In the wake of Krista Clark’s inclusion in the recently opened 2021 New Museum Triennial: Soft Water Hard Stone, MaDora Frey interviewed the Atlanta-based artist about her evolving practice.

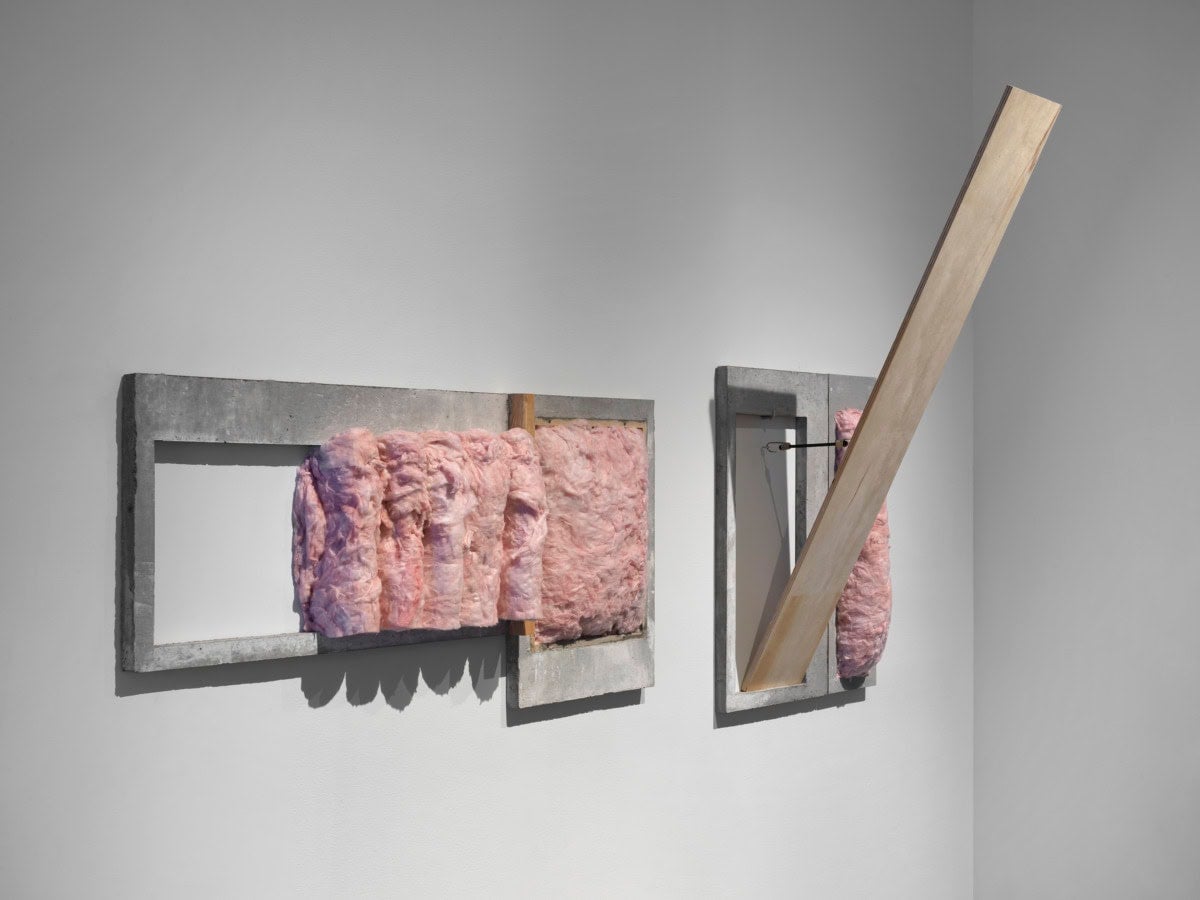

The physicality of Krista Clark’s sculptures appeal to the senses and occupy the mind. Crinkly tarps flutter over architectural skeletons of two-by-fours, poured concrete slabs still in their rectangular molds, a window casing rests against a half-built wall. Krista Clark riffs on the forms, materials, and gestures common to oversized, new construction. It’s the kind that sits starkly against established, historic homes in urban areas.

A second reading of the work leads us to her inquiry of the intense shift occurring in urban neighborhoods. What are the visual markers, who is forced to relocate because rents are too high, far away from family and friends who bought long ago, and who are the people moving into these freshly minted structures?

Clark’s minimalistic work adds breadth to the range of art coming out of the South. For years, Black artists working outside of figuration operated on the sidelines, and were predominately men. “Unbound,” a recent exhibition at the Zuckerman Museum, highlighted such artists. In her curatorial essay, Nzinga Simmons writes that working in abstraction for artists of African descent allows them to eschew “the burdens of representation, politics, and identities inherent to figurative or representational work.” Of the seven artists in the show, Krista Clark was the sole female contingent.

The day I visit her Westview studio in an old church, it’s predominantly empty but holds the residual energy of a space in constant flux. Clark has just completed and shipped out her work for the New Museum’s Triennial, Soft Water Hard Stone and is one of only two artists selected from Atlanta. As she tells me of her recent purchase of a cement mixer to speed her pouring process, thanks to an award from MOCA GA, I easily imagine it churning away in the center of the room.

MaDora Frey: Tell me about your former art life as a printmaker and how it now informs your work.

Krista Clark: I liked lithography the most. Even though there is mediation between the gesture and the final work, the physical connection and directness of drawing on the stone was gratifying for me. You can make different versions of a drawing without it feeling too risky. It’s less committal since there isn’t just one single print. It doesn’t feel as precious. The multiple iterations of the same materials and forms also ties back into the content of my current work.

MF: Was there a specific moment you recall breaking away from traditional media and moving into sculpture? Must be liberating, working with all these different materials.

KC: For my thesis show, I incorporated tar paper into the work which was still very much about 2-dimensional space. After graduation was a really fruitful time in terms of expanding. I got to just be in the studio and play with materials, gradually introducing more and more into the work. I left behind the strategic approach I had with my drawing and now work more improvisational. Also, because I don’t have a background in architecture or sculpture it’s me, just finding my way through with the material. And now, since the installations began, my drawings too have become more impromptu.

And absolutely liberating. Continuously. Just because there’s so much more possibility that’s informing how I approach my paper works or drawings. That continues to be exciting. There are no boundaries that I give myself. I guess coming from a drawing, printmaking background, it’s useful to know those rules and not feel worried or think “Okay, this is what the hell it has to be”.

MF: So, it’s very much about the work as a thing unto itself? As Frank Stella said, “What you see is what you see”.

KC: Yes, it’s not about embellishing or creating an illusion. What I try to do, depending on what the project is, is not have that “design” mind come in. With the show at MOCA, while working with poured concrete, for instance, I reasoned that the molds that were shown wouldn’t have this clean polished aesthetic, because that’s not their purpose.

MF: What contemporary artists resonate with you right now?

KC: I often come back to Gedi Sibony for his pointed but at the same time poetic use of material. I find his directness incredibly beautiful. Other artists, for similar reasons, Jennie C. Jones, Mateo Lopez, Hugh Hayden, Eva LeWitt, Gordon Hall…and I can’t stop looking at Jennifer Packer’s paintings. The psychological space she creates is impossible to resist.

MF: Did the context of the Triennial influence the way you approached the new work you made for the show?

KC: I think it opened up how I am working with concrete and made me think in terms of creating modular pieces. I can now easily move the pieces around and re-combine them with other works. I like this because it mimics the way I make my works on paper and is in line with how I approach other materials in my process.

The curators, Margot Norton and Jamillah James, were extremely thoughtful in their curation and selection of artists. Rather than beginning the process with a preconceived idea or vision, they looked for patterns amongst the artists they visited and really allowed that to dictate the theme and subthemes of the triennial. Because of that, I didn’t feel I needed to bend in a direction that was unfamiliar with my work.

The 2021 New Museum Triennial Soft Water Hard Stone is on view thru January 23, 2022.