, through a window at a painting. I struggled finding a place because it required two buildings, a hundred feet apart. My installation site was a huge abandoned warehouse with a hole in its roof, a wall of gridded, broken windows, and a tree growing in its center. The location accommodated the focal distance and the huge tondo I was working with—it has an eight-foot diameter and weighs about 120 pounds. The viewfinder was pointed at the painting. I named the installation, The Middle Distance.

Thousands of people RSVP’d to the event, and seeing people interact with the piece shifted something for me. My piece was at the end of the grounds and people started lining up because it’s a one-person activity. It was dark at the viewfinder so the brightest thing was the painting. People lined up, rather silently, sometimes feeling pressured not to take too long. No one told them to, it just happened. I hadn’t thought about the social aspect, of how people would interact with each other or try to take a photo of the installation—you can’t, it’s impossible to photograph.

A lot of people thought it was a projection and I said, no, it’s a painting. They were like, oh, you projected the painting? I had to explain, no, it’s oil on canvas. It’s an object. A light’s on it. But so many people, looking through the lens and having this solitary experience, perceived it as digital or projected. Most people hang out on their phones, which is a dissociated act. You’re looking through a lens, alone. It’s such an unnatural thing to look through a lens or see your reflection. The only reflections in nature are on water, but even then only when it’s perfectly still.

Jane: That’s how Narcissus died.

Aineki: Right.

Jane: That would make an interesting installation, looking through a viewfinder at Narcissus dying, looking at his reflection.

Aineki: Maybe I’ll put Narcissus in a painting.

Jane: What do you think of artificial intelligence and the idea of the lens?

Aineki: AI in image-making is bizarre. Painting serves as a way to resolve ideas or images or concepts. It’s a path to resolution. AI replaces that. If I want to figure out how to paint a portrait of a lady sitting in a chair, I have to do the work of making the study and figuring out proportions, palette, and lighting within the painting, tools, and material. With AI, if you type in a prompt like “lady sitting in a chair,” it will do that work, which is scary to me because it’s automatic. I’m interested in using painting to think through a world that exists with nature and technology, and people interacting with objects and space, in relation to other people. If taken outside of the gallery or art space, can a work encourage a moment of empathy between one physical self and other physical selves?

Aineki takes her laptop over to the tondo leaning against her studio wall. A face appears within a tree. Figures surface from a swamp, and one woman’s hand drifts visible underwater, as if the viewing plane has been sliced. Another woman emerges from the green, with blood-red eyes and ears as her face morphs into the water.

I ask, Is she evil or hurt?

Aineki does not yet know.

Burnaway is excited to announce our solo presentation of work by Atlanta-based artist, Aineki Traverso at NADA Miami, 2024! Come see us Tuesday, December 3rd through Saturday, December 7th, 2024 at Ice Palace Studios, Miami.

Aineki Traverso (b. 1991) is a painter based in Atlanta and a current resident in the Studio Artist Program at Atlanta Contemporary. Her work has most recently been exhibited in spaces such as Swan Coach House Gallery, Johnson Lowe, and Whitespace Gallery. Aineki has attended residencies at R&F Handmade Paints, Vermont Studio Center, Hambidge Center for Creative Arts, and VCCA. She graduated from Sarah Lawrence College in 2013 with a concentration in film theory. She has received support from the Atlanta Artadia Grant (2024), Nexus Fund (2024), Idea Capital (2024), and the Forward Arts Foundation (2023). She runs a zine, Iterance, that aims to publish artist books using accessible arts writing to engage the discourse of painting.